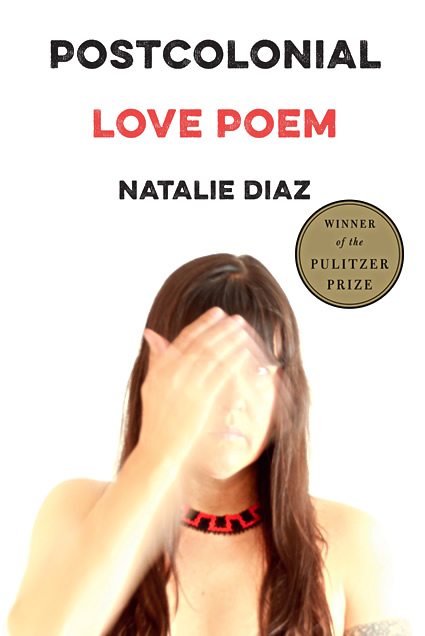

Postcolonial Love Poem

Overview

A finalist for the 2020 National Book Award for Poetry and winner of the 2021 American Book Award and Pulitzer Prize in Poetry, Postcolonial Love Poem is the “exquisite, electrifying” (Publisher’s Weekly) second collection from Mojave American poet, educator, MacArthur fellow, and language activist Natalie Diaz. “In a world where nothing feels so conservative as a love poem, Diaz takes the form and smashes it to smithereens, building something all her own” (LitHub). In doing so, Diaz claims the autonomy of desire, countering the violent erasure of indigenous imagination. “No doubt one of the most important poetry releases in years” (New York Times Book Review). “With tenacious wit, ardor, and something I can only call magnificence, Diaz speaks of the consuming need we have for one another,” writes Louise Erdrich. “This is a book for any time, but especially a book for this time…. Be prepared to journey down a wild river.”

“Americans prefer a magical red Indian, or a shaman, or a fake Indian in a red dress, over a real Native. Even a real Native carrying the dangerous and heavy blues of a river in her body.” — Postcolonial Love Poem

In her second collection, Postcolonial Love Poem (Graywolf Press), Natalie Diaz locates the body not simply in flesh and bone, but in land, water, myth, ritual, memory, in the space beyond language and speech. Divided into three sections, the collection spans generations, geography, and poetic form, refusing the imposition of a linear history or singular identity. Each section begins with a quote from a different poet—the words of Joy Harjo, Mahmoud Darwish, Hortense Spillers, Robyn Fenty, and Sor Juan Inés De La Cruz all make an appearance—and their voices add to the many tensions throughout the poems. “This book asks us to read the world carefully, knowing that not everything will be translated for us, knowing that it is made up of pluralities” (New York Times).

Born and raised on the banks of the Colorado River—whose currents run through the collection—Diaz offers loving tribute to the many bodies of water, land, legend, and language that make up self and community, expanding the exploration of love that animated her debut collection, When My Brother Was an Aztec. “Our imagination is prisoner to no one and obeys no borders,” Diaz wrote in 2017, in an essay for the Los Angeles Review of Books. “To create is also an act of love. Love, like art, is not subject to control or governance—they are two of the purest forms of potential.” In her deft hands, love is rendered as thirst, anger, absence, refusal, grace, the hips of a lover, the arc of a basketball. Language, too, transmutes from tenderness to harm and back again. “The first violence against any body of water / Is to forget the name its creators first called it. / Worse: forget the bodies who spoke that name,” (p. 64) she writes in the poem “exhibits from The American Water Museum.” Translation and legibility are exposed as tools of violence and occupation. History is deception, and myth reveals truth.

In the last pages of Postcolonial Love Poem, Diaz dedicates the collection “toward,” rather than “to” a community of loved ones, a refrain of the idea that we and our beloveds are bodies in momentum; that love and art engage in a cycle of return. “When we create, we invoke the body, our own and every body that came before us—against erasure, against massacre, against imprisonment, against illness, against forgetfulness,” Diaz wrote in the Los Angeles Review of Books. “When we image these bodies in our work, we are imaging our homelands.”

- The first poem of the book shares the collection’s title: “Postcolonial Love Poem.” What did each of these words mean to you before you read this collection? Before you read the poem? Did their meanings shift for you once you finished the book?

- Though the first poem in the collection is the only one labeled as a love poem, were there other poems that you felt could be described as love poems? If so, why?

- Across the collection, Diaz uses the word “river” as a noun, but also as a verb (“…we are rivered. / We are rearranged” p. 93), and in one poem, as an interactive performance piece (p. 63). What do you make of these different uses of the word?

