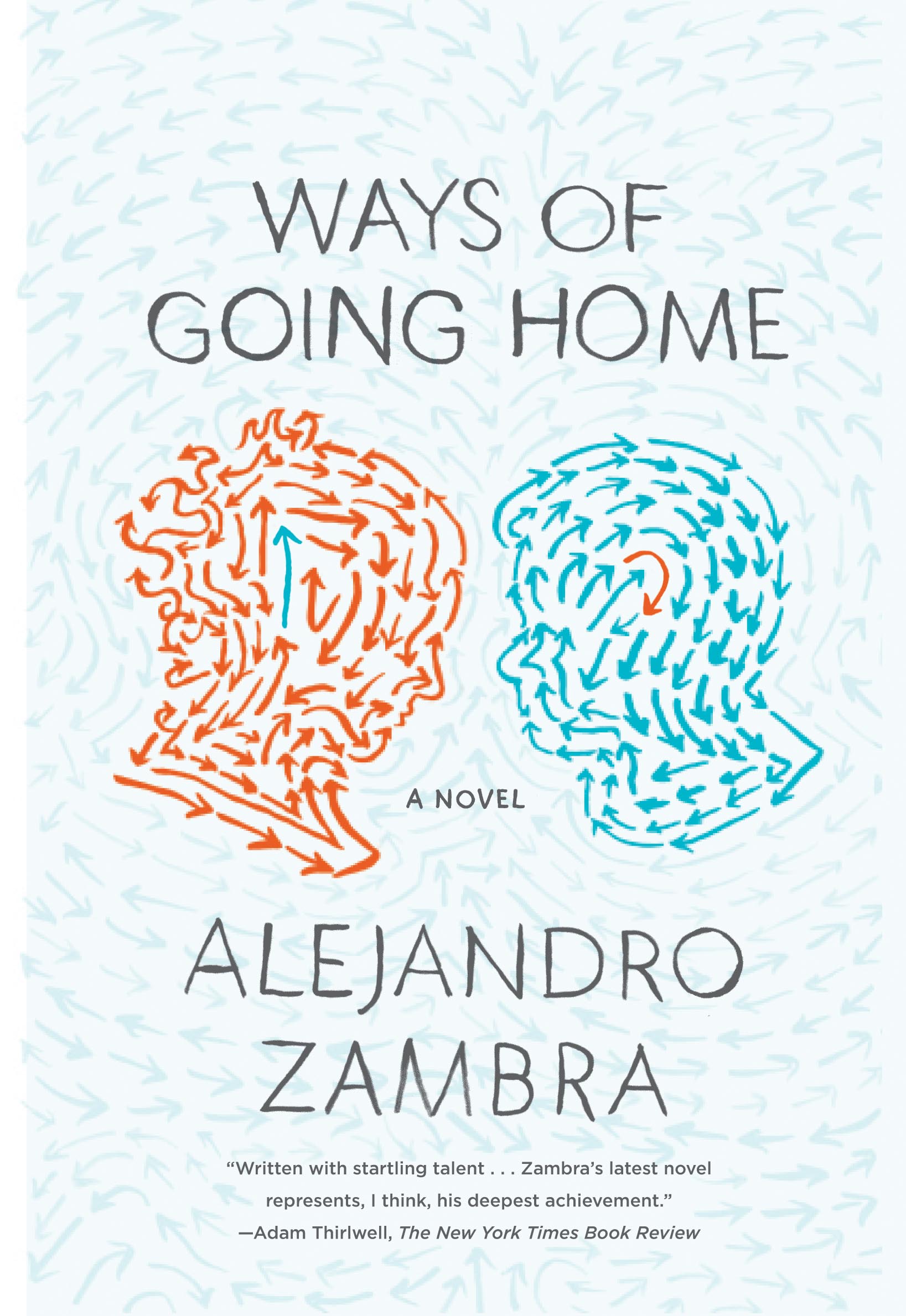

Ways of Going Home

Overview

Called "Latin America's new literary star" (The New Yorker), Alejandro Zambra is a popular writer in his native Chile. Born two years after the coup that brought down President Salvador Allende and installed Augusto Pinochet, Zambra writes from the perspective of a generation that was learning to read and write as their parents were becoming victims of, or accomplices to, brutal human rights violations. Ways of Going Home explores this theme by switching between the story of a young boy growing up in the Pinochet years and the story of the writer who is writing the boy's story. "It is structurally exquisite," writes The New Yorker. "In a political culture of actual disappearance, how can the writer not be acutely sensitive to questions of fictional ethics—to the whole complicated business of fictional lying, of inventing parallel worlds, of game-playing, of narrative presence and absence?" Writes Edwidge Danticat for Granta, "I envy Alejandro the obvious sophistication and exquisite beauty of the pages you are about to read, a work which is filled with the heartfelt vulnerability of testimony."

