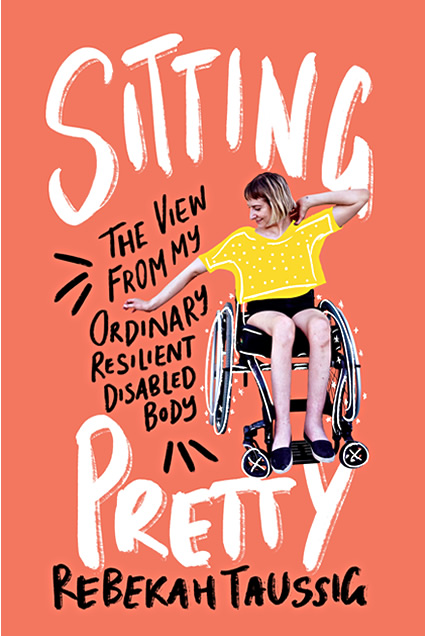

Sitting Pretty: The View from My Ordinary Resilient Disabled Body

Overview

Born in Manhattan, Kansas, in the mid-1980s, Rebekah Taussig was 14 months old when she was diagnosed with a malignant cancer that attacked her spine. Two years of intense treatment left her cancer-free but paralyzed from the waist down. As a young girl, she searched for nuanced depictions of disability: stories that captured all the ways disability could be complex and ordinary, uncomfortable and fine, painful and fulfilling. As an adult, she created her own. Taussig’s Sitting Pretty is a “memoir-in-essays” spanning personal stories and family histories, offering “a fierce and fabulous revision to entrenched ableist scripts” (Kirkus Reviews) through “spunky, self-aware wit, combined with education that never feels didactic” (speaker and disability rights activist Emily Ladau). “Taussig’s explorations of the ways her own ordinary, resilient, disabled body interacts with a largely able-bodied world are complex, evading neatly tied conclusions and categories” (Rumpus). “Part wake-up call, part call-to-action, this [book] will resonate with anyone who lives in a body, disabled and nondisabled alike” (LitHub).

“This is the wild emancipation I wish for all of us—a world where we are all free to be, to move, to exist in our bodies without shame; a world that isn’t interested in making all of its humans operate in the exact same way; a world that instead strives to invite more, include more, imagine more.” — from the essay “What’s the Problem”

Growing up as a paralyzed girl in the 1990s and early 2000s, Rebekah Taussig rarely encountered complex depictions of disability. The stories told on screens, through ads, and in magazine pictures all centered a particular kind of body and perspective—one that pushed all others to the margins.It wasn't until her 20s that she found a new lens through which to see the world around her. Through education and getting to know the disabled community, she found the stories that she'd hungered for as a child. She knew she wanted to recreate that transformation for others, combating the erasure of disability stories and allowing people to dream of a new world with more ease, more creativity, and more flexibility and resilience.

Sitting Pretty processes a lifetime of memories to paint a beautiful, nuanced portrait of a body that looks and moves differently than most. Through a series of thoughtful, conversational essays, Taussig interrogates conceptions of kindness and charity, dependence and independence. She grapples with the myth of ableism and the concept of feminism, chronicles the impossibilities of finding accessible affordable housing, and celebrates the many dimensions of an identity formed through community, self-exploration, affinity, and partnership. Taussig does not create easy narratives or singular representations of the disability community. Instead, she offers her story as one voice in the rich, expansive, and complex tapestry of human experience. In doing so, she emphasizes the importance of more stories and more perspectives to enrich our understanding of the world and our place in it.

Taussig first began exploring these ideas on her Instagram account, @sitting_pretty, and her essay collection blooms with visual and textural descriptions. In using colloquial and sensory language, she brings disability studies from the gated spaces of academia to broader audiences. This breaking down of barriers exists across her work: in and beyond the collection. “I think that we often think of our bodies in really distinct categories, disabled and not disabled and that there’s a big chasm between those groups of people,” she shared on the National Endowment for the Arts Art Works podcast. “And in some ways there are things that are distinct about our individual experiences, but a lot of what I am trying to play with and show in the book is that we all live in bodies with limitations and points of access. This is something that we all should be thinking about, and not just in a dreadful way but in a way that allows us to imagine more for each other.”

- In the first essay of Sitting Pretty, “What’s the Problem?”, Taussig explores the complexity of the word “ableism” and the ways in which it “seems to shut off curiosity—it sounds familiar enough that we’re confident we already, pretty much, understand it” (p. 8). How would you have defined ableism before you read this book? Did that definition change for you as you read? What was important in your original understanding of ableism? What was missing from it?

