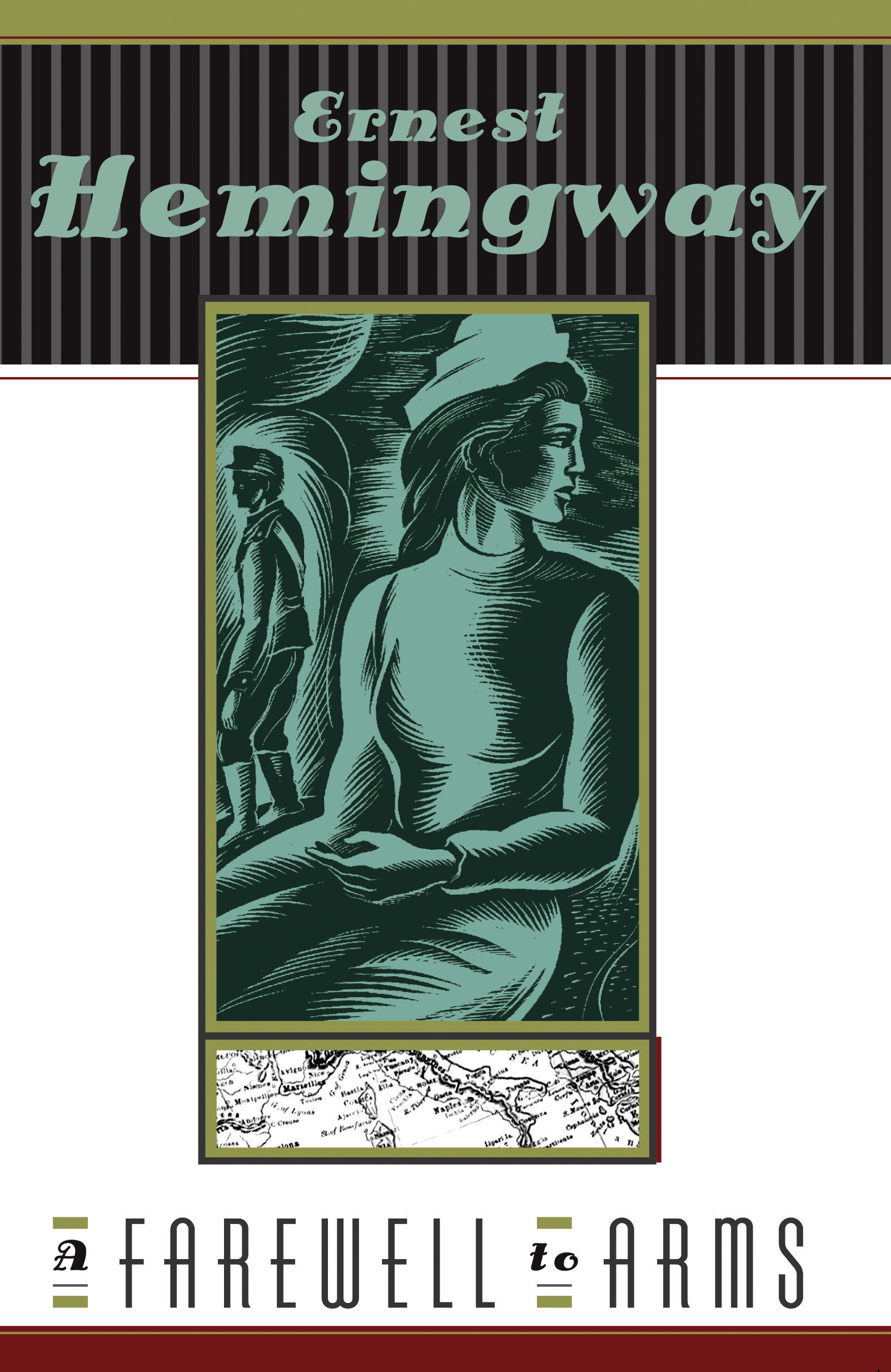

A Farewell to Arms

Overview

Ernest Hemingway is the notorious tough guy of modern American letters, but it would be hard to find a more tender and rapturous love story than A Farewell to Arms. It would also be hard to find a more harrowing American novel about World War I. Hemingway masterfully interweaves these dual narratives of love and war, joy and terror, and—ultimately—liberation and death.

It will surprise no one that a book so vivid and deeply felt originated in the author's own life. Hemingway served as an ambulance driver for the Italian army in World War I. Severely wounded, he recuperated in a Red Cross hospital in Milan where he fell in love with one of his nurses. This relationship proved the model for Frederic and Catherine's tragic romance in A Farewell to Arms.

