Citizen: An American Lyric

Overview

Jamaican-born author Claudia Rankine is the author of five collections of poetry, two plays, and numerous video collaborations. Citizen: An American Lyric is sweeping the country, already chosen by dozens of schools and centers as a community read book. It was a finalist for the National Book Award in poetry and winner of the NAACP Image Award, the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, the PEN Open Book Award, and the National Book Critics Circle Award in poetry while at the same time was a finalist for the same award in criticism. It was also named one of the best books of the year by numerous media outlets, including The New Yorker, The Atlantic, National Public Radio, and Publisher's Weekly. The book lays bare moments of racism that often surface in everyday encounters. It combines poetry with commentary, visual art, quotations from artists and critics, slogans, and scripts for films. It's "an anatomy of American racism in the new millennium" (Bookforum).

"Feel good. Feel better. Move forward. Let it go. Come on. Come on. Come on." —from Citizen: An American Lyric

Introduction

"I love language because when it succeeds, for me, it doesn't just tell me something. It enacts something." — Claudia Rankine in Guernica

Claudia Rankine's Citizen: An American Lyric, published by Graywolf Press in 2014, is the first work of poetry to become a New York Times bestseller for multiple weeks on the paperback nonfiction list. It won the National Book Critics Circle Award in poetry, and was also a finalist for the award in criticism, the first time in the history of those awards that a book was named a finalist in more than one category. "A classic that will be read, referred to and reflected on for generations" (Lit Hub), Citizen is a genre-bending work of art combining lyric prose with internal monologues, visual art, slogans, photographs, quotes, a screen grab from YouTube, and film scripts. It is a touchstone for talking candidly about racism. And it is a time capsule of contemporary headlines and key figures, with references to, among other things, Hurricane Katrina, the tennis champion Serena Williams, the 2006 World Cup, and the fatal shooting of Florida resident Trayvon Martin. "So groundbreaking is Rankine's work that it's almost impossible to describe," writes the Los Angeles Times. It "forces you to observe: what's outside the window, what's on the television, what's at the margins of the painting, and what's happening—whether you admit it or not—at the margins of your mind" (The Believer).

Through a series of vignettes, the book recounts everyday moments of racism "of a kind that accumulate until they become a poisonous scourge: being skipped in line at the pharmacy by a white man, because he has failed to notice you in front of him; being told approvingly, as a schoolchild, that your features are like those of a white person; being furiously accosted by a trauma therapist who does not believe that the patient she is expecting could look like you" (The New Yorker). "I started working on Citizen as a way of talking about invisible racism—moments that you experience and that happen really fast," Rankine told The New Yorker. "They go by at lightning speed, and you begin to distrust that they even happened, and yet you know that you feel bad somehow." She asked friends to share stories of those moments, and then combined them with stories of her own moments and those she observed in our culture. "We are social animals, " she told The Spectacle. "We want connection. We want ... understanding. We want intimacy. But if the terms of that intimacy feel dishonest, or feel only possible with the acceptance of your erasure, then that's painful." Rankine frequently uses the second person "to say, 'Step in here with me, because there is no me without you inside this dynamic'" (Buzzfeed).

