A Lesson Before Dying

Overview

This title will no longer be available for programming after the 2020-21 grant year.

The oldest of 12 children, Ernest J. Gaines was born in 1933 and grew up impoverished on a cotton plantation in Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana. In 1948, he moved to Vallejo, California, and spent much of his time at the local library reading and writing, endeavors that eventually led him to earn a creative writing degree from Stanford University, a 1968 National Endowment for the Arts creative writing fellowship, a MacArthur Foundation fellowship, and the National Medal of Arts. Set in the rural south in the 1940s during Jim Crow laws and racial segregation, Gaines’s eighth novel, A Lesson Before Dying, tells the story of a falsely-accused young black man on death row and a Louisiana-born, college educated teacher who visits him in prison and helps him regain his dignity. It won the National Book Critics Circle Award in 1993. “Gaines has a gift for evoking the tenor of life in a bygone era and making it seem as vivid and immediate as something that happened only yesterday” (Christian Science Monitor). The Chicago Tribune writes, "[t]his majestic, moving novel is an instant classic, a book that will be read, discussed and taught beyond the rest of our lives."

“I want you to show them the difference between what they think you are and what you can be.” —from A Lesson Before Dying

Introduction

Ernest J. Gaines's A Lesson Before Dying (1993) poses one of the most universal questions literature can ask: Knowing we're going to die, how should we live? It's the story of an uneducated young black man named Jefferson, accused of the murder of a white storekeeper, and Grant Wiggins, a college-educated native son of Louisiana, who teaches at a plantation school. In a little more than 250 pages, these two men named for presidents discover a friendship that transforms at least two lives.

In the first chapter, the court-appointed lawyer's idea of a legal strategy for Jefferson is to argue, "Why, I would just as soon put a hog in the electric chair as this." This dehumanizing and unsurprisingly doomed defense rankles the condemned man's grief-stricken godmother, Miss Emma, and Grant's aunt, Tante Lou. They convince an unwilling Grant to spend time with Jefferson in his prison cell, so that he might confront death with his head held high.

Most of the novel's violence happens offstage in the first and last chapters. Vital secondary characters punctuate the narrative, including Vivian, Grant's assertive yet patient Creole girlfriend; Reverend Ambrose, a minister whom the disbelieving Grant ultimately comes to respect; and Paul, a white deputy who stands with Jefferson when Grant cannot.

White, black, mulatto, Cajun, or Creole; rich, poor, or hanging on; young, old, or running out of time—around all these people, Gaines crafts a story of intimacy and depth. He re-creates the smells of Miss Emma's fried chicken, the sounds of the blues from Jefferson's radio, the taste of the sugarcane from the plantation. The school, the parish church, the town bar, and the jailhouse all come alive with indelible vividness.

In the tradition of Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird (1960) and Truman Capote's In Cold Blood (1966), Gaines uses a capital case to explore the nobility and the barbarism of which human beings are equally capable. The story builds inexorably to Jefferson's ultimate bid for dignity, both in his prison diary and at the hour of his execution. That Ernest J. Gaines wrings a hopeful ending out of such grim material only testifies to his prodigious gifts as a storyteller.

How A Lesson Before Dying Came to Be Written

The following is excerpted from Ernest J. Gaines's interview with Dan Stone.

"I used to have nightmares about execution. I lived in San Francisco, just across the bay from San Quentin. Ten o'clock on Tuesdays was execution day. I wondered what this person must go through the month before, the week before, then the night before. I'd see myself, my brothers, and my friends going to that gas chamber. I'd have those nightmares over and over.

I wanted to write a story about an execution, so a colleague told me about this material that he had about a young man, who had been sent to the electric chair twice. The first time the chair failed, but a year later, he was executed. That happened in 1948, the same year that I left to go to California.

I visited small-town sheriffs and jails. I met a minister who had escorted a young man to the electric chair. The electric chair at Angola was called Gruesome Gertie. I had a lawyer in my creative writing class who had a client on death row, and I would ask him questions. I'd ask him about the size of the strap, the height and weight of the chair. The character Paul in A Lesson Before Dying is built around this student. And that's how I wrote the novel."

"Students are always asking me, 'Do you know the ending of your novel when you start writing?' And I have always used the analogy of getting on a train from San Francisco to go to New York. It takes three or four days to get there. I know some facts.... What I don't know is how the weather will be the entire trip.... I can't anticipate everything that will happen on the trip, and sometimes I don't even get to New York, but end up in Philadelphia."

—Ernest J. Gaines from "Writing A Lesson Before Dying", an essay in Mozart and Leadbelly

- A Lesson Before Dying is mostly narrated by the teacher Grant Wiggins from the first-person point of view. What important attributes does he reveal about himself in the opening chapters? What kinds of things does he conceal?

- Why hasn't Grant left Louisiana, though he says he wants nothing more than to get away? What is he trying to escape?

- Grant was educated in the 1930s, and 1942 marks his first year as a teacher. What do we know about Grant's school days, and how does this inform his own teaching methods?

- Miss Emma and Tante Lou pressure Grant to visit Jefferson in prison. Why does Grant follow their advice against his own wishes?

- Why does Grant refuse to sit down and eat in Henri Pichot's kitchen?

- Grant's girlfriend is a light-skinned Catholic mother of two who is not yet divorced. How do these differences create tension in their relationship?

- How does the radio mark a turn in Grant's relationship with Jefferson?

- Grant describes the cycle of life for black men in the South to Vivian. What is his answer to the question: "Can the cycle ever be broken?" Is the answer relevant today?

- Do you agree, as Grant says, that he can never be a hero but that Jefferson can be?

- What effect does Chapter 29—the only time in the narrative when we see Jefferson's writing—have on the reader? Why might Gaines make the choice to use Jefferson's diary to tell this part of the novel?

- How does the white deputy, Paul, contrast with other white men and women in the novel? Why is it important that Paul attends Jefferson's execution?

- Would you have been able to stand with Jefferson? Why wasn't Grant at the execution?

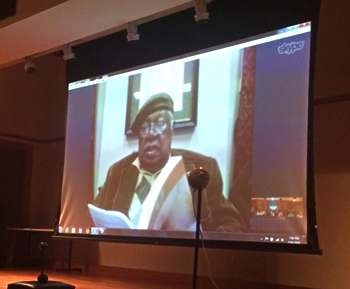

A Lesson Before Dying Author Captivates Readers in Columbus, Georgia

"We were able to get Mr. Gaines to Skype in from his home in Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana. It was, quite simply, one of the most powerful library programs we have hosted over the last several years. Mr. Gaines read the famous ‘Diary’ section of his work, and then he answered questions from our audience for another 45 minutes. Even with the technological distance we could feel and experience his warmth and grace. Audience members were quite moved by the event…many called me in the next few days to let me know how powerful an evening it was."

- from a report by the Chattahoochee Valley Library, an NEA Big Read grant recipient in FY 2015-16.