The Shawl

Overview

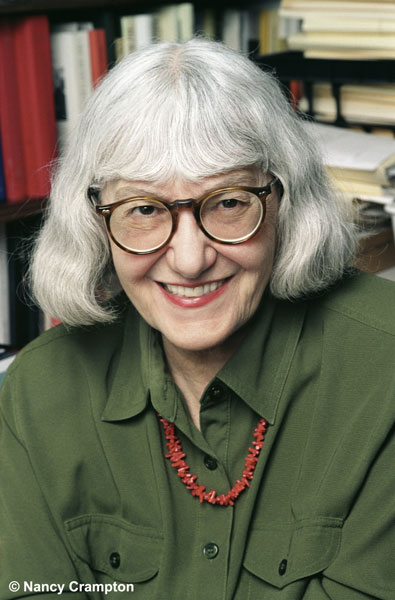

“Considered one of the greatest fiction writers and critics alive today” (The New York Times), award-winning author Cynthia Ozick received a National Endowment for the Arts creative writing fellowship in 1968 at the age of 40, two years after she published her first novel. She was raised in the Bronx at a time when it was, according to Ozick, “semi-rural,” helping to deliver prescriptions for her parents, owners of the local pharmacy. Published in 1989, The Shawl includes two of her most well-known stories, originally published in The New Yorker and included in the annual Best American Short Stories and awarded first prize in the annual O. Henry Prize Stories collection. In the first story, a woman, her niece, and her daughter struggle to survive in a Nazi concentration camp. The second finds the woman and her niece 30 years older, one trying to remember the past and the other trying to forget. “Beautiful and harrowing, these stories are a masterly achievement” (Wall Street Journal). They are “brilliant miniatures,” writes The Philadelphia Inquirer, “rich with passion and compassion. They call to be read again and again.”

"Just as you can’t grasp anything without an opposable thumb, you can’t write anything without the aid of metaphor. Metaphor is the mind’s opposable thumb." —from a 1998 Atlantic Monthly interview

Overview

“Considered one of the greatest fiction writers and critics alive today” (The New York Times), award-winning author Cynthia Ozick received a National Endowment for the Arts creative writing fellowship in 1968 at the age of 40, two years after she published her first novel. She was raised in the Bronx at a time when it was, according to Ozick, “semi-rural,” helping to deliver prescriptions for her parents, owners of the local pharmacy. Published in 1989, The Shawl includes two of her most well-known stories, originally published in The New Yorker and included in the annual Best American Short Stories and awarded first prize in the annual O. Henry Prize Stories collection. In the first story, a woman, her niece, and her daughter struggle to survive in a Nazi concentration camp. The second finds the woman and her niece 30 years older, one trying to remember the past and the other trying to forget. “Beautiful and harrowing, these stories are a masterly achievement” (Wall Street Journal). They are “brilliant miniatures,” writes The Philadelphia Inquirer, “rich with passion and compassion. They call to be read again and again.”

This title is no longer available for programming after the 2017-18 grant year.

Introduction to the Book

Readers should not be fooled by the slimness of Cynthia Ozick's award-winning book The Shawl (1989). The interlocking short story and novella pack enough punch for a book many times its length. Though set several decades apart and on opposite sides of the Atlantic, the two sections describe with heart-breaking empathy the life of one woman.

The title story, "The Shawl," introduces us to Rosa, the mother of a baby girl hidden within a tattered cloth, and her fourteen-year-old niece, Stella, as they attempt to survive the horrors of life in a Nazi death camp. Cold, exhausted, starving, they live in "a place without pity" where the struggle for the most basic necessities can have terrible consequences. When Stella warms herself with the shawl, she unwittingly begins a chain of events that leads to her infant cousin's death.

In the novella, set almost four decades later, Rosa and Stella are refugees in America. Though they left Poland long ago, neither can escape memories of the Holocaust. Stella copes by attempting to forget and build a new life in New York; Rosa cannot. Unable to relinquish the past, Rosa destroys her New York store and moves to a cheap Miami hotel. Adrift in a world without companionship, Rosa relies on financial support from her niece.

In spite of her pain, Rosa makes fumbling attempts to tell the story of her suffering, to warn others of man's capacity for unspeakable evil. In Simon Persky—a flirtatious, retired button-maker—Rosa finds a willing listener and perhaps someone who can understand the hurt that can never, and should never, be forgotten.

Full of beautiful imagery and finely crafted sentences, The Shawl is a tour de force that portrays not only the characters' grief, guilt, and loneliness but also their hopes and dreams. It's a novel about the importance of remembering, of bearing witness, and of listening to the lessons of history with our ears and our hearts.

Major Characters in the Book

Rosa Lublin

As a young woman, Rosa is raped by a German soldier, confined in the Warsaw Ghetto, and sent to a Nazi concentration camp in German-occupied Poland with her niece, Stella, and her infant daughter, Magda. Almost four decades later, Rosa lives in Miami, haunted by the memory of her daughter's death. "Rosa Lublin, a madwoman and a scavenger, gave up her store—she smashed it up herself—and moved to Miami. It was a mad thing to do. ... Her niece in New York sent her money and she lived among the elderly, in a dark hole, a single room in a 'hotel.'"