"All good books are alike in that they are truer than if they had really happened and after you are finished reading one you will feel that all that happened to you and afterwards it all belongs to you..." —from the essay "A Letter to Cuba"

Overview

Ernest Hemingway is the notorious tough guy of modern American letters, but it would be hard to find a more tender and rapturous love story than A Farewell to Arms. It would also be hard to find a more harrowing American novel about World War I. Hemingway masterfully interweaves these dual narratives of love and war, joy and terror, and—ultimately—liberation and death.

It will surprise no one that a book so vivid and deeply felt originated in the author's own life. Hemingway served as an ambulance driver for the Italian army in World War I. Severely wounded, he recuperated in a Red Cross hospital in Milan where he fell in love with one of his nurses. This relationship proved the model for Frederic and Catherine's tragic romance in A Farewell to Arms.

Introduction to the Book

Ernest Hemingway's third novel, A Farewell to Arms (1929), was crafted from his earliest experience with war. As a teenager just out of high school, Hemingway volunteered to fight in the First World War but was rejected because of poor eyesight. Instead, he drove a Red Cross ambulance on the Italian front, where he was wounded in 1918 by a mortar shell. While recovering in a hospital, Hemingway fell in love with Agnes von Kurowsky, a nurse seven years his senior. She did not reciprocate his passion, however, and rejected his marriage proposal five months after their first meeting.

These events were thinly fictionalized by Hemingway a decade later into A Farewell to Arms, with its tragic love story between an American ambulance driver and an English nurse. Lieutenant Frederic Henry meets Catherine Barkley in a small town near the Italian Alps. Though Catherine still mourns the death of her fiancé, killed in the war, she encourages Frederic to pursue her. Badly wounded at the front, Frederic finds himself bedridden in a Milan hospital, but Catherine arrives to look after him. It is here that their initial romance deepens into love. While Frederic recovers from surgery and prepares to return to action, Catherine discovers that she is pregnant—a surprise that delights and frightens them both. Though the couple has escaped the war, there are dangers that cannot be anticipated or avoided. The final chapter is one of the most famous, and heartbreaking, conclusions in modern literature.

This rather simple plot does not explain the appeal of A Farewell to Arms. It is Hemingway's writing style that transforms the story into a great tragedy. The critic Malcolm Cowley considered it "one of the few great war stories in American literature; only The Red Badge of Courage and a few short pieces by Ambrose Bierce can be compared with it." By omitting most adjectives and using short, rhythmic sentences, Hemingway tried to give the reader a sense of immediacy, of actually witnessing the events in his writing. He once described his method this way: "I always try to write on the principle of the iceberg. There is seven-eighths of it under water for every part that shows. Anything you know you can eliminate and it only strengthens your iceberg." His spare prose and laconic dialogue made him the most widely imitated American writer of the 20th century.

"All good books are alike in that they are truer than if they had really happened and after you are finished reading one you will feel that all that happened to you and afterwards it all belongs to you; the good and the bad, the ecstasy, the remorse and sorrow, the people and the places and how the weather was."

—Ernest Hemingway, from the essay "A Letter to Cuba"

- What do we know of Frederic Henry's and Catherine Barkley's lives before the novel begins? As the novel's narrator, why would Frederic choose to tell us so little about their past?

- At the beginning of their romance, Frederic treats his relationship with Catherine like a game. When does he fall in love? Why does it happen?

- What role does religion play in the novel? How does Frederic's view of the priest compare to the other officers'?

- Why is Catherine afraid of the rain? Why does Frederic fear the night? How do both the rain and the night foreshadow the novel's tragic conclusion?

- Even before the retreat at Caporetto, Frederic considers that "abstract words such as glory, honor, courage" are "obscene beside the concrete names of villages." What does he mean by this?

- Identify a passage that vividly describes World War I. Does the novel make any assertions about war in general, or World War I in particular?

- After his desertion, Frederic says that, "anger was washed away in the river along with any obligation." Are his actions justified?

- The novel's action begins in the late summer of 1915; it ends in spring 1918. Has Frederic changed during this period of time? Is there any redemption at the end of this tragedy?

- Toward the end of the novel, Count Greffi tells Frederic that love is a religious feeling. Does Frederic agree? Why or why not?

- How would you describe Hemingway's style of writing and his characters' dialogue?

- The words "bravery" and "courage" are echoed through the novel. Who is the novel's hero? Who is the most courageous character?