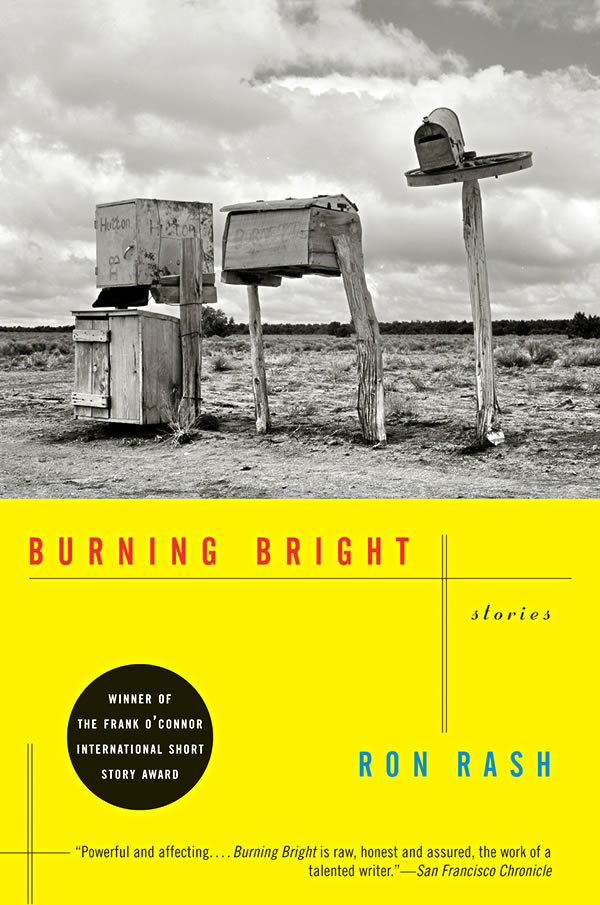

Burning Bright

Overview

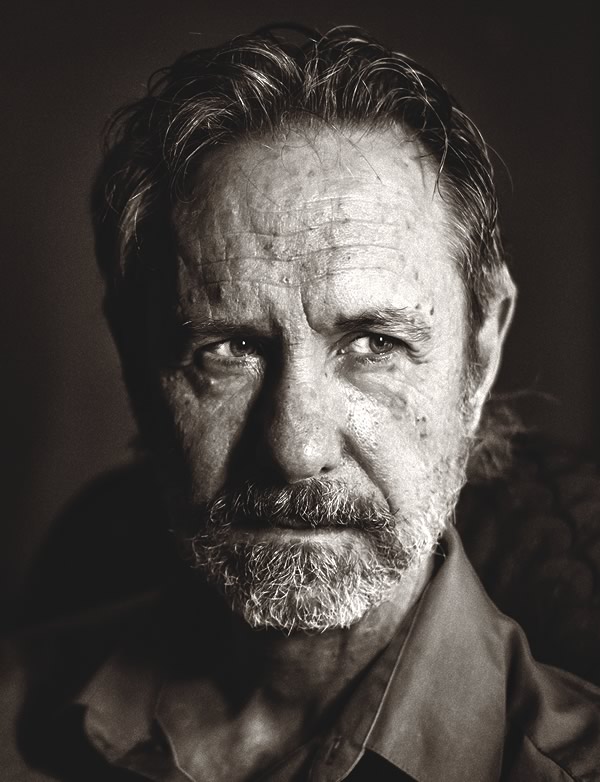

Ron Rash has been called “a national treasure” (Seattle Times), a “writer of quiet and stunning beauty” (Huffington Post), and “one of the best writers in America writing about Appalachia” (San Francisco Chronicle). A recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship and award-winning author of numerous volumes of poetry and prose, Rash “gathers several of the finest stories anyone could hope to read” (Irish Times) in his collection, Burning Bright, winner of the Frank O'Connor International Short Story Award. “The feral [and] beautiful stories in Ron Rash’s Burning Bright evoke Appalachians of a Civil War past—and a meth-blighted present—with the haunting clarity of Walker Evans photographs” (Vogue). The collection is “a slender set of spare and menacing depictions of the unforgiving ways of life in rural Appalachia,” noted the Washington Post. It “finds a narrow sweet spot between Raymond Carver’s minimalism and William Faulkner’s Gothic.” Highlighting the “purity and precision” of Rash’s writing, Booklist calls the stories “deceptively easy to read as they are hard to forget.”

"It's a lot easier to have a conscience about something if you figure it all the way right or all the way wrong."— from Burning Bright

Introduction

“The characters in Burning Bright are flawed … but they’re not monsters, even when their actions lack compassion or are downright criminal. The worst you can say about them is ‘They’re trying.’” – Pop Matters

Though the 12 stories in Burning Bright cover a wide swath of time from the Civil War to the present day, collectively they tell a story about Appalachia. And though they take us along the winding roads to the old homesteads and subdivisions of the American South, where “the region is a character in and of itself” and “myths and legends and history permeate every story” (BookPage), they also pulse with universal human emotions.

The collection lets us glimpse the lives of farmers and office workers, soldiers and war widows, pawnbrokers and old bar musicians, all struggling to exist in the world. “Rash’s characters…act as they believe they must to save what is dear to them—family members, a marriage, a heritage, a nation, and even a neighbor’s child” (Booklist). They “rely on gritty fortitude, shadowed compassion, and a bone deep alliance to the land and the people they came from to carry on, day to day” (Huffington Post).

The book opens with “Hard Times,” a story set during the Great Depression in which an impoverished farmer and his wife find some eggs missing from their henhouse. In their search for a culprit, their minds wander to their neighbor, a proud, honest man whose family has fallen on even harder times. A thinly veiled accusation prompts a swift, shocking response and ultimately a heart-wrenching revelation. “Any writer knows how to startle. Few can flesh out a simple story of, say, egg theft with the enormously effective understatement used here” (New York Times).

Following “Hard Times” is “Back of Beyond,” a story set in the modern era about a man who discovers the devastation that has befallen his brother and his brother’s wife as a result of their son’s crystal methamphetamine addiction. “These two stories, like everything in the collection, are peppered with essentially good people fallen on hard times; good people struggling to make ends meet and make sense of the world around them; good people trying to hold onto their humanity and dignity in the face of overwhelming pressure” (Independent).

Sometimes the pressure characters face comes not from the outside world but from their own beliefs, fears, and desires, especially if they conflict with the beliefs, fears, and desires of those around them. In “The Woman Who Believes in Jaguars,” an insomniac visits her local zoo and mistakenly accuses a passing woman of kidnapping a child that has reportedly gone missing. No one knows that the accuser once had a child who lived for only four hours. In “The Corpse Bird,” a father sees an owl and, remembering the lessons of his youth about nature’s signs—what others call superstitions—he becomes vehement in his attempts to persuade the parents of his daughter’s sick friend that she must go to the hospital or she will die. In the title story, “Burning Bright,” a newly-in-love, 60-year-old woman refuses to support her neighbors’ suspicions that her young husband may be an arsonist. Her “two-page trip to the grocery store where all of the town’s malice is embodied by one checkout cashier is yet another instance of Mr. Rash’s tactical precision” (New York Times).

“Highlighting the continuity of the human struggle over the ages,” Rash uses “a focused spotlight to illuminate a wider truth about society and our place within it” (Independent).

- The collection begins with “Hard Times” (p. 3), a story of life during the Depression when compassionate impulses and matters of pride sometimes conflicted with survival instincts. How do the adults in this story differ in their approach to surviving during hard times? Which of them do you think you’d be most like in such circumstances?

- Rash begins “Back of Beyond” (p. 19), “The Ascent” (p. 75), and “Return” (p. 127) with a description of a cold, snowy landscape. Why do you think he began these stories with a description of the setting? Why might he have chosen this specific environment?

- “It’s a lot easier to have a conscience about something if you figure it all the way right or all the way wrong,” says the narrator of the story “Dead Confederates” (p. 53). What do you think he means by this in the context of the story? In general, do you agree with the statement? Can you think of times in your own life when it was either easy or difficult to have a conscience?

- The stories “Back of Beyond” (p. 19) and “The Accent” (p. 75) explore the tragic impact that methamphetamine addiction can have on family members. In “Back of Beyond,” both the son (the addict) and his mother claim his wrongdoings are not his fault. Whom or what do they blame? Whom or what does the main character, Parson, blame? Who or what do you think is to blame in these stories? Why?

- By the end of “The Woman Who Believed in Jaguars” (p. 91), something “comes unanchored” inside Ruth, the main character. What do you think has come unanchored? Why?

- “Why couldn’t she act her age?” asks the daughter of Marcie, the main character in the title story “Burning Bright” (p. 116), echoing the sentiment of others in her community. What does it mean to act one’s age? If you were Marcie, would you have married Carl, despite your suspicions? Would you have told the sheriff what Marcie told him at the end of the story?

- Why do you think Rash chose the title of the story “Burning Bright” (p. 107) as the title for the full collection? What other story titles might also have worked as a title for the book? What story title would you have chosen as the title? Why?

- It has been said that the region in Rash’s writing often acts like a character in and of itself, such as in the story “Into the Gorge” (p. 133). What do you think this means? Do you agree? What are some of the characteristics of this region?

- The story “Falling Star” (p. 153) gives voice to a man who feels increasingly distanced from his wife when she goes back to school, fulfilling her desire to “make something” of herself. If you were to advise him on a different course of action—one that might save his marriage, his confidence, and his dignity—what would you tell him?

- In “The Corpse Bird” (p. 165), the main character, Boyd Candler, believes in the folklore of his ancestors and acts on those beliefs despite the disapproval of his community, most of whom believe such superstitions are not rational or enlightened. Would you have done what he did? Do you have myths and legends from your own family, or simply beliefs, that surface in your daily life and are different than those of others around you?

- How do the characters throughout these stories try and hold onto their humanity during challenging times? Do they succeed? Did you find as you were reading this collection that you were surprised by the choices they made? Or did you feel as if you’d have made the same choices?

- The bar patrons in the story “Waiting for the End of the World” (p. 181) are entranced with the song “Free Bird” by Lynyrd Skynyrd. Why? Can you think of something in your own life that gives you that same feeling?

- The last story of the collection, “Lincolnites” (p. 193) takes readers back to the Civil War era where a woman struggles to survive while she waits for her husband to return from service. In what ways does this story work as an ending to the collection? What does it leave you thinking about?

- Did this collection of stories confirm, illuminate, go against, or in some ways change your views about the Appalachian region and its people? If so, how?