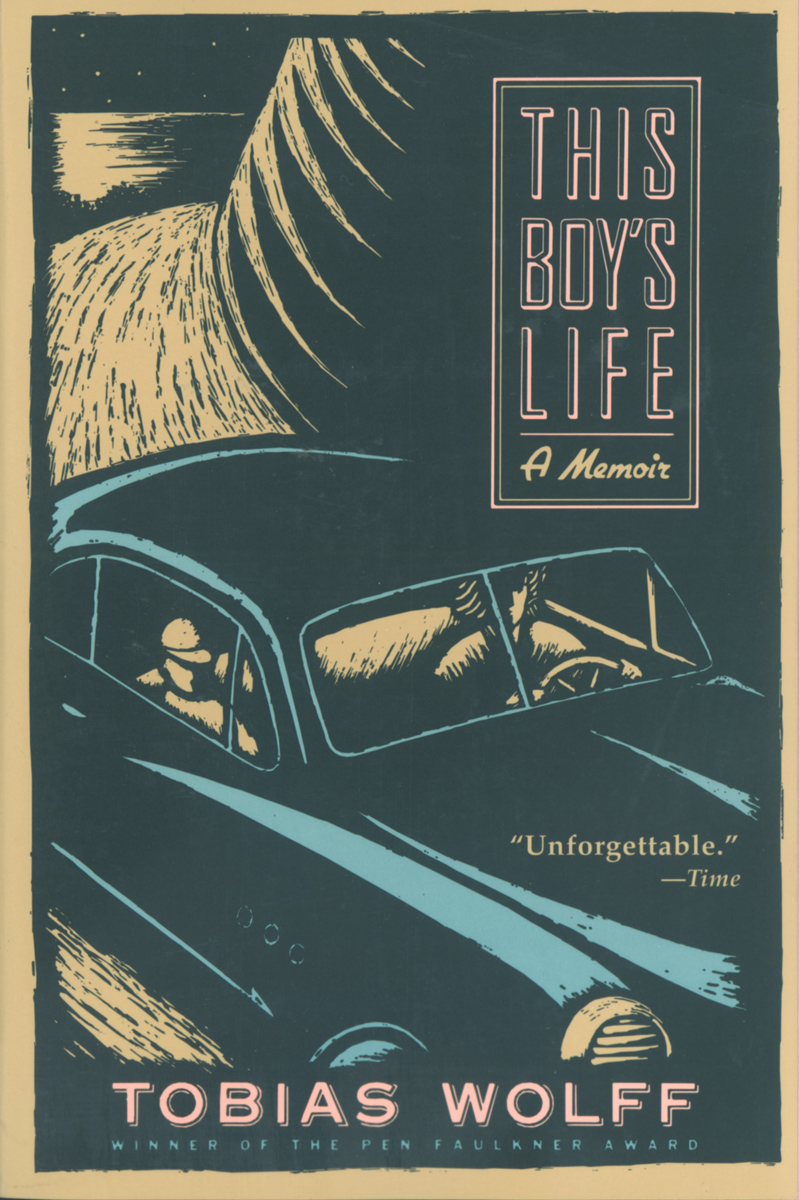

This Boy's Life

Overview

Winner of a 2014 National Medal of Arts from President Barack Obama, Tobias Wolff is a novelist, memoirist, short story writer, Vietnam veteran, Stanford professor, family man and a National Endowment for the Arts creative writing fellow. His memoir, This Boy's Life (Grove Press, 1989), tells the story of his early days in the 1950s—moving with his mother from Florida to Utah to Washington state—and his rough years as a young adult at the hands of an abusive stepfather in a small town north of Seattle. It was made into a 1993 film starring a young Leonardo DiCaprio. The Philadelphia Inquirer describes the memoir "as grim and eerie as Great Expectations, as surreal and cruel as The Painted Bird, as comic and transcendent as Huckleberry Finn." "So absolutely clear and hypnotic," says The New York Times, "that a reader wants to take it apart and find some simple way to describe why it works so beautifully." Says The Independent, "Tobias Wolff writes like a man winning his way towards truth."

"When we are green, still half-created, we believe that our dreams are rights, that the world is disposed to act in our best interests."

