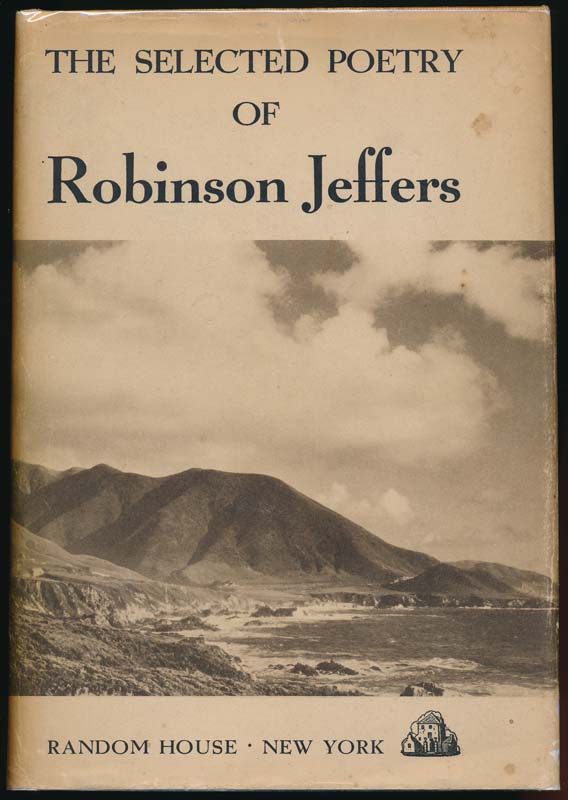

Selected Poetry

Overview

The poetry of Robinson Jeffers is emotionally direct, magnificently musical, and philosophically profound. No one has ever written more powerfully about the natural beauty of the American West. Determined to write a truthful poetry purged of ephemeral things, Jeffers cultivated a style at once lyrical, tough-minded, and timeless.

"Permanent things, or things forever renewed, like the grass and human passions, are the material for poetry..." —from his essay "Poetry, Gongorism and a Thousand Years" (1948)

Overview

The poetry of Robinson Jeffers is emotionally direct, magnificently musical, and philosophically profound. No one has ever written more powerfully about the natural beauty of the American West. Determined to write a truthful poetry purged of ephemeral things, Jeffers cultivated a style at once lyrical, tough-minded, and timeless.

Introduction to Robinson Jeffers' Poetry

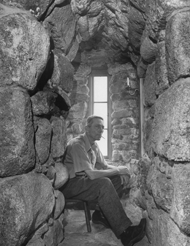

The poetry of Robinson Jeffers is distractingly memorable, not only for its strong music, but also for the hard edge of its wisdom. His verse, especially the wild, expansive narratives that made him famous in the 1920s, does not fit into the conventional definitions of modern American poetry. Scarcely stirring from Carmel, California, Jeffers wrote about ideas: big, naked, howling ideas that no reader can miss. The directness and clarity of Jeffers’s style reflects the priority he put on communicating his worldview.

He challenged scientists on their own territory. Unlike most writers, he had studied science seriously in college and graduate school. He accepted the destruction of anthropocentric values explicit in current biology, geology, and physics. Jeffers concentrated on articulating the moral, philosophical, and imaginative implications of those discoveries. He struggled to answer the questions that science had been able only to ask: What are man’s responsibilities in a world not made solely for him? How does humankind lead a good and meaningful life without a Providential God?

Standing apart from the world, he passed dispassionate judgment on his race and civilization, and he found them wanting. Pointing out some grievous contradictions at the core of Western industrial society earned Jeffers a reputation as a bitter misanthrope (he sometimes was) but this verdict hardly invalidates the essential accuracy of his message. He saw the pollution of the environment, the destruction of other species, the squandering of natural resources, the recurrent urge to war, and the violent squalor of cities as the inevitable result of a species out of harmony with its own world.

What saves Jeffers’s poetry from unrelieved bitterness and nihilism is its joyful awe and indeed religious devotion to the natural world. Living on the edge of the Pacific, he found wisdom, strength, and perspective from observing the forces of nature around him. Magnificent, troubling, idiosyncratic, and uneven, Jeffers remains the great prophetic voice of American modernism.

