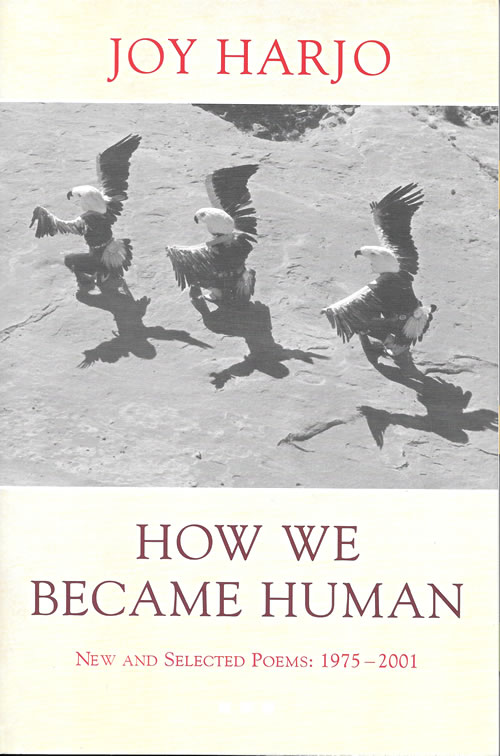

How We Became Human

Overview

This title will no longer be available for programming after the 2020-21 grant year.

Writer and musician Joy Harjo was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma and is a member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. Her many awards include a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Native Writers Circle of the Americas; the William Carlos Williams Award from the Poetry Society of America; the Wallace Stevens Award from the Academy of American Poets; the American Indian Distinguished Achievement in the Arts Award; and two National Endowment for the Arts creative writing fellowships. How We Became Human (W.W. Norton, 2002) offers an introduction to her poetry over the first 26 years of her career, including poems from her groundbreaking book She Had Some Horses (Thunder's Mouth Press, 1983). "To read the poetry of Joy Harjo is to hear the voice of the earth, to see the landscape of time and timelessness, and, most important, to get a glimpse of people who struggle to understand, to know themselves, and to survive" (Poetry Foundation). Says author Sandra Cisneros, "Her hero's journey is a gift for all those struggling to make their way." "Joy Harjo is a giant-hearted, gorgeous, and glorious gift to the world," says author Pam Houston. "Her belief in art, in spirit, is so powerful, it can't help but spill over to us—lucky readers."

"We were never perfect. Yet, the journey we make together is perfect on this earth who was once a star and made the same mistakes as humans." —from How We Became Human

Introduction

"Don't worry about what a poem means. Do you ask what a song means before you listen? Just listen." — Joy Harjo

To open Joy Harjo's How We Became Human: New and Selected Poems 1975-2001 (W.W. Norton, 2002) is to be immersed in the power of nature, spirituality, memory, violence, and the splintered history of America's indigenous peoples. To read her poetry is to get drawn into the rhythms, sounds, and stories of Harjo's Creek heritage. The collection offers a glimpse into the first quarter-century of Harjo's career, and includes an introduction about the circumstances at play in her life when she wrote the poems. Drawing together "the brutalities of contemporary reservation life with the beauty and sensibility of Native American culture and mythology," writes Publishers Weekly, the book shows "the remarkable progression of a writer determined to reconnect with her past and make sense of her present." "I am driven to explore the depths of creation and the depths of meaning," said Harjo. "Being native, female, a global citizen in these times is the root, even the palette" (Terrain).

The collection begins with poems from Harjo's first two chapbooks, The Last Song (Puerto del Sol Press, 1975) and What Moon Drove Me to This (I. Reed Books, 1979). Many of the poems explore the idea of place—a longing to get from one place to another, a longing for a place to feel safe and whole. In the poem "3 A.M," the speaker has an epiphany as she travels home from Albuquerque in the middle of the night. In "Are You Still There?" the speaker has a fraught conversation across miles of telephone wire. In "Crossing the Border," the speaker feels a crushing sense of suspicion as she crosses into Canada. In contrast, poems such as "Watching Crow, Looking South Toward the Manzano Mountains," and "for a Hopi silversmith" convey a sense of peace and connection that comes from observing natural beauty.

The collection also includes poems from She Had Some Horses (Thunder's Mouth Press, 1983), now considered to be a classic. The title poem, propelled forward by the chanting of the title phrase, wrestles with the question of how our own contradictory parts can coexist. The question carries over into other poems, such as "Call It Fear," and "The Woman Hanging from the Thirteenth Floor Window." "I feel strongly that I have a responsibility to all the sources that I am," said Harjo, "...to all voices, all women, all of my tribe, all people, all earth" (Poetry Foundation). Several of the poems are infused with spiritual and historical memory, such as "New Orleans," which describes how an American city was built over a place where indigenous people used to live, and how their memory survives in the stones.