—from This Boy's Life

Introduction to the Book

"[This] extraordinary memoir is so beautifully written that we not only root for the kid Wolff remembers, but we also are moved by the universality of his experience." — San Francisco Chronicle

Tobias Wolff's memoir, This Boy's Life (Grove Press, 1989), is a story about a mother and son trying to survive in 1950s America. Separated from his father and brother and without good male role models, Wolff struggles with his identity and self-respect when his mother moves the two of them across the country. They eventually settle in northern Washington where Wolff finds himself in a battle of wills with a hostile stepfather. Wolff's various schemes—running away to Alaska, forging checks, and stealing cars—lead to an act of self-invention that releases him into a new world of possibility. "Wolff writes in language that is lyrical without embellishment, defines his characters with exact strokes and perfectly pitched voices, [and] creates suspense around ordinary events, locating the deep mystery within them" (The Los Angeles Times Book Review).

When Wolff is ten years old, his mother, Rosemary, decides to move them from Florida to Utah, caught up in the desire to strike it rich digging for uranium. When that doesn't work out, they move to Seattle where Wolff finds an outlet for his frustrations through shoplifting, drinking, breaking windows, and writing obscenities in public places. Rosemary, meanwhile, meets Dwight, a man from the town of Chinook, 70 miles north, who succeeds in persuading her to marry him. Wolff spends the rest of his childhood with his mother and Dwight in Chinook, enduring Dwight's petty meanness and cruel verbal and physical abuses. In an attempt to escape Dwight's relentless berating, Wolff joins the Boy Scouts, but Dwight makes himself an assistant scoutmaster. Wolff becomes friends with a boy in his school, Arthur Gayle, but Dwight encourages Wolff to fight Arthur, calling him a "sissy." The high school crowd Wolff eventually joins is far from upstanding. "I grew up in a world where violence was all too common—not deadly violence, so much, but beating, bullying, and threats—certainly in relations between boys, and between men, and often between men and women," Wolff told The Paris Review.

Wolff lives much of his adolescence in his imagination, dreaming up ways to escape his reality. He finally does escape by getting accepted to a prestigious school on the east coast based on fictitious claims that he was a top student, star athlete, and model citizen. The last time he sees Dwight is when Dwight follows Wolff and his mother to Washington, D.C. and tries to strangle his mother. He was "standing in a snowstorm, with policemen holding his arms," said Wolff. "My mother had bruises on her throat for weeks afterwards. They found a knife that he'd thrown into the hedge" (The Guardian). When This Boy's Life came out in 1989, Dwight was still alive, though very ill. "One of my stepsisters called me in a fury and said that her daughter had read aloud This Boy's Life to Dwight while he was lying in bed, and he was so hurt by it," said Wolff. "I think maybe she should have looked at it first" (The Guardian).

Wolff didn't set out to publish a memoir. He was more interested in recording memories "so that my children would know how I grew up," he says. "They were raised in an academic atmosphere, and my mother by that time was a very proper old lady" (The Guardian). "As I started getting these memories down, they took over," he said. "Writers wait for that moment when the material starts to carry them. It happens more rarely than one wants to think, and you're a fool if you don't give in to it when it does" (The Paris Review).

"Wolff writes in language that is lyrical without embellishment, defines his characters with exact strokes and perfectly pitched voices, [and] creates suspense around ordinary events, locating the deep mystery within them," writes The Los Angeles Times Book Review. This Boy's Life was made into a 1993 film of the same name directed by Michael Caton-Jones and starring a young Leonardo DiCaprio as Wolff, Robert De Niro as Dwight, and Ellen Barkin as Wolff's mother. It's a story that resonates in more than one medium. "We live by stories," Wolff told The Paris Review. "It's the principle by which we organize our experience and thus derive our sense of who we are."

- Begin the discussion by considering the book's epigraphs: “The first duty in life is to assume a pose. What the second is, no one has yet discovered.”—Oscar Wilde. “He who fears corruption fears life.”—Saul Alinsky. Why did the author choose these quotes? Do you think they fit the themes explored in This Boy's Life? Describe the primary pose assumed by each character. Is there tension between these poses and those of other “corrupt” ones that surface?

- Jack's tongue becomes so tied at his first confession that he finds his voice only by borrowing the sins of Sister James. Why is Jack unable to confess his real sins? The father and Sister James are satisfied, even proud of Jack, when he completes the ritual. Do you think Jack is absolved for his sins even though he lied? To the narrator, in the eyes of the church, is the act more important than the truth behind the confession?

- Extend the idea from the last question to the act of writing a memoir: In the introduction the author attests that he tried to “tell a truthful story.” Do you think the morals and themes of the memoir remain intact even if they don't always adhere to the facts?

- When Rosemary asks if Dwight and Jack are getting along, Jack lies: “I said we were. He was in the living room with me, painting some chairs, but I probably would have given the same answer if I'd been alone.” Why can't he tell his mother about Dwight? Do you think his reluctance stems from fear? What else might make Jack protect Dwight's early, nice-guy façade? Do you think this protective behavior is positive or negative?