"While the country was falling to pieces, we were learning to talk, to walk, to fold napkins in the shape of boats." —from Ways of Going Home

Overview

Called "Latin America's new literary star" (The New Yorker), Alejandro Zambra is a popular writer in his native Chile. Born two years after the coup that brought down President Salvador Allende and installed Augusto Pinochet, Zambra writes from the perspective of a generation that was learning to read and write as their parents were becoming victims of, or accomplices to, brutal human rights violations. Ways of Going Home explores this theme by switching between the story of a young boy growing up in the Pinochet years and the story of the writer who is writing the boy's story. "It is structurally exquisite," writes The New Yorker. "In a political culture of actual disappearance, how can the writer not be acutely sensitive to questions of fictional ethics—to the whole complicated business of fictional lying, of inventing parallel worlds, of game-playing, of narrative presence and absence?" Writes Edwidge Danticat for Granta, "I envy Alejandro the obvious sophistication and exquisite beauty of the pages you are about to read, a work which is filled with the heartfelt vulnerability of testimony."

Introduction to the Book

"In fiction you are closer to the truth, because everything you say is, from the start, arguable." — Alejandro Zambra in McSweeney's

How do you understand who you are if you can't trust your memories? How do you find meaning in your life when you feel like a secondary character in the lives of others? Alejandro Zambra's slim novel, Ways of Going Home, asks big questions about a generation that grew up under the brutal dictatorship of Chile's Augusto Pinochet. It was a generation of children who, shielded by their parents, played games and learned to walk and talk and live happily without knowing the reality of what was happening around them.

Zambra's 2013 novel tells two separate but connected stories in four alternating chapters. The first story unfolds with a fictional account of a nine-year-old boy who we later meet as a 20-year-old in chapter three. In the other chapters we meet the novelist who's writing the fictional story in the first and third chapters and is struggling with where to go with it. The parallel narratives raise questions about the manner in which we reap and revise memories to try and construct and communicate the stories that define who we are. "This small novel contains a surprising vastness, created by its structure of alternating chapters of fiction and reality," writes The New York Times. "Almost every miniature event or conversation is subject to a process of revision, until you realize that Zambra is staging not just a single story of life under political repression, but the conditions for telling any story at all."

The novel opens in the aftermath of an earthquake. A boy develops a crush on Claudia, an older girl who asks him to spy on a suspicious man named Raul who lives alone and who instills fear in the boy's guarded parents. Years later, he tries to write a novel but comes up short on material from his own, uneventful childhood. Instead, he tracks down Claudia to learn the real reason for her interest in Raul and about her traumatic history. In the second chapter, we're introduced to the restless novelist who is writing the story in chapter one about the boy and Claudia and Raul. The novelist is trying to get back together with his ex-girlfriend, Eme. He feels stifled by nostalgia and the frustration of writer's block.

As Zambra ruminates on larger issues, he also hones in on singular moments that may seem innocuous but that tap into deep and common emotions. The boy at the beginning of the novel, for example, gets lost and separated from his parents. He's scared, but finds his way home before they do. His parents keep searching for him and are scared, too. The boy, safe at home, imagines that they are the ones who are lost. Once they are all home, his mother, full of love and still fraught with fear, asks why he went a different way; the boy doesn't answer.

Later in the novel, the character, older now, reflects on an intense conversation with classmates in which they shared stories about their families, stories about the dead and whom they left behind. He feels strangely bitter for not being able to share a similar story. Instead, he thinks about sharing Claudia's story, but has an epiphany: her story is not his story. Finding and sharing our own stories, he implies, is one way of "going home."

NOTE: To differentiate the key male voices associated with Ways of Going Home, we use “the author” to refer to Zambra; “the narrator” to refer to the character who's writing the novel and speaks to us in the second and fourth chapters; and “the young man” to refer to the boy-turned-young-adult in chapters one and three who is the subject of the narrator's novel.

- The first chapter of Ways of Going Home is called “Secondary Characters.” What does it mean to be a secondary character? Who are the secondary characters of this book? How do they each cope with this role?

- Why do you think the author decided to structure his book the way he did? How would your reading experience be different if the author began with the narrator's story instead of the young man's?

- “While the adults killed or were killed, we drew pictures in a corner,” writes the narrator (p. 41). How are children insulated from the adult world in Ways of Going Home? Do you believe adults should try to shield children from a harsh reality? If so, to what degree? How do the author's characters try to come to terms with their innocence and guilt?

- The novel takes place during a time of political turmoil in Chile's history. What do you know about Salvador Allende? About Augusto Pinochet? What might you imagine life was like for children of both rich and poor families under the governments of each? Where does the author draw the line between the political and the personal? In what ways does the time in which we live shape who we are?

