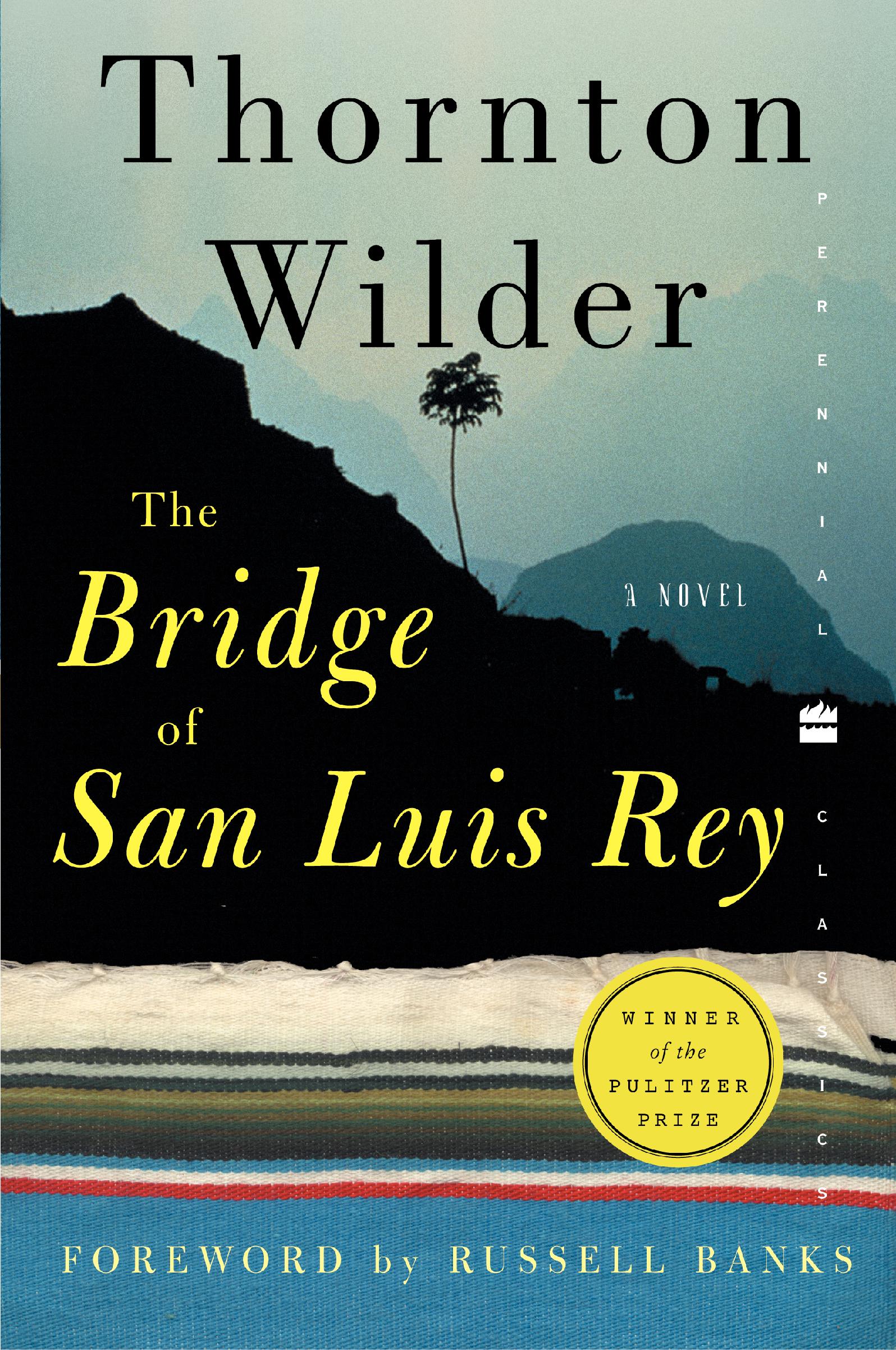

The Bridge of San Luis Rey

Overview

To know a book, you have only to read it closely. But to know a writer, one book is almost never enough. This is certainly true of Thornton Wilder. At first glance, his novel The Bridge of San Luis Rey and his play Our Town may appear to have little in common. One is about the search for meaning after a fatal bridge collapse in Peru, the other about life in a small New Hampshire town. Only after contemplating these timeless stories side by side do we begin to discover the signature they share: an appreciation for life’s preciousness in the shadow of eternity.