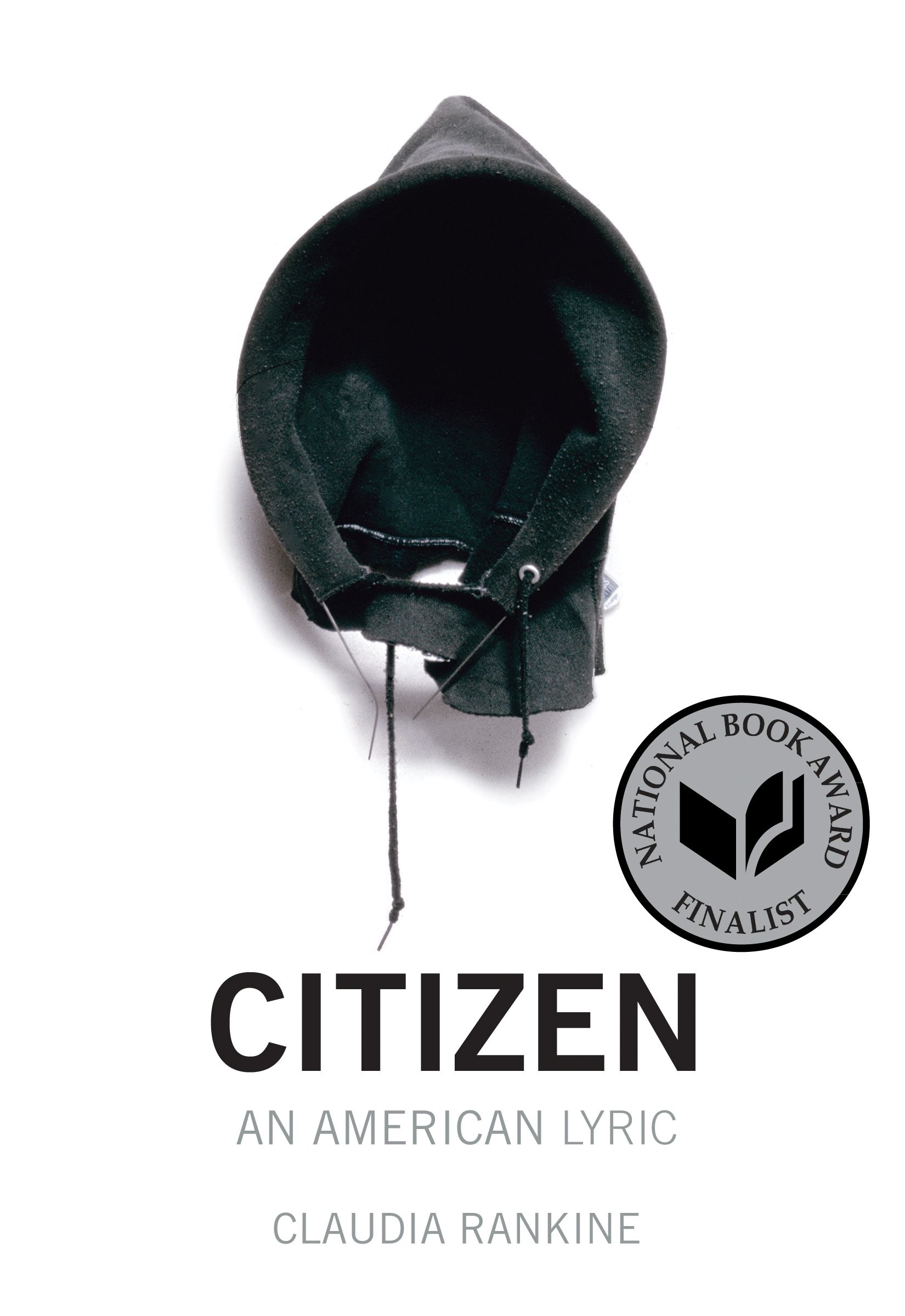

The book's unusual trim size and heavier paper hint at the beauty and weight of what readers will discover inside its pages, as does the book's cover art, a 1993 piece called "In the Hood" by artist David Hammons. Similarly, the artwork inside the book reverberates off the words. "I was attracted to images engaged in conversation with an incoherence ... in the world," Rankine told BOMB Magazine. "They were placed in the text where I thought silence was needed, but I wasn't interested in making the silence feel empty or effortless the way a blank page would." Amidst a piece detailing Williams' frustrations on the tennis court is a photo of a "Soundsuit," an art piece by the fabric sculptor, dancer, and performance artist Nick Cave. "If the person wearing this suit stood up, what you would see is a dark black covering," explains Rankine to The Believer. "But if she bent over, than you got this kind of beautiful color that was acceptable, even dazzling, to whoever was looking. I thought this enacted the public expectations for Serena, the desire for her to look a certain way."

Among the many other awards Citizen has received are the Los Angeles Times Book Prize in poetry, the Forward Prize for Best Collection in Great Britain, the NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Literary Work, the PEN Open Book Award, and the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award in poetry; the book was also named a finalist for the National Book Award in poetry and the T. S. Eliot Prize in Great Britain, and was performed on stage at the Fountain Theatre in Los Angeles. Rankine "is a writer whose genius must be trusted," says her editor at Graywolf, Jeff Shotts. "Often the vision is larger than the page ... but then seeing the multi-faceted ways that she finds to present the work inside the vessel of the book is amazing."

Asked what her motto is, Rankine refers to the collagist Romare Bearden. "He said, 'There are all kinds of people, and they will help you if you let them.' As somebody who collaborates a lot, I take that to heart, and I certainly would hope that other people would see me as one of those people who would help them, if they would let me" (Radio Open Source).

To learn about using Citizen: An American Lyric as a teaching tool, check out this resource on the publisher's website.

A Behind-the-Scenes Look at Editing Claudia Rankine's Citizen (Art Works Blog, 4/14/2017)

How to Read and Talk About Poetry (Art Works Blog, 12/2/2016)

What do you think it means to be a “citizen”? What words, definitions, or ideas do you associate with “citizenship”? Did reading this book make you think about the term in a new way?