- In the same essay, Taussig writes about her older brother, David. Despite growing up beside each other, “one bunk over, one seat behind, just across the table” (p. 6), a chasm widens between his memories of their childhood and her own. How would you describe that chasm? Think about the people you have grown up alongside: siblings, cousins, friends. What is your favorite story about them? How might they tell the same story? What stories might be missing from their knowledge of you? What questions might you ask them in order to uncover stories that you might not know?

- Across the collection, Taussig confronts systems that shape our histories and our culture—racism, sexism, ageism, classism, homophobia, size discrimination, housing discrimination. In doing so, she names the many ways in which those systems intersect, isolate, limit, and prescribe: the way they restrict things to something they “should” be rather than freeing people to imagine what “could” be. Can you think of some examples of this from the book? What about something in your own life, or in the life of someone you know, that is (or has been) limited to what “should” be rather than would “could” be? Who or what do you think framed that thinking?

- In the essay, “An Ordinary Unimaginable Love Story,” Taussig pens a tender meditation on love and the structures that attempt to define it. “Getting married meant an ostentatious wedding where I didn’t feel present or real—it was trying to fit into a role I’d seen play out countless times in stories that didn’t represent me…. Was there a way to build our own structure? To reimagine what two people can be to each other? To wipe the slate clean and create something from scratch?” (p. 48) Think about the people you love. What roles do you hold for each other? How do you honor each other’s distinct selves? What unique rituals, habits, rhythms, or practices of care have you co-created?

- In the same essay, Taussig traces her adolescent search for love: being disabled and longing for a love and a wedding like the kind depicted in the romantic comedies she grew up watching in the early 2000s. Think about the stories you grew up watching, hearing, absorbing. Did those stories have any kind of impact on what you imagined for your own life story? What kind of story do you wish you could have seen?

- In the essay “Feminist Pool Party,” Taussig unpacks the ways in which disability is often left out of feminist discourse, pushing back against the exclusivity of mainstream feminist spaces. How would you have described feminism before reading this essay? Did your idea of feminism change as you read? How does Taussig describe the relationships between gender and bodies? Between desire and selfhood?

- Taussig writes often about the importance of imagination and curiosity in expanding access, choice, and opportunity for those who have been historically marginalized. “This is the wild emancipation I wish for all of us…a world that instead strives to invite more, include more, imagine more” (p. 17). Can you think of ways to apply this in your community?

- In the essay, “More Than a Defect,” Taussig shares a glimpse of her first year teaching in a high school classroom. In that classroom—and for her readers—she introduces two lenses through which people perceive disability: the medical model and the social model. Were either of these models familiar to you? When you think about the places you visit in your day-to-day life—your office, your local grocery store, a nearby park—which model do you think shaped those places? What might this reveal about your world? About who has decision-making power within it?

- In the essays “More Than a Defect,” “The Real Citizens of Life,” and “The Price of Your Body,” Taussig draws our attention to the common categories of “disabled” and “not disabled,” and asks us to examine the limitations of those categories. What are some of those limitations? Why might those terms come up short? If we think about disability as a social process rather than a human category, how might we re-examine our own assumptions about disability?

- Taussig’s collection draws from years of writing and thoughts shared through her Instagram account, @sitting_pretty. Were there any moments in the book that felt particularly visual or scenic to you? How do you think your reading of these essays would have changed if you had experienced them through the medium of social media? Through images?

- In one of the last essays of the collection, “The Complications of Kindness,” Taussig writes about the many ways in which “being kind” and its close cousin, “being nice,” can flatten the experiences of disabled people into ableist narratives of victimhood or otherness. Did this essay disrupt your understanding of kindness? Have you experienced different types of kindness in your life (some welcome, some unwelcome)?

- In an introduction to an interview with Taussig for the National Endowment for the Arts Art Works podcast, Josephine Reed describes the tone of Sitting Pretty as “conversational...mak[ing] it feel as though you're talking with a very smart, funny, and thoughtful friend.” Do you agree? If not, why not? If so, in what ways did this conversational style of writing affect how you experienced—or related to—the essays?

- Across the book, Taussig tells a few of the same stories from different angles: the dissolution of her first marriage; a taxing search for accessible affordable housing as a single woman in Kansas City; the predictable tempo of her father's daily commute. Why might Taussig keep coming back to these stories in different ways? Can you think of any other moments in the book where this kind of telling and retelling occurs?

- At the end of the book, Taussig includes a short section titled “Postscript,” in which she shares a few brief updates from her life in the year after her book manuscript was submitted. Did the addition of a postscript enhance or change your experience of the book?