"It seems to me that my books are about: what is the worst thing that the world can do to you, and what are the last resources one has to oppose it." —letter to friend, 1928

Overview

To know a book, you have only to read it closely. But to know a writer, one book is almost never enough. This is certainly true of Thornton Wilder. At first glance, his novel The Bridge of San Luis Rey and his play Our Town may appear to have little in common. One is about the search for meaning after a fatal bridge collapse in Peru, the other about life in a small New Hampshire town. Only after contemplating these timeless stories side by side do we begin to discover the signature they share: an appreciation for life’s preciousness in the shadow of eternity.

Introduction to the Book

By Tappan Wilder

Thornton Wilder’s novel The Bridge of San Luis Rey (1927) and his stage drama Our Town (1938) have enjoyed enormous success since the moment they first appeared. Both won Pulitzer Prizes, and neither has ever been out of print. Because they have been widely read or performed abroad, this novel and play are not only American classics but classics of world literature as well. They are so well known, in fact, that we easily take them for granted. Whether you are rediscovering Wilder’s work or entering his world for the first time, you are joining thousands of his readers in exploring the fundamental meaning of human existence.

At first glance, these two stories may appear to be worlds apart. Our Town is set between 1901 and 1913 in Grover’s Corners, New Hampshire, a community that has produced nobody very “important.” Wilder wrote that his subject was “the trivial details of human life in reference to a vast perspective of time, of social history and of religious ideas.” He was, he told us in an early preface to the play, presenting “the life of a village against the life of the stars.”

As Emily and others reflect on the meaning of their lives in their town, we may see our own experiences more clearly, wherever we live.

There is nothing ordinary about the backdrop of Wilder’s The Bridge of San Luis Rey, or the characters in his story. The novel is set in Lima, Peru, in the golden age of the 18th-century Spanish colonial empire. Among the exotic cast of characters are the greatest actress of the age, a drunken Marquesa who can’t stop writing letters, an obsessed Harlequin named Uncle Pio, identical twins with a private language, and a legendary ship captain. Nor does the novel lack drama, starting with the very first sentence: “On Friday noon, July the twentieth, 1714, the finest bridge in all Peru broke and precipitated five travelers into the gulf below.”

As different as these two works are in form and setting, they pose the same enduring questions that Wilder explored throughout his writing career—often employing death as the window to life. He could well have written of The Bridge of San Luis Rey as he wrote of Our Town: “It is an attempt to find a value above all price for the smallest events of our daily life.”

The Bridge of San Luis Rey

On a summer day in 1714, a bridge collapses in Peru, plunging five unsuspecting travelers to their deaths. Brother Juniper, a witness to the tragedy, dedicates himself to discovering why those five perished. Juniper’s work is judged heretical by the Inquisition and he and his findings are burned at the stake, but a secret copy survives. The narrator of The Bridge delves deeper into the lives of the victims: “Some say...that to the gods we are like the flies that the boys kill on a summer day, and some say, on the contrary, that the very sparrows do not lose a feather that has not been brushed away by the finger of God.”

Thornton Wilder’s second novel, The Bridge of San Luis Rey (1927) had diverse inspirations. The book’s philosophical underpinnings are rooted in Wilder’s conversations with his father, a devoted churchman, and in a passage in the gospel of Luke that reads, “...those eighteen upon whom the tower of Siloam fell and killed them, do you think that they were worse offenders than all the others who dwelt in Jerusalem?” Wilder often said that it is not the responsibility of a writer to answer a question but rather “to pose the question correctly and clearly.” Wilder later said, “The Bridge asked the question whether the intention that lies behind love was sufficient to justify the desperation of living.”