Rankine uses a second-person perspective throughout the book, addressing much of the text to “you.” How do you feel the use of this perspective affected your reading of the book? What angles of experience were you surprised to inhabit, and why?

The term “lyric” might first bring to mind the words of a song. It is also a term used to describe poetry in which a speaker directly expresses personal thoughts or emotions. Why do you think Rankine chose to use the subtitle “An American Lyric”? What do you think is “American” about what takes place in the book, and how do you interpret “lyric” in this context?

The cover artwork, In the Hood by David Hammons, was first exhibited in 1993. What historical associations does the image bring up for you? What about modern day associations? In what ways do you think having information about a work of art (date, title, historical context, etc.) changes the way you view or understand it?

Citizen's discussion of Serena and Venus Williams includes the Zora Neale Hurston quote, “I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background” (p. 25). How might this quote relate to the Williams sisters' experience in the world of professional tennis? Can you think of other examples in American culture or society where Hurston’s quote seems applicable?

Referring again to Serena Williams, Rankine states, “...the body has memory. The physical carriage hauls more than its weight” (p.28). What memory or memories might Rankine be referring to here?

On p. 131, Rankine narrates the act of sitting down in an empty seat next to a man on a train, a seat others have avoided. How would you describe the scene that unfolds, and its significance to those involved? Can you think of times when you’ve been hyperaware of the physical space you occupy? What caused that awareness, and how did it feel?

How does Citizen portray and address privilege in America? How does Rankine show the effects of privilege on those who have it? On those who don’t?

What do you make of Rankine’s choice to use J.M.W. Turner's painting The Slave Ship (p.160) as the concluding image in Citizen? Why do you think a close-up image of one portion of the artwork (“Detail of Fish Attacking Slave”) is pictured alongside the full painting?

From screenshots to collages, photographs to paintings, visuals play an essential role in Citizen. How did the inclusion of these visual images affect your reading of the book?

As Citizen has been reprinted, the different editions have incorporated changes to the text—most notably, the inclusion on p. 134 of the names of African Americans killed since previous printings. How does this evolution align with the book's core questions and themes? Why do you think Rankine chose to take this approach, when most books remain unchanged over time?

Many readers and critics have pointed out that Citizen defies established genre distinctions (for example, it was nominated for National Book Critics Circle Awards in both the Poetry and Criticism categories). Reading Citizen, did you think of it as poetry? As prose? Fiction? Nonfiction? Does it matter?

The book is divided into seven sections. What do you think distinguishes the sections from each other, and why do you think Rankine chose to structure the book in this way?

Rankine played a significant role in the design and production of Citizen—from deciding on the compact size of the book, to settling on the heavy weight and stark white color of the paper. How do the physical qualities of the book contribute to your experience of reading and understanding it?

Discussion questions adapted from source material provided by Graywolf Press.

Lighthouse Writers Workshop Gets Creative With Citizen on the Stage and on the Sidewalk in Denver, CO

|

|

“We knew we wanted to go beyond book talks and engage with participants on multiple levels. So we reached out to a local theater troupe and they staged the play version of Citizen. We talked to a ballet company, and they performed a duet based on the Trayvon Martin case, followed by a free-write. Two of our partners were a nonprofit art school and a community gallery, so we worked with them to create programming that would appeal to their audiences. One wound up creating a Citizen-themed mural, and the other led a poem box workshop (which was actually an idea one of our volunteers brought to us—she’s a huge Citizen fan and had been making poem boxes for years!). We just find that people love to participate and create, and we wanted to give them the opportunity to do that.”

|

|

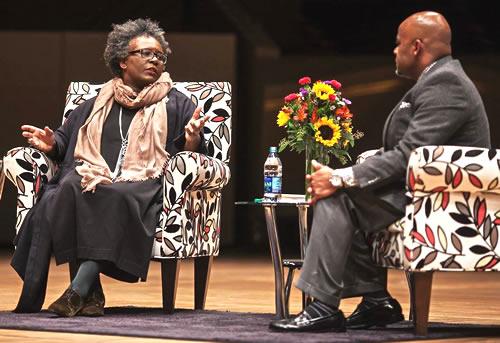

“Claudia’s talk drew 1,800 people, and she received a standing ovation when she walked out on stage, which was powerful to witness. And so many of the community events were uplifting in the best way. One night, we participated in a program called Moveable Feast, where participants ate a locally produced dinner in an urban park, wrote responses to Citizen-themed prompts and then took turns reading what they wrote in front of everyone. Most of the people there didn’t know each other, but by the end of the night, everyone felt closer, having shared food and this experience.”

|

|

|

– from an interview by Arts Midwest with Lighthouse Writers Workshop, an NEA Big Read grant recipient in FY 2016-17.