There, There

Overview

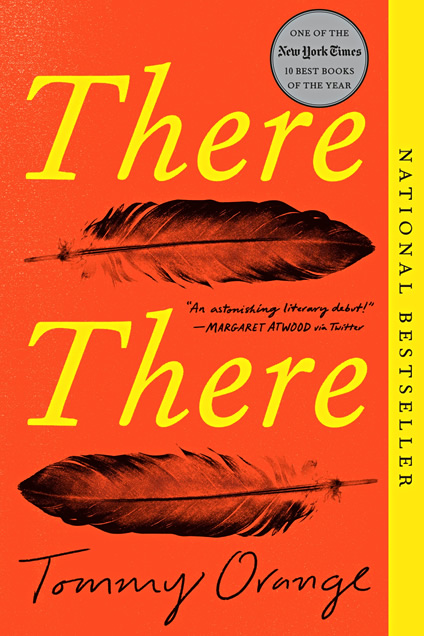

A finalist for the 2019 Pulitzer Prize and recipient of the 2019 PEN/Hemingway Award, Tommy Orange’s There There follows 12 characters from Native communities as they travel to the Big Oakland Powwow, all connected to one another in ways they may not yet realize. Together, this chorus of voices tells of the plight of the urban Native American, “sublimely render[ing] the truth of experiences that are passed over” (San Francisco Chronicle). “Brilliantly, furiously, magnificently, tragically, the story of America” (Elle), Orange crafts a novel of “pure, soaring beauty” (New York Times Book Review), “pulling together the intimacies of family, community, history, and violence” (Rumpus). “There There drops on us like a thunderclap; the big, booming, explosive sound of twenty-first-century literature finally announcing itself,” writes award-winning novelist Marlon James. “Essential.”

“We are the memories we don’t remember, which live in us, which we feel, which make us sing and dance and pray the way we do, feelings from memories that flare and bloom unexpectedly in our lives like blood through a blanket from a wound made by a bullet fired by a man shooting us in the back for our hair, for our heads, for a bounty, or just to get rid of us.” — There There

In There There, Tommy Orange traces the intersecting lives of 12 characters from Native communities whose voices and perspectives converge and conflict and reach across generations. Patterns of chance and circumstance draw each character towards the first Big Oakland Powwow: 14-year-old Orvil, coming to perform traditional dance for the first time; Jacquie Red Feather, newly sober and trying to make it back to the family she left behind; Dene Oxendene, pulling his life together after his uncle’s death and working at the powwow to honor his memory. Together, they tell of the plight of the urban Native American—grappling with a complex and painful history, with an inheritance of beauty and spirituality, with communion and sacrifice and heroism.

Throughout the novel, Oakland, California, is brought to life in kinetic detail. For the characters of There There, Oakland is the faded pink of the Tribune Tower, the sound of waves against rocks, the smell of a bus stop on Fourteenth and Broadway, the pull of a wound that never quite healed, the quality of light as the sun sets over San Francisco Bay. In Oakland, the past exerts itself on the present. Dene rides the BART and remembers the ancestral lands buried under “glass and concrete and wire and steel, unreturnable covered memory” (p. 39). Edwin Black joins the Big Oakland Powwow committee and confronts the “double-blind” (p. 77) of Indigenous art—modernity alongside tradition—exploring what it means to be of a place and of a people. As Jacquie prepares to return to Oakland, she revisits the memories and people that she left behind, people who have grown and changed without her. After his brother’s death, Daniel Gonzales watches Oakland from the camera of a drone, High Street to West Oakland, gentrification captured from a birds-eye view.

“We haven’t seen the Urban Indian story. What we’ve seen is full of the kinds of stereotypes that are the reason no one is interested in the Native story in general” (p. 40), Dene says as he presents his documentary project to a grant application panel. This tension—between the stories that free and the stories that trap—animates the entire novel. As he explores his uncle’s interview records, Dene struggles to distinguish between transcription and script. Jacquie and Harvey’s memories of Alcatraz confirm and contradict each other. The devastating events of the day of the Big Oakland Powwow are told across shifting perspectives, evading easy definition. By documenting contemporary urban Native life in all its complexities, Orange demonstrates that the rural nostalgia often invoked in stories about Native people is itself a kind of colonialism. “Buildings, freeways, cars—are they not of the earth?” Orange writes in the novel’s prologue. “Urban Indians feel at home walking in the shadow of a downtown building. We came to know the downtown Oakland skyline better than we did any sacred mountain range, the redwoods in the Oakland hills better than any other deep wild forest…Being Indian has never been about returning to the land. The land is everywhere or nowhere” (p. 11).