- Why do you think the author keeps both the narrator and the young man nameless? Why does the narrator feel it's “a relief” (p. 37) not to give the characters in his novel last names? What effect did this have for you as a reader? Are there other places in the book where names of people, places or things might signify larger issues at play?

- The novel's plot is built around people who have “known” each other for many years—parents, spouses, childhood friends. What does Eme mean when she tells the narrator that, for a relationship to work, “sometimes you have to pretend we've just met” (p. 119)? Do you ever wish you could meet someone again for the first time?

- How does the narrator's relationship with Eme compare to the young man's relationship with Claudia? How does one inform the other? Do you agree with Eme that it was a kind of “robbery” (p. 133) when the narrator gave parts of her life story to Claudia?

- Referring to the 1985 earthquake in Chile at the beginning of the novel, the young man says, “I think it's a good thing to lose confidence in the solidity of the ground” (p. 9). What do you think he means by this? Do you agree? Why do you think the author chose to begin and end the book with earthquakes?

- What takeaways do you draw from the book about who “owns” stories and what it means to try to tell them? What happens (or should happen) when people cannot or will not tell their stories? The young man tells us that, when we tell others' stories, “we always end up telling our own” (p. 85). Do you agree?

- “My story isn't terrible...there were others who suffered more, who suffer more,” says Claudia (p. 97). Why does she compare her suffering to others? Have you ever found it difficult to empathize with someone else because your own pain felt more immediate? Or vice versa?

- The book includes two similar scenes involving a late-night conversation: in the first scene the narrator speaks with his mother (p. 62-65); in the second scene the young man speaks with his mother (p. 107-111). How do they diverge? Why do you think the author chose to “repeat” this particular scene? Did you read the first scene differently after reading the second one? Were there other scenes that were similar for both the narrator and the young man?

- Says the narrator: “To read is to cover one's face. And to write is to show it” (p. 50). What do you think he means by this? What did you learn from the novel about the struggles writers face?

- Ways of Going Home is a book in translation (from Spanish into English). What might you imagine are the difficulties in bringing a story from one language into another?

- What do you make of the title?

- In what ways does the narrator change when, as an adult, he discovers more about his parents' past? How does this affect their relationship? Did you ever discover something new about your parents that made you view them differently? If you have children, how do you think they will remember you?

Engaging Young Audiences with Circus and Dance Performances in Bronx, New York

The Bronx Council on the Arts is making strides to incorporate new youth-focused programs after their successes with events and activities that engaged younger audiences during their NEA Big Read programming of Ways of Going Home. Programming they called the biggest successes were a dance performance and a series of circus rehearsals/performances based on themes from the book by the youth circus troupe Cirque Du Vie.

|

“Cirque Du Vie, who are served by The Point in Hunts Point, a low-income district in the South Bronx..., based an entire performance on the book, learning about abstraction and experimenting with non-literal forms of expression,” just as the book unfolds in a nontraditional, nonlinear way. The performers were taught how to characterize abstract themes drawn from the book—such as paranoia, espionage, trusting our memories, and telling our own stories—through pantomime, tightrope walking, and gesture.

After rehearsals, the performers also engaged in book discussions focused on the themes they animated in their abstract performances. “The young people we engaged with discussed their evolution as performers and shared some of their own creative writing pieces, mostly poetry, as part of the book discussions preceding rehearsals…. They were hosted by local writers and youth mentors Sydney Valerio, Natalie Caro and Charlie Vazquez…. Similar engagement occurred at the dance performance and book discussion featuring choreographer Jasmine Hearn and author Peggy Robles Alvarado, where LGBTQ youth were the focus of our engagement efforts, all made possible by NEA Big Read support.”

— From a final report by Bronx Council on the Arts, an NEA Big Read grantee in FY 2017-18.

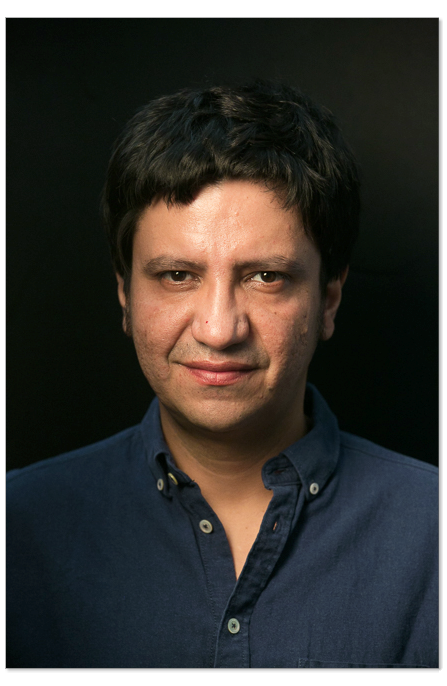

Photo courtesy of Megan McDowell

Photo courtesy of Megan McDowell