Interior Chinatown

Overview

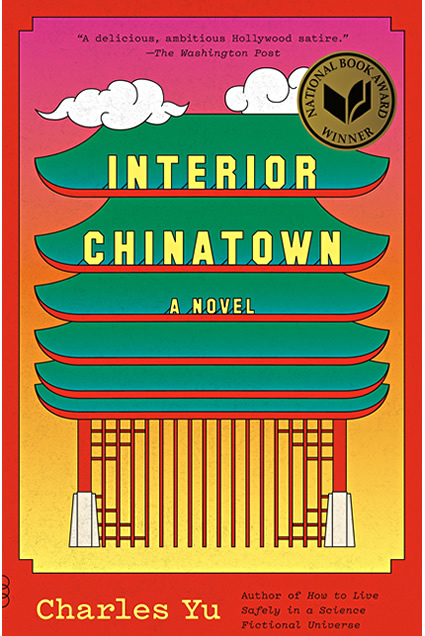

Charles Yu’s critically acclaimed second novel Interior Chinatown is “satire at its best, a shattering and darkly comic send-up of racial stereotyping in Hollywood…presented, perfectly, in the sharply hewed format of a screenplay” (Vanity Fair). Winner of the 2020 National Book Award for Fiction, the novel is "a moving exploration of race and assimilation" (San Francisco Chronicle), "both rollicking entertainment and scathing commentary" (Booklist), and "a parable for outcasts feeling invisible in this fast-moving world" (Kirkus Reviews). It tells the story of Willis Wu, who has only ever been cast as the Generic Asian Man. Consigned to bit roles in the background of a procedural cop show, he dreams of playing Kung Fu Guy, the most respected role that anyone who looks like him can attain—or so he has always been told. The novel “recalls the humorous and heartfelt short stories of George Saunders, the metafictional high jinks of Mark Leyner, and films like The Truman Show” (New York Times). It’s “honest, funny, sad, and necessary…” (Thrillist).

“Working your way up the system doesn’t mean you beat the system. It strengthens it. It’s what the system depends on.” — Interior Chinatown

As a bit player on the set of a police procedural, Black and White, Willis Wu dreams of one day playing Kung Fu Guy, “…the ceiling, the terminal, ultimate, exalted position for any Asian working in this world” (p. 12). In the Golden Palace restaurant where Black and White is in perpetual production, Asian actors are relegated to the background, their identities reduced to stereotypes: the “Pretty Oriental Flower,” the “Egg Roll Cook,” the “Oriental Guy Making a Weird Face.” In the seven floors above the Golden Palace, however, there exists a vibrant world. Each floor is a complex ecosystem with its own rules and territories, love stories and old wounds, shared and private hungers. Across the pages of Interior Chinatown, Charles Yu locates humanity in the overlooked and everyday, chronicling “life at the margins, made from bit pieces” (p. 256). A mother’s love is distilled into a cup of fruit punch, communication networks are sketched through laundry lines, the passage of time is brought to life in the texture of a kitchen table.

Throughout the novel, fiction exerts itself on reality. There is no way to escape the world of Black and White, no way to move forward outside of an established hierarchy. When the show enters the Golden Palace, gongs sound from nowhere and everywhere. Chinatown itself is a land of aborted possibilities, a “pretend version of the old country” (p. 58) where generations repeat the same cycles of arrival and return. Willis’ parents age from “Beautiful Maiden Number One” to “Old Asian Woman,” from “Young Asian Man” to “Wizened Chinaman.” Hollywood-staged deaths bring a kind of freedom, mandating that performers take time away from the show: “Some of the happiest times of your life were when your mother was dead, because you knew it meant…you would have her all to yourself in the afternoons,” Yu writes. “When she was dead, she got to be your mother” (p. 130).

As his career grows, Willis falls in love and starts a family of his own. Through his new role as a parent, he discovers more about his own parents’ buried dreams, the secret histories of Chinatown, and his own potential to write a different story for them all. “Can you tell me a story?” Willis’ daughter asks. “I don’t know how. No one’s ever asked me to,” he says. “Can you try?” she answers.

Taking the form of a screenplay—right down to the use of Courier, a standard font for screenplays—the novelexamines the shifting lines between performance and self, assimilation and authenticity. In spare, careful prose, Yu interrogates both the systems that dehumanize, and the roles we play to survive within them: whether we know it or not. It is love and community, he seems to say, that offer another way through: towards a world with no plot, no show, just people and the sky above.