- The prologue to a novel often sets the stage for what’s to follow. In what ways did the prologue to There There set the stage for the fictional story? What are some of the themes that emerge? Which events described in the prologue were familiar or unfamiliar to you? From whose perspective have you encountered these events and stories?

- On page 7, Orange states: “We’ve been defined by everyone else and continue to be slandered despite easy-to-look-up-on-the-internet facts about the realities of our histories and current state as a people.” Why do you think this is? How do the characters in There There resist or grapple with the simplification and flattening of their cultural identity?

- In the same chapter, Orange writes: “Being Indian has never been about returning to the land. The land is everywhere or nowhere” (p. 11). What do you think he means by this?

- How is the city of Oakland characterized in the novel? How does the city’s gentrification affect the novel’s characters? Their attitudes toward home and stability?

- In the first chapter of the novel, Tony Loneman notes that part of his “street smarts” is an awareness of what people truly think about him: “They look at me like I already did some shit, so I might as well do the shit they’re looking at me like that for” (p. 17). Can you relate to Tony, or know someone who might? In what other ways do stereotypes and preconceptions we hold about other people affect our behavior? How might they affect the behavior of those we are stereotyping?

- When readers are first introduced to Dene Oxendene, we learn of his impulse to tag various spots around the city. Are there graffiti artists in your own neighborhoods or communities? How might graffiti change or recontextualize a space?

- When Two Shoes attempts to encourage Opal Viola Victoria Bear Shield to join the group of teenagers that hang out along the shoreline on Alcatraz, Opal tells him to “stop talking like an Indian…You’re not an Indian, TS. You’re a teddy bear” (p. 51). In response, Two Shoes tells her an anecdote about Teddy Roosevelt. Had you heard this anecdote before? How did it affect your experience of their conversation? Are there other moments in the novel where characters attempt to define the authenticity of Indian identity?

- On page 58, Opal’s mother tells her that she needs to honor her people “by living right, by telling our stories. [That] the world was made of stories, nothing else, and stories about stories.” What is the relationship between storytelling and power in the novel? Between storytelling and historical memory?

- How is femininity depicted in There There? What roles do the female characters assume in their community? Within their families?

- On page 77, Edwin Black asserts, “The problem with Indigenous art in general is that it’s stuck in the past.” How does the tension between modernity and tradition emerge throughout the narrative? Which characters seek to find a balance between honoring the past and looking toward the future? Are they successful?

- When Orvil asks his great-aunt why she never taught him and his brothers anything about being Indian, she responds: “Cheyenne way, we let you learn for yourself, then teach you when you’re ready” (p. 199). Despite Opal’s reluctance, Orvil chooses to participate in the powwow. How do his brothers react to it? What is the powwow’s importance for each of the Red Feather brothers? Did the Interlude on pages 134-141 affect your reading of the Big Oakland Powwow and its events?

- In There There, generational attitudes toward spirituality in the Native community are diverse and wide-ranging. Which characters embrace their elders’ spiritual practices? Which doubt their efficacy? Are there any moments in the book where spirituality offered a unique explanation about—or perspective on—an event?

- Tony’s perspective both opens and closes There There. Why do you think Orange made this choice for the novel?

- In interviews, Orange frequently refers to There There as a “polyphonic” novel. In literature, a polyphonic novel is one that gives weight to a variety of simultaneous points of view and voices: sometimes conflicting, sometimes in agreement. Why might Orange have chosen this structure for his novel? Have you read any other books that rely on this structure? What is gained by featuring multiple perspectives? What is lost?

Source material for There, There discussion questions from Penguin Random House.