Lyric Poetry

During Jeffers’s life, the controversies about his narrative poems unfortunately overshadowed the shorter works tucked into the back pages of each new book. These lyric meditations—often autobiographical and generally written in long, rhythmic free-verse lines—marked a new kind of nature poem that tried to understand the physical world not from a human perspective but on its own terms. He rejected rhyme and traditional meter, which inhibited him from telling a story flexibly in verse. Disclaiming the example of Walt Whitman, Jeffers preferred—as scholar Albert Gelpi explains—“to see the long verses of the Hebrew prophets and psalmists in the King James translation or the hexameters of Homer and Aeschylus as more kindred analogues and sources.”

To say that Jeffers’s chief imaginative gifts were scope, simplicity, narrative poise, and moral seriousness makes him seem closer to a distinguished jurist than a great poet. But there was something of the judge about Jeffers, particularly the Old Testament variety. In such poems as “Shine, Perishing Republic,” Jeffers warns corrupt humanity against the evils of war and violence. His belief that mankind is not the center of the universe is expressed in poems like “Credo”: “The beauty of things was born before eyes and sufficient to itself; the heart-breaking beauty / Will remain when there is no heart to break for it.” When he is gone, he prays—in the poem “Granddaughter”—that his beloved little Una “will find / Powerful protection and a man like a hawk to cover her.”

Although Jeffers knew that he and his sons would die and that the world as they knew it would change, he predicted that “this rock will be here, grave, earnest, / not passive” in his poem “Oh Lovely Rock.” As Jeffers believed, man might be “nature dreaming,” but through hawks, stones, and the ocean, “The Beauty of Things” will endure: “to feel / Greatly, and understand greatly, and express greatly, the natural / Beauty, is the sole business of poetry.”

Narrative Poetry

While Jeffers devoted considerable attention to the lyric form throughout his career, his decision to write narrative poetry led him to the epic tradition and verse drama. From 1925 to 1954, Jeffers wrote the most stunning, ambitious, and stylistically diverse series of narrative poems in American literature. Originally published in fourteen major collections, these books add up to more than 15,000 pages of verse.

Jeffers’s epic-length poems such as Tamar, The Women at Point Sur, Cawdor, Thurso’s Landing, and The Loving Shepherdess told the mostly tragic stories of men and women who lived on the Big Sur Coast of California. His verse dramas such as The Tower Beyond Tragedy, Dear Judas, At the Beginning of an Age, Medea, and The Cretan Woman turned to ancient Greece, the Bible, and medieval Europe for inspiration. In both instances, Jeffers used traditional genres, subjects, and themes to interrogate the Western tradition as a whole and to illuminate modern life.

His concern with the latter compelled him to look closely at American culture and the surrounding world. He was usually repelled by what he saw. Identifying “cruelty and filth and superstition” as the three banes of humankind, Jeffers lashed out at the horrific violence of the two World Wars, at the pollution destroying wildlife and ruining natural environments, and at the political and religious fanaticism darkening the minds of millions.

Almost immediately Jeffers’s long narrative poems divided audiences. Violent, sexual, philosophical, and subversive, these verse novels are alternately magnificent and hyperbolic, powerful and excessive, dramatic and overblown, and unlike anything else in modernist American poetry.

- Robinson Jeffers studied literature, philosophy, medicine, and forestry in graduate school. How do these four areas of study inform the subject matter and style of Jeffers’s poetry?

- Jeffers and his wife, Una, discovered the coast of Carmel to be their “inevitable place.” How does this landscape inform his poetry? Where is your “inevitable place”?

- What parallels can you imagine between the building of a stone house and the writing of a poem? Can you find examples of this parallel in Jeffers’s poetry?

- Many mammals and birds—especially the red-tailed hawk and the falcon—appear in Jeffers’s poetry. While his allusions to animals are certainly literal, what symbolic possibilities exist in poems such as “Rock and Hawk” or “Hurt Hawks”?

- In his poem “Carmel Point,” Jeffers declares that “people are a tide / That swells and in time will ebb, and all / Their works dissolve.” How poignant is the parallel Jeffers makes between the human race and the tide?