- Interior Chinatown is structured and formatted like a screenplay, complete with acts, scene headings, and centered text. Was this approach familiar to you? Did it affect your reading experience? If so, in what ways?

- Each act of Interior Chinatown is preceded by an epigraph by the author Bonnie Tsui and/or the sociologist Erving Goffman. What did you make of these quotes? Did any of them especially resonate with you, or illuminate a particular aspect of the novel?

- Throughout the book, performance occurs beyond the set of Black and White. Willis’ father is depicted in the “theater of his dotage” (p. 19), and Chinatown itself is identified as something that “...is and always has been, from the very beginning, a construction, a performance of features, gestures, culture, and exoticism” (p. 239). Are there any other moments in the novel where you noticed a kind of performance taking place in an unexpected way? Are there areas of your own life where you find yourself or others “performing”?

- Throughout Interior Chinatown, the character Older Brother is never named; he is only referred to by his role on Black and White. Are there any other characters who are never named? How did this affect your reading of those characters vs. the ones with names?

- In the world of the show Black and White, Willis notes that: “Black and White always look good. A lot of it has to do with the light. They’re the heroes. They get hero lighting designed to hit their faces just right. Designed to hit White’s face just right, anyway” (p. 11). Think about the issue of race in this quote and in the novel itself. Does anything resonate with you? Surprise you? Who do you think is shining the light that’s creating our heroes?

- When introducing Older Brother, Willis notes that “Bruce Lee was the guy you worshipped. Older Brother was the guy you dreamt of growing up to be” (p. 25). What is the difference between someone you “worship” and someone you could “grow up to be”? Who are the heroes and role models in Interior Chinatown? Does this change over the course of the novel?

- In Act III, Willis describes the following interaction with his father: “He says something you don’t quite follow. You hear it, you catch most of the individual words, and yet somehow—you don’t understand. This gap, always there. Somehow unbridgeable, whether it’s across a wide Pacific gulf of language and culture, or just a simple sentence, father to son, always distance” (p. 90). Consider times when it was difficult for you to communicate with people from a different generation than your own. What made it difficult? Were you able to relate to each other in the end? If so, how?

- When Willis breaks character to speak to his father, he speaks “...not in Mandarin, but Taiwanese. The family language, the inside language. A secret code” (p. 90). Across the novel, how do language and dialect create connection? What can language reveal? How does it disguise?

- In Act IV, Willis dives into flashbacks that describe his parents’ background and his childhood: “...the first times start turning into last times, as in, last first day of school, last time he crawls into bed with us, last time you’ll all sleep together like this, the three of you. There are a few years when you make almost all of your important memories. And then you spend the next few decades reliving them.” (p. 158) In what way do these flashbacks deepen your understanding of their family? What are some family stories that give you insight into family relationships and dynamics?

- Across the book, scenes shift between “exterior” and “interior” spaces, from Chinatown to the single residence occupancy units where Willis and his friends and family live. How did these physical settings change your experience of the novel? Were there any moments in the book where you felt a particularly strong sense of place? What stood out to you about those moments?

- As the novel progresses, the screenplay format does not always hold true: actors break character, go off-script, leave the set. Consider moments where Yu deviates from the structure of a screenplay. Do these moments change your understanding of Willis’ story?

- Interior Chinatown is filled with a lot of satirical, dark humor. Were there any scenes in particular that made you laugh? What does humor add to the story?

- In Act VI of the novel, Yu includes short timelines tracking the restrictive state and federal laws that have affected Asian and immigrant communities: from the United States Geary Act (p. 216) to the Chinese Exclusion Act (p. 259). Were you familiar with any of these pieces of legislation before you encountered them in the novel? Did the inclusion of these historical accounts make you think about the novel in a new way?

- The book depicts three generations of the Wu family: from Willis’ parents and their journey from Taiwan to the United States, to Willis, to his daughter, Phoebe. How does Yu show the evolution of these three generations’ relationships with America and Americanness?

- Yu uses a second person point of view throughout the book. Have you read other books or stories that have used this point of view? How did Yu’s use of the second person affect your reading of the book?

Source material for Interior Chinatown discussion questions from Penguin Random House.