Stella

Teenage Stella's theft of the shawl leads to her cousin Magda's death. As an adult, Stella provides Rosa with financial support, but she cannot understand her aunt's inability to let go of the past. "Stella liked everything from Rosa's junkshop, everything used, old, lacy with other people's history."

Magda

A baby hidden in her mother's shawl, Magda survives infancy in a concentration camp in Nazi German-occupied Poland but is murdered by a guard at fifteen months old.

"The face, very round, a pocket mirror of a face: but it was not Rosa's bleak complexion, dark like cholera, it was another kind of face altogether, eyes blue as air, smooth feathers of hair nearly as yellow as the Star sewn into Rosa's coat. You could think she was one of their babies."

Simon Persky

A retiree whose wife is hospitalized in a mental institution, Simon is a comic character in a tragic situation. His persistent kindness begins to break through some of Rosa's barriers. "Two whole long rows of glinting dentures smiled at her; he was proud to be a flirt."

How The Shawl Came to Be Written

"The Shawl began with a line, one sentence in The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich by William Shirer. This one sentence told of a real event, about a baby being thrown against an electrified fence. And that stayed with me and stayed with me, and that was the very explicit origin of The Shawl."

"It began with those very short five pages. We read now and again that a person sits down to write and there's a sense that some mystical hand is guiding you and you're not writing out of yourself. I think reasonably, if you're a rational person, you can't accept that. But I did have the sense—I did this one time in my life—that I was suddenly extraordinarily fluent, and I'm never fluent. I wrote those five pages as if I heard a voice. In a sense, I have no entitlement to this part because it's an experience in a death camp. I was not there. I did not experience it."

"I wrote the second half because I wanted to know what happened to Rosa afterward. I was curious to enter the mind of such an unhappy, traumatized person and see how that person would cope with the time afterward—rescued, saved, safe, and yet not rescued, not safe, not normal, abnormal."

—Excerpted from Cynthia Ozick's interview with former NEA Chairman Dana Gioia

- After witnessing Magda's murder, Rosa shoves the shawl in her own mouth to stifle her scream rather than make a sound and risk being shot by the camp guards. What does this scene reveal about Rosa? How does this scene repeat later in the novella?

- Do you agree with Cynthia Ozick's interpretation that Stella is "an equal victim with Rosa" and that "Stella has become a ghost or a phantom of all of Rosa's fears and terrible traumatic memories?"

- Why is Rosa so upset when she loses her underwear at the laundromat? Do you find the situation humorous? Why or why not?

- Why does Rosa decide to trust Simon Persky? Is his occupation significant to his character?

- What does Rosa mean when she tells Persky, "Your Warsaw isn't my Warsaw." How are their backgrounds different? How are they similar?

- How does Stella's life mirror Rosa's? How is it different? What does this suggest about their relationship?

- What role does Dr. Tree play in the novella? Are there people today who might act like Dr. Tree? Can you sympathize with Rosa's hatred for him?

- Why does Rosa reject labels like "survivor" and "refugee" in favor of "human being?"

- What does the shawl symbolize to Rosa? To Magda? To Stella?

- Discuss some Jewish symbols and imagery in the novella. How might these demonstrate that—even thirty-nine years later—Rosa's thoughts are never far from the concentration camp?

- In your experience, does the book reinforce or shatter stereotypes of Jewish American experience? Why or why not?

- By telling the story of Magda's death and of Rosa's survival, what does the book reveal about Rosa's personality and her will to live?

The Shawl Inspires Deep Engagement in Poughkeepsie, New York

“There was some resistance to the choice of book and addressing the themes of the Holocaust for four weeks was challenging. However, this Big Read connected with the public at a deeper level than any before. We credited this to the significant amount of first-person testimonies and to the intentional thoughtfulness of our scholars, our guests, our artists, our teachers, our librarians. Reflecting on this particular piece of literature brought us to reflections on the particular period of history and to the stories of our neighbors, told in poetry, photography, film, literature, onstage and in first-person telling. The survivors, the hidden children, the documentaries and the music offered very compelling accounts that moved local residents of all ages.”

|

– from a report by the Poughkeepsie Public Library District, an NEA Big Read grant recipient in FY 2013-2014.

The Shawl Prompts Holocaust Survivors to Share Their Stories in Snow Hill, Maryland

“Marcel Drimmer who survived the Holocaust as a boy spoke to a full house about his experiences. He traveled to us from Washington, DC to share his past with us. His story was breathtaking and it is a miracle that he survived. Members of the audience praised Marcel for his bravery and for his perspective on life now that he is 77 years old. Marcel explained that he does not hate. Hatred is what caused the Holocaust. He stated that he would not allow his childhood to ruin the rest of his life and he led a full productive life as an engineer. He learned to put his memories in a place and leave them there so he could live his life to the fullest. He was emotional and it was evident that what he has tried to do has been effective to some extent but left unimaginable scars. These two first programs really provided participants with questions, comments, and answers to issues raised by the book, The Shawl. The highlight of the series was the camaraderie of the participants. There were many Jewish participants and they felt as if they and their ancestors were being “honored” by us choosing The Shawl for our Big Read. There were many tears as people shared their own stories and the stories of their loved ones.”

– from a report by the Worcester County Library, an NEA Big Read grant recipient in FY 2009-2010.