- In the poems “Run’n’Gun,” “The Mustangs,” and “Top Ten Reasons Why Indians Are Good at Basketball,” Diaz writes about basketball and its importance in her own life and for her loved ones: a game with “the power to quiet what seemed so loud in us” (p. 36). Did reading these poems make you think about basketball in a new way? Can you think of a time in your own life when something had the power to “quiet what seemed loud” in you?

- In an interview with the Rumpus shortly after the publication of Postcolonial Love Poem, Diaz described language as “a mere wish of meaning.” “Language is not my body,” she said. “Rather it is an estimation or an intimation of my body, of what my body hopes of itself, of how my body is related to you and your body, to all non-human bodies. It also moves and shifts—what I intend of a word, phrase, or line ultimately abandons me and becomes loyal to the reader instead, becomes the reader’s own creation.” Have you ever felt like something you wrote or said “abandoned” you, or became someone else’s creation?

- In the poem “American Arithmetic,” Diaz uses statistics from Department of Justice reports to show the ways in which numbers and census data remove people from narratives of place or nation. “Native Americans make up less than / 1 percent of the population of America. / 0.8 of 100 percent…We are Americans, and we are less than 1 percent / Of Americans. We do a better job of dying / By police than we do existing” (p. 17). Think about statistics that you encounter in your own life: in school, in the news, in books. Why are statistics used as a source of information so often? What is missing from those numbers? Who is missing? How might Diaz be challenging ideas of trust or trustworthiness in information?

- The poem “The First Water is the Body” includes one of the few moments in which Diaz writes in the Mojave language, which she translates into English and then states, “This is a poor translation, like all translations” (p. 46). How do you understand this line? What might be lost during the process of translation?

- Throughout the collection, various fables and mythologies animate Diaz’s poetry: from the Minotaur in “I, Minotaur” to Noah’s ark in “It Was the Animals,” to the orchard of Alcinous in “Ode to the Beloved’s Hips.” Were you familiar with any of these stories before reading these poems? If so, did that affect your engagement with the poems? In what ways?

- During an interview with Rigoberto Gonzalez for the National Book Critics Circle, Diaz said of her relationship to myth: “Even though most people use the word ‘myth’ to speak of our tribal stories, we see them as truth. So, for me, myth has always been the truest truth. The word ’history’ on the other hand, we question.” How have you understood the words “myth” and “history” in the past? What histories are questioned throughout Postcolonial Love Poem? What histories are you interested in questioning?

- Across the collection, there are four poems that share the word “Light” in their title: “Blood-Light,” “Skin-Light,” “Ink-Light,” and “Snake-Light.” What sources of light are depicted in each of these poems? Did you find them to be expected or unexpected? In what ways?

- In the poem “exhibits fromThe American Water Museum,” Diaz sets America’s relationship to water in the framework of a museum: “recordings” (p. 63), a “dilapidated diorama” (p. 65), “marginalia” (p. 66), places and people that populate the exhibits of the museum. How does this poem tie into the collection's broader themes of environmental harm and colonialism?

- Museums appear across a number of Diaz’s poems. Think about museums that you have visited. What was on display there? Whose stories were being told? Who was doing the storytelling?

- Postcolonial Love Poem includes two poems bookending three sections, each separated by a quote from a different poet: Joy Harjo, Mahmoud Darwish, Hortense Spillers, Robyn Fenty (better known by her middle name, Rihanna), and Sor Juan Inés De La Cruz. How did the presence of these quotes affect your experience of the collection? Did any of the quotes surprise you?

- In the poem “Cranes, Mafiosos, and a Polaroid Camera,” Diaz describes a call from her brother: “It was 3:24 a.m. / It’s me, he said. It’s your brother. He had taken apart / Another Polaroid camera and needed me to explain how / To put it back together…I should know how to help my brother by now. / He and I / Have had this exact conversation before—if I love him, / If I really love him, why haven’t I learned to reassemble / A Polaroid camera?” Have you ever experienced a time when you wanted to help someone you loved but didn’t know how?

- The poem “Manhattan Is a Lenape Word” ends with the line “Am I / what I love? Is this the glittering world / I’ve been begging for?” (p. 16) In the closing notes of the collection, Diaz explains that the “glittering world” of the poem is one way the Mojave creation story has been translated: “since the earth was still wet so rocks and dirt gleamed” (p. 97). In your own culture and community, are there any creation or origin stories that have been passed down? How have they shaped you today?