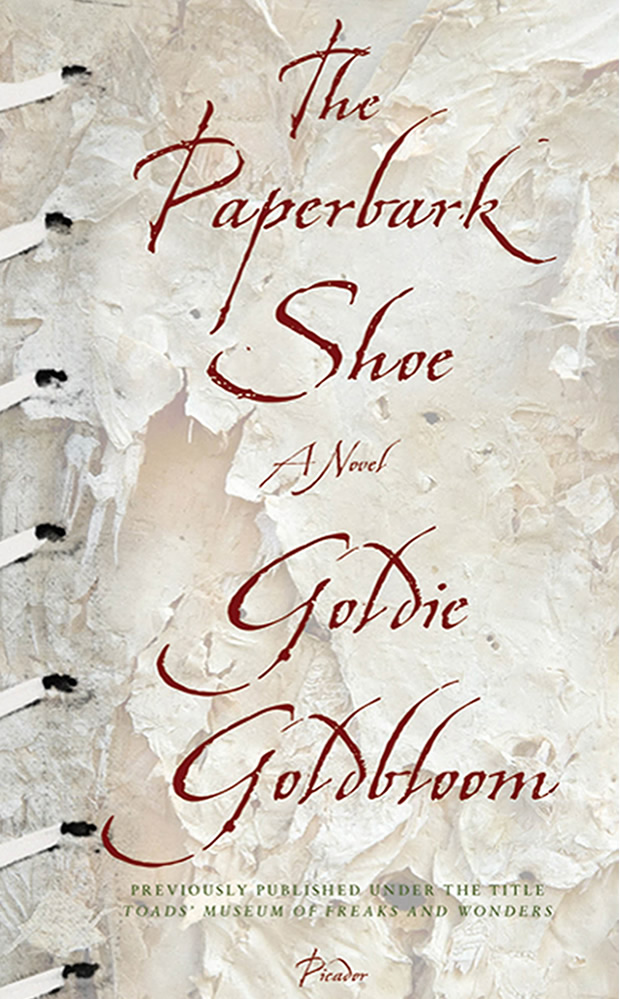

The Paperbark Shoe

OVERVIEW

Spending her early years on her family’s farm in the outback of Western Australia, Goldie Goldbloom—“an unmistakable writing talent” (Kirkus)—is the recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship and won the AWP Prize for her novel The Paperbark Shoe. Set during World War II, the novel is based on the true history of thousands of Italian prisoners of war who were sent to work the farms of Western Australia. It tells the story of a woman with albinism and a troubled past who lives with her family out in the Australian bush and falls in love with one of the Italian POWs that come to live on their farm. It’s a “masterpiece of characterization” (Good Reading Magazine). “Less gifted writers would surely veer into corny sentimentality, but chaste moments shared between the lovers are unbelievably romantic” (Newcity Lit). “The plot is consistently surprising, the ending unpredictable and the characters fully realized” (Chicago Tribune). “Extraordinary…one of the most original Australian novels I’ve read for a long time” (Sydney Morning Herald).

“We stop loving ourselves if no one loves us, Gin.” – from The Paperbark Shoe

OVERVIEW

Spending her early years on her family’s farm in the outback of Western Australia, Goldie Goldbloom—“an unmistakable writing talent” (Kirkus)—is the recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship and won the AWP Prize for her novel The Paperbark Shoe. Set during World War II, the novel is based on the true history of thousands of Italian prisoners of war who were sent to work the farms of Western Australia. It tells the story of a woman with albinism and a troubled past who lives with her family out in the Australian bush and falls in love with one of the Italian POWs that come to live on their farm. It’s a “masterpiece of characterization” (Good Reading Magazine). “Less gifted writers would surely veer into corny sentimentality, but chaste moments shared between the lovers are unbelievably romantic” (Newcity Lit). “The plot is consistently surprising, the ending unpredictable and the characters fully realized” (Chicago Tribune). “Extraordinary…one of the most original Australian novels I’ve read for a long time” (Sydney Morning Herald).

INTRODUCTION TO THE BOOK

“I have been called some terrible names in this life, but now I only hear his voice in the mouths of my tormenters, saying, ‘You are beautiful.’” – from The Paperbark Shoe

It’s 1943 and Virginia “Gin” Toad—a 30-year-old pianist from the city of Perth, Western Australia—is trying her best to make a new life in the rural farming town of Wyalkatchem out in the vast and silent Australian bush. While World War II rages in Europe, Gin and her small, odd husband Agrippas Toad (“Toad”) receive two of the many Italian prisoners of war sent to Australia during that time to provide much needed farm labor. Antonio and John settle in over several months. They build their own lodging, feed the calves and harvest the wheat, sing and tell stories of back home, entertain Gin and Toad’s two children, and bring joy to Gin and Toad in unexpected ways. In stark contrast to her distrusting neighbors and a dark past, Gin finds herself feeling love and desire for the first time. But it can’t last. Secrets and their accompanying feelings of shame and guilt and longing begin to surface as the reality of war comes back to invade and unravel their isolated lives.

