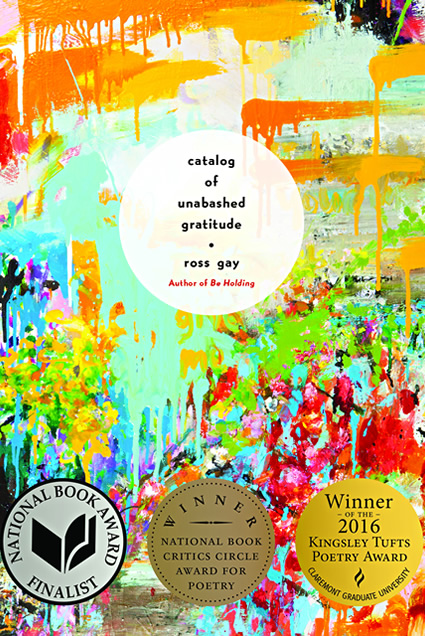

Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude

Overview

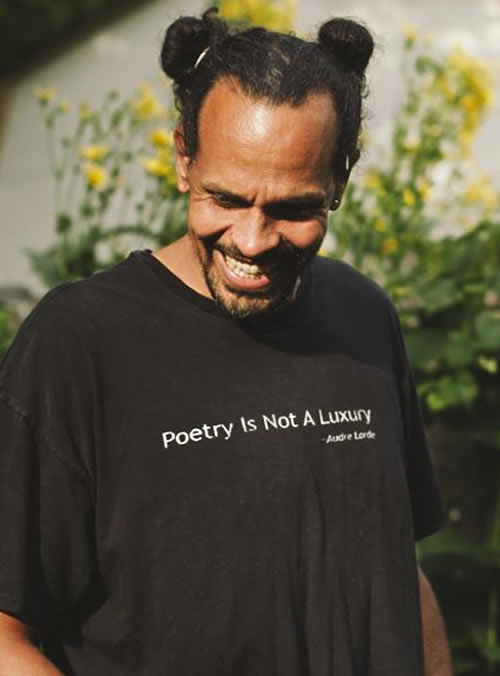

A poet, educator, and community gardener, Ross Gay tends to joy as one would an orchard—from seedlings to harvest, through all seasons of growth. In his collection, Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude, Gay demonstrates the practice of gratitude while never losing sight of the loss that animates it. He draws readers in with flesh and fruit in poems that“feel bold and wild and weird” (American Poetry Review). “Almost no one has the faith Gay seems to have in poetry’s ability to tap grace from the happenings of his life…” (Paris Review). Reading the book “feels like the first time you open the window in spring. That first chilly air. The sun on the sill” (Poetry Foundation). “Whether you’re feeling like you have a whole brass band of gratitude or if you’re feeling like you only have a rusty horn, read this book” (National Book Critics Circle).

“What do you think / This singing and shuddering is, / What this screaming and reaching and dancing / And crying is, other than loving …” — Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude

Through 24 lyric poems, Ross Gay’s Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude offers a luminous exploration of death, life, and their many tides. Animated by what Gay has called the “discipline of gratitude,” the collection considers sorrow’s potential, grounded in the rhythms and abundance of the natural world: the compost that gives way to rich soil, the decay that reveals seeds, the branches that must be trimmed to make room for new growth. Mistakes can be landscapes of new possibilities, he seems to say. With warmth and gratitude and often humor, he roots his poems in deeply personal experiences while noting that impermanence is one of the threads that connect us: “we have this common experience—many common experiences, but a really foundational one is that we are not here forever” (On Being).

Though suffering and sorrow wend their way through each poem, adopting various guises, they are met everywhere by a commitment to this cycle of transformation. Gay sees the twinning of loss and abundance as an astonishing opportunity for tenderness and joy, and the poems in Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude are intimate, conversational. “I trust people who, in the same conversation, use more than one voice, more than one register. Maybe it speaks to a kind of urgency. But I think it might, more accurately, speak to a kind of intimacy,” Gay told the Rumpus. Throughout the collection, Gay addresses his readers directly, as an old friend might, and invites them to observe the gentle, loving labor of bees; to taste sweet fruit-flesh; to smell sweet potato biscuits frying in coconut oil; to stay awhile and sip honeyed tea; to leave, warm and fed, when they are ready to go; to know they will be missed.

In an interview with the Poetry Foundation, Gay shared: “[The book] wants to be nuts-in-love…And that can feel really terrifying, that kind of real openness or attempt at openness—I’ll speak for myself—that feels scary....” Love, in other words, is a sustained practice: care reified through the work of vulnerability. Delight and gratitude in the face of impending loss is a fearsome prospect, but Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude shows us, again and again, that it is precisely this kind of openness that allows for growth and joy. Open the self, Gay suggests—open the heart—and you open “huge windows through which light / Pours to wash clean and make a touch less awful // What forever otherwise will hurt” (p. 41).