For her book Secrets from the Center of the World (University of Arizona Press, 1989), Harjo collaborated with astronomer and photographer Stephen Strom, writing prose poems inspired by his photographs of Navajo country. In these short, direct, often philosophical poems—such as "My House Is the Red Earth" and "Anything That Matters"—Harjo describes the center of the world as a modest place, one easily overlooked, but essential. In Harjo's book, In Mad Love and War (Wesleyan University Press, 1990), the poems, while also often concerned with the notion of place, confront "violence, revenge, loss, disillusionment, [and] brutality" in order "to reach a human, miraculously graced center" (Choice). "...How do we imagine ourselves with an integrity and freshness outside of the sludge and despair of destruction [resulting from colonization]?" asks Harjo (PEN America).

In her introduction to How We Became Human, Harjo writes that she doesn't believe there's a distinction between poetry, stories, events, and music—a point of view that seems to have especially informed the poems from The Woman Who Fell from the Sky (W.W. Norton, 1994), and A Map to the Next World: Poems and Tales (W.W. Norton, 2000), which blend myth and traditions of music and oral storytelling with everyday experiences and historical realities. "If Whitman were a Muskogee jazzman, he would have written [The Woman Who Fell from the Sky]," writes Booklist. Of A Map to the Next World, Publishers Weekly writes: "[The book] reveals regenerative human cycles that occur even in the midst of the most oppressive histories." In that book's title poem, Harjo splices together unexpected imagery and sensations—for example, the smell of traditional cooking and the view of a far-away galaxy—to explore what it truly means to be "human."

In addition to the selections from past collections, How We Became Human includes notes about many of her poems, as well as a number of previously unpublished poems, including "When the World as We Knew It Ended," written after September 11, 2001, and "Morning Prayers," which references the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. speech "I've Been to the Mountaintop." Among these newer poems is also "It's Raining in Honolulu," from which the collection's title—"how we became human"—is drawn.

"Alive with compassion, pain and love, this book is unquestionably an act of kindness," writes Publishers Weekly. "[Harjo] contends that poetry is not only a way to save the sanity of those who have been oppressed to the point of madness, but that it is a tool to rebuild communities and, ultimately, change the world."

- Some of the poems in How We Became Human are named after places, e.g., Anchorage, New Orleans, Santa Fe, and Honolulu. Many also refer to other places within the poems themselves (e.g., Nigeria and Cambodia). How are places connected to memories of events, emotions, or people? How does your own familiarity, or lack of familiarity, with the places Harjo names affect how you think about the poems?

- Journeys are common in Harjo's poems: going places, leaving places, or experiencing places in between. The poem “3 A.M.,” for instance, begins “in the Albuquerque airport / trying to find a flight”. The poem “Crossing the Border” describes a tense passage from Michigan into Canada. In what ways might the journeys mean more than the places themselves? How has a journey in your life changed the way you think about a familiar place?

- In the poem “Bird,” Harjo refers to the life and music of bebop saxophonist Charlie Parker. Harjo, who also plays the saxophone in her own band, writes that “All poets / understand the final uselessness of words”. What is the relationship between music and poetry? What do you think Harjo feels music can do that a poem cannot?

- Many of Harjo's poems are about the relationship between humans and nature. In “Remember,” for instance, Harjo urges the reader to “remember the earth whose skin you are: / red earth, black earth, yellow earth, white earth / brown earth, we are earth”. What is it about the natural world that Harjo asks us to realize or remember?

- Poems like “For Alva Benson, And For Those Who Have Learned to Speak” differentiate the native languages of American Indians from the languages of the Europeans who colonized the Americas. How is language tied to cultural identity? How can language be a tool for oppression or survival? How does Harjo approach the colonial legacy of the English language in her poetry?

- Certain animals show up frequently in Harjo's poems, including horses, blackbirds, crows, deer, and snakes. Did the way she describes these animals and their personalities surprise you? Do the same animals mean the same things each time they appear in her poetry?

- In poems such as “The Woman Hanging from the Thirteenth Floor Window”, “She Had Some Horses”, “For Anna Mae Pictou Aquash”, and “The Flood”, Harjo writes about the experiences of women, including the often conflicting demands that society makes on them. How do women navigate gender roles in Harjo's poems? In what ways do you feel the pressure of gender roles in your own life?

- In “A Postcolonial Tale,