At the time Antonio and John arrive, Gin is pregnant with her fourth child. Mudsey, her daughter, is the eyes and ears of the household, missing nothing as she runs about in her sundress, a former feed sack that’s bleached and tied with a leather string. She and her younger brother Alf like to hide under the house with their collection of “magpie eggs, gumnuts, sheep’s knucklebones” and a mouse’s skeleton “laid out in a matchbox coffin” (p. 28). Gin, meanwhile, is haunted by the memory of her second daughter, Joan, who died of diphtheria. Unlike Mudsey and Alf who look more like Toad, Joan had albinism like Gin, a rare condition shrouded at the time in harsh and often damaging superstitions and myths.

Involuntarily committed to a mental hospital in Perth years earlier by her abusive stepfather, Gin had played the piano to steady herself. One day Toad walked into the hospital and, lured by her music and the need for a wife, asked her to marry him. He took her back to Wyalkatchem where he grew up, a town with a population of 68 adults and 43 children “counting the ones in the cemetery” (p. 14). Often the butt of jokes, Toad has a crass sense of humor and a penchant for Victorian corsetry. He can gargle his “after-dinner port to the tune of Waltzing Matilda” (p. 18). But he has a tender side that comes through in his paintings drawn on the walls of their outhouse that illuminate, according to Gin, “our deepest longings, our secret wishes for home and love and power and escape….” (p. 83). “Despite his squat physiognomy and prickly personality, [Toad] emerges as one of the book’s most emotionally accessible characters” (Huffington Post).

“There was an attitude in Australia amongst earlier generations that you just did,” explains Goldbloom. “You did and did and did until you died. I grew up with a hang-over of that attitude, a part of me that avoids complaining, that thinks of wearing goggles at the pool as an affectation of wusses and sunglasses as the devil’s spawn. As a child I saw some amazingly ill-matched couples who, nevertheless, worked together, raised families, rarely argued, just got on with it. I suppose you could say that the glue that held [Toad and Gin] together was simply the ‘isness’ of them.” (BookBrowse).

The arrival of the two Italian POWS turns that “isness” on its head. John, the younger of the two, is “tiny, nervous, pacing sideways, shaking his glossy mane, a racehorse of a man” (p. 16). He and Toad form an immediate bond. The older and larger Italian, Antonio Cesarini, is a 40-year-old shoemaker from the Italian village of Sant’Anna where his beloved wife and five children still remain. “Fastidious they were, in everything: their clothes, their bodies, their rooms, everything washed and groomed every day and reeking of otherness,” Gin tells us (p. 76).

As part of her research for the novel, Goldbloom wrote to the Australian National Archives about the prisoners of war who worked on her grandparents’ farm. “The documents they sent me included copies of the men’s work books, which had such personal information as who they were married to, the names of their children, what work they had done before being drafted, and where they lived in Italy…. Suddenly, those men weren’t old stories told around the campfire. They were real people caught up in a war and sent to a country not their own. And yet their real lives, for the most part, remained hidden from the Australians they worked for. I was fascinated with the disconnect between what was seen and what was not seen, not just with the Italian characters, but of course with Gin and Toad, and their children, too. In the novel, there is a constant peeling back of external layers that reflects my interest in secrets and hiddenness and internal worlds” (My Jewish Learning).

In the novel, Antonio and Gin share a love of opera and sometimes after dinner they sing music by Giacomo Puccini, Amilcare Ponchielli, and from Giuseppe Verdi’s La Traviata. He crafts shoes for Gin’s family and Gin sews clothes for his children. Antonio senses Gin’s pain and fragility and responds with gentleness and sensual affection, which she interprets as love. Shortly after she witnesses something shocking by the riverbank, she allows herself to return Antonio’s affection. But a drought is coming. Gin will encounter an Australian soldier she knew from Perth who will discover what is going on between her and the Italian prisoner of war. She will give birth and shock her community as they gather to watch and be amazed by the new movie The Wizard of Oz. And eventually, as secrets are hurled out into the open and tragedy strikes, the movie’s mantra will forever linger in the eerie silence of the outback: “There is no place like home.”