- Alienation defined much of Jack's childhood, in part because of his fractured family. Once settled in Chinook, his mother, Rosemary, attempts to re-create a “real” family. Jack writes, “But our failure was ordained, because the real family we set out to imitate does not exist in nature.” Do you agree with this? Do you think the perfect family is a myth? What expectations does Jack have of his family?

- The memoir is set mostly in rural Washington, high in the forested mountains. The author uses the weather common to this area as a metaphor for Dwight's badgering: “I experienced it as more bad weather to get through, not biting, just close and dim and heavy.” How else does the stark Northwestern landscape enter and influence the narrative? Contrast the depiction of exterior spaces with that of the white interior one in which the family lives. What does Dwight's obsession with painting everything white, including the tree outside, suggest about his personality?

- The residual influence of fathers plays a prominent role in the story, hinging on brief glimpses of Rosemary's father, referred to as Daddy, and the late emergence of Jack's biological father from back East. Compare the influence of these fathers—one violent, the other irresponsible—on their children. How do Rosemary's and Jack's behaviors reveal the kind of interaction they had with their fathers? Which father do you think left a more permanent “mark” on his child?

- “But what I liked best about the Handbook was its voice, the bluff hail-fellow language by which it tried to make being a good boy seem adventurous, even romantic. The Scout spirit was traced to King Arthur's Round Table.” What does this passage reveal about the imaginative space in which Jack lives? Discuss how this relates to his ability, later in the story, to invent his own persona.

- When Jack is accused of scrawling obscene graffiti on the bathroom wall at school, we are introduced to the vice-principal and principal, men whose disciplinary approaches radically differ. Compare these two authority figures with the two father figures in Jack's life—Rosemary's first boyfriend, Roy, and her new husband, Dwight. Is there any correlation? About the principal, Jack writes, “He wore his weakness in a way that excited belligerence and cruelty.” How does this relate to Jack's concept of what a man should be? How is Jack's original impression of Dwight turned upside down?

- Pop culture references are used carefully in the text. We discover, for instance, that Jack and his friends watched The Mickey Mouse Club, and that he and his mother watched The Untouchables. What other pop culture references are used? To give the reader a sense of place and time, what, besides pop culture, does the author refer to? Did the story seem anchored in the 1950s or did it evince a sense of timelessness?

- Leaving Seattle, Jack and Chuck become giddy because, as Jack puts it, “We were rubes, after all, and for a rube the whole point of a trip to the city is the moment of leaving it.” More frequently, an intelligent, disaffected youth runs to the city to get away. Yet Jack doesn't dream of blending into the crowd of an urban center—his one serious plan of escape is to Alaska. Why is Jack's sense of freedom so connected to open spaces?

- Jack's botched attempt to run away to Alaska may be one of the more heart-wrenching episodes in the narrative. Why does Jack disregard the urging of his friend Arthur at the Gathering of the Tribes? Why do you think Jack is unable to carry out his plan? Discuss the conflict between Jack's desire for freedom and his desire to belong. Compare this incident to when Jack nearly gets caught writing a bad check at the corner drugstore. How does Jack regain his composure?

- After the boys get caught siphoning gasoline from the Welches, they blame it on drinking. “Mr. Bolger nodded, and I understood that this was in our favor, so great was his faith in the power of alcohol to transform a person.” Keeping Jack's encounters with his stepfather in mind, do you think the author's musing was intended as ironic? Should the boys be held less accountable for their actions when drinking? What about Dwight's actions?

- Guns are a constant presence in Jack's life. Trace the arc of guns throughout the memoir, beginning with Jack's initial exposure with Roy and ending with his stealing and selling the guns at the pawnshop in Seattle. Does Jack's attachment to guns affect his behavior? Who, if anyone, dissuades Jack from gun use? Do you think Jack displayed any transformation or development by getting rid of the stolen guns?

- When applying to prep schools, Jack writes all of his own letters of recommendation and transcripts. He justifies this by suggesting that only he knows the truth about himself. Do you think this assertion applies to everyone? When accepted at Hill, did you consider this a turning point in Jack's life?

- As a young child Jack plays a game in which he is an imaginary sniper firing at people who held an “absurd and innocent belief that they were safe.” As a teenager Jack goes to the Welches after his theft: “It had to make them feel small and alone, knowing this—that was the harm we had done. I understood some of this and felt the rest.” Discuss the significance of these two disclosures by the author.

This Boy's Life discussion questions provided courtesy of Grove Atlantic.