The action of the story has its origins in Wilder’s extensive reading of French literature, including the letters of Marquise de Sévigné and a short comic play by Prosper Mérimée, Le Carosse du Saint-Sacrement, about a notorious affair between the Viceroy of Peru and a famous actress called La Perichole.

Wilder began the novel in July 1926 during a residency at the MacDowell Colony, a writer’s retreat in New Hampshire, and just a year later the book was heralded by critics as a “masterpiece” and a “triumph.” The public agreed. The book sold out almost immediately. By the time it was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1928, it had already been through 17 printings and had sold nearly 300,000 copies.

The success of The Bridge allowed Wilder to resign his position at the Lawrenceville School to write and lecture full time. He used his royalties to build a home in Hamden, Connecticut, known as “The House The Bridge Built,” where he lived with his parents and sister Isabel.

Today, The Bridge remains a perennial favorite. Wilder’s novel continues to hold meaning for people the world over. In the wake of the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, British Prime Minister Tony Blair read from The Bridge’s closing lines at a memorial service for British victims of the World Trade Center attack: “There is a land of the living and a land of the dead and the bridge is love, the only survival, the only meaning.”

Major Characters

Brother Juniper, a “little red-haired Franciscan from Northern Italy,” has come to Peru to convert Indians when he witnesses the collapse of the bridge. He believes that by examining the “secret lives of those five persons” he can prove that their deaths were not by chance, but part of God’s plan.

Doña María, Marquesa de Montemayor, is the laughingstock of Lima. Silly and often drunk, she pines for the love of her daughter, Doña Clara, who has married and moved to Spain. Her desperation finds expression in beautiful letters that show a deep sensitivity, a vivid intelligence, and a heart breaking for the smallest kindness.

Pepita is an orphan brought up by “that strange genius of Lima,” Abbess Madre María del Pilar, before being sent to live in the Marquesa’s palace. While Pepita pities the Marquesa, she clings to “her sense of duty and her loyalty to her ‘mother in the lord,’ Mother María del Pilar.”

Camila Perichole is the greatest actress in Lima. Renowned for her beauty in her youth, she gains the favor of the court and the devotion of Uncle Pio. When her beauty is decimated by smallpox, she becomes reclusive. Although she refuses Uncle Pio’s help for herself, she entrusts to him her only son, Jaime, the bridge’s fifth victim.

Uncle Pio’s love of literature and culture is embodied in Camila Perichole, whom he trains as an actress. When his influence becomes overbearing, she rejects him. Years later, he still comes to her aid.

Esteban, another orphan raised by the Abbess, attempts suicide after the death of his twin brother, Manuel. He is setting out for a new life on the high seas when the bridge collapses and he falls to his death.

- Was Brother Juniper’s quest to prove God’s plan noble or foolish? Was the collapse of the bridge an accident, or was there intention? What is the narrator’s conclusion?

- How does the framing of the novel—a story examining an event 200 years prior—affect your reading? What does the passage of time add to our understanding of the characters? Why might Wilder choose not to tell the story from Brother Juniper’s point of view?

- Wilder had not been to Peru when he wrote The Bridge. How does his choice of detail and language heighten the sense of atmosphere and the believability of the characters?

- Why might Wilder have written The Bridge as a novel rather than a play? What aspects of the story are more appropriate to fiction than to drama?

- In what ways is The Bridge of San Luis Rey a fable? Does it teach a lesson? If so, what are we supposed to learn from the book?

- Does The Bridge have a hero? A villain? If so, what characteristics define these roles? Which characters were “good” and which were “bad” by Brother Juniper’s standards?

- Wilder’s Lima is populated by orphans, brothers, uncles, mothers, and matrons. How do these relationships conform to or deviate from your idea of family?

- Why does Doña Clara reject the Marquesa? Why does the Perichole reject Uncle Pio? Are they justified in their rejections? How might they feel after the deaths of the Marquesa and Uncle Pio?

- The Bridge is known for its aphoristic writing. What are some passages that stick in your mind? What makes them so memorable? What does this kind of writing add to the overall tone of the novel?

- In many ways, The Bridge is about love. What different forms of love can be found in the novel?