Goldie Goldbloom’s Music Playlist to Accompany The Paperbark Shoe

-

Erik Satie - Embryons desséchés, II. D'Edriophthalma. Sombre

-

Giuseppe Verdi - Nabucco: “Va, pensiero” (Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves)

-

Frédéric Chopin – “Raindrop” Prelude, Op 28, No. 15

-

Maurice Ravel - Pavane pour une infante défunte

-

Giuseppe Verdi with Maria Callas - La traviata

-

Giacomo Puccini – “O mio babbino caro”

-

Samuel Barber - Adagio for the Strings

-

Harold Arlen and E.Y. Harburg – “We're Off to See the Wizard” from The Wizard of Oz

-

Jacques Offenbach - Barcarolle from The Tales of Hoffmann

-

Bedřich Smetana - The Moldau from Má vlas

-

Ludwig van Beethoven - Piano Sonato No. 29, Opus 106 (“Hammerklavier”)

-

Slainte – “The Star of the County Down”

-

Glenn Miller – “In the Mood”

-

Vera Lynn – “We'll Meet Again”

-

Giacomo Puccini – “Che gelida manina” from La bohème

-

Giuseppe Verdi – “La donna è mobile” from Rigoletto

-

Erik Satie – “Gymnopédie No. 1”

-

Giovanna Daffini –“Bella Ciao”

-

“Maria Lavava” – an Italian nursey rhyme

-

Giacomo Puccini – “Coro a bocca chiusa” from Madama Butterfly

-

Frances Langford – “I'm in the Mood for Love”

-

John McCormack – “It's a Long Way to Tipperary”

-

The Clancy Brothers & Tommy Makem – “The Wild Colonial Boy”

NEA Big Read Author Goldie Goldbloom on Bullying, Writing in the Bathtub, and Books (Art Works Blog, 3/19/2019)

-

The Paperbark Shoe takes place on a remote farm near a small town in Western Australia. Are you familiar with this setting? Were there particular descriptions of the landscape that surprised you? Did you find the Australian bush to be a “lonely kind of a place” (p. 96)?

-

The story also takes place in 1943 and illuminates a piece of World War II history in which thousands of Italian prisoners of war were sent to Western Australia unguarded to help on the farms. Were you aware of this history? How would you describe some of the cultural differences in the story between the Italians and the Australians of Wyalkatchem?

-

The novel is written almost entirely in Gin’s voice and from her point of view. Did it strike you at some point in the story that she may be an unreliable narrator, i.e., someone who misrepresents—either deliberately or unknowingly—what’s really going on? If so, when? Why do you think an author chooses to tell a story from the perspective of a character who misrepresents reality? Why do you think Goldbloom included brief passages in an omniscient voice (e.g., beginning of part two, p. 135)?

-

Gin admits that she has not been a good mother and is often filled with regret. Were there instances in which you found yourself reacting more negatively to her behavior as a parent? Were there instances in which you felt more sympathetic to her given her circumstances? Do you think she would have been a better mother to Mudsey and Alf if Joan had lived?

-

How did Gin’s condition of albinism affect her physically and emotionally? What were some of the superstitions that surfaced in the story about people with albinism? What impact did they have on Gin’s self-image? In what ways did her condition contribute to her attitude toward being touched?

-

What do you make of Toad? What aspects of his personality and circumstances elicit your anger? Pity? Admiration? Understanding? How would you describe Gin’s feelings towards him?

-

Would you describe Antonio’s actions and words with regard to Gin—including his nickname for her—as honest or deceitful? Why?

-

“Stories show a little of what we are,” says Gin when she, Toad, Antonio, and John are sitting around a campfire by Moore River (p. 117). What does each story in this chapter reveal about the one who’s telling it? Are there other moments in the book in which a shared story or anecdote reveals something about the storyteller?

-

After Gin sees Toad down by the river with John (p. 128), she feels a surge of mixed emotions: anger, envy, shame, compassion, abandonment. Would she have been better off not seeing what she saw? Why or why not? What would have changed—for better or worse—had she not witnessed that scene?

-

What is the relationship in this story between feeling love and feeling loved? Can you think of instances in which love is mistaken for pity and/or desire? Are there instances in which the absence of love leads a character to act against his or her better judgment? Do you agree with Antonio when he tells Gin she has “no idea what love is”? (p. 340)

-

Authors make deliberate decisions about when to divulge information and/or secrets about their characters throughout their narratives. Can you think of some examples of secrets that were revealed at the beginning of the novel? At the end? How about at other heightened moments in the story? Why do you think Goldbloom chose these particular moments for such revelations?

-

Toad identifies with a home that doesn’t accept him. Antonio identifies with a home that he loves but is far away and in jeopardy. Gin feels like she’s without a home and longs for one that doesn’t exist. If you had to choose among these fates, which would you choose? How does each character’s idea of home affect their attitudes and actions? What is your idea of home? How do you think it affects your attitudes and actions?

-

Do you think Gin actually made it to Italy? What did she learn there—about Antonio, about war, about herself? In what ways has she changed by the end of the novel?

-

While much of The Paperbark Shoe is fictional, it is based on actual historical events—such as the bombing of Darwin, the POW outbreak at Cowra, and the massacre at Sant’Anna. What effect did this weaving together of fiction and nonfiction elements have on your reading of the novel? How might historical fiction help us understand actual events in different and/or deeper ways than historical nonfiction?