- In “Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude,” Gay writes, "I can't stop my gratitude, / Which includes, dear reader, / You, for staying here with me, / For moving your lips just so as I speak. / Here is a cup of tea. I have spooned honey into it." (p. 86) What ways do you show gratitude in your life? What actions bring you delight or gratitude? How do you like others to express gratitude for you?

- In the same poem, Gay recounts a dream in which a robin on a branch growing into his window speaks to him: “"it said so in a human voice, / "Bellow forth"— / And who among us could ignore such odd / And precise counsel?" (p. 82-83) What might Gay be offering in this poem about the lessons that we can learn from the natural world? Are there other moments in the collection where something in nature provides a lesson or “counsel”? Can you think of a time in your own life when an animal or plant taught you something?

- In the poem "To the Fig Tree on 9th and Christian,” Gay writes about picking figs alongside strangers at an intersection in his town. The poem closes with the lines, "we are feeding each other / From a tree / At the corner of Christian and 9th / Strangers maybe / Never again" (p. 6). What place or places in your own neighborhood, towns, or communities bring people together by chance in meaningful ways? What are the qualities of that place or those places?

- “I’m a survivor, I survived,” (p. 39) says Don Belton, the 53-year-old gay Black man to whom the poem “Spoon” is dedicated. What makes this statement particularly powerful for this man, in our society, in this poem?

- Gay frequently addresses his readers directly, either as a collective (“friends!”) or as an individual you, as in “Last Will and Testament” (“but you get my point, friend”, p. 98) or “Feet” (“...do you really think I’m talking to you about my feet?” p. 21). Why do you think he uses this approach? How did this affect your reading experience? Can you think of other works of art that address their audiences directly?

- In an interview with On Being about his work, Gay said: “…among the things of that thing connecting us is that we have this common experience—many common experiences, but a really foundational one is that we are not here forever. And that’s a joining—a “joy-ning.” How are “joy” and “joining” linked in your own life? Did your experience with joy change for you in some way during the pandemic? Were there any new or unexpected ways that you found yourself joining with your communities?

- Gay seems to be intent on making himself vulnerable in these poems. He shares insecurities, fears, and mistakes; he apologizes to readers; he seems to allow his poems, sometimes, to “fail.” Are there moments of vulnerability in the book that stood out to you, or that caught you off guard? Why do you think vulnerability is so important to Gay?

- In “To the Mistake,” Gay writes: “…the mistake / I say is a gift / don’t be afraid / see what it teaches you ….” (p. 47) Can you find descriptions of “mistakes” in this and the other poems in the collection that might be interpreted as gifts or teachable moments? Can you describe a mistake that you or someone else made that taught you something?

- In some of these poems, Gay chooses to describe the physical effect of emotions rather than naming them. What do you think motivates that choice? In many, he replaces emotions with animals in the body, as in “Armpit,” where he writes: “I’m trying to get / to the awkward flock / of flamingoes soaring / somewhere below my navel or / in the back of my throat…” (p 30), or in “Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude,” where he describes his “heart like an elephant screaming / at the bones of the dead…” (p. 92). What effect do these images of animals have on you as you read the poem? How might you use descriptions of the natural world to relate common emotions like anger, gratitude, or sorrow?

- In poems like “Weeping,” Gay describes things by describing what they are not: “...Emma must have flown away for good, judging / by the not brutal silence at breakfast…” (p. 43). He does this again in “Ending the Estrangement,” where he writes: “it felt to me / not like what I thought it felt like / to her…” (p. 59). These descriptions expand the possibilities of what a thing is. What are some other things that can best be described by identifying what they are not?

- On a related note: in the title poem, Gay includes in his gratitudes “the ancestor who loved you / before she knew you…” by smuggling seeds, planting trees, not slaughtering the land, not bulldozing trees, “...who did not fire, who did not / plunge the head into the toilet, who said stop, / don’t do that…” (p. 90). What have your ancestors or predecessors done to love you before they knew you? What did they not do? What are you doing—–or what do you hope to do—to love generations to come?

- Some of the gratitudes in this book seem, at first glance, to run contrary to the ways we’re taught to be thankful and the things we’re taught to be thankful for. In “Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude,” for example: “...thank you for taking my father / a few years after his own father went down…thank you / for leaving and for coming back…” (p. 84) Does being grateful for loss or hardship change the loss or hardship in some way? Does it change us?

- The poems in Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude are largely written in free verse, rather than a more rigid poetic mode. But while some poems, like “Weeping” or “The Opening” favor long, Whitmanesque lines—some reaching all the way to the edge of the page—others are written with short, clipped lines of only a few words, like “Ode to Buttoning and Unbuttoning My Shirt” or “Wedding Poem.” Do these poems feel different as you read them? What if you read them out loud?

- “Last Will and Testament,” like “Burial,” considers—at times in creative and unconventional ways—what is to be done with the body after death: “oh for god’s sake / have a little fun / with this grave and grizzly drill / and know I’m giggling too / and feel nary a thing” (p. 95). What might be some creative and unconventional messages you might like to offer to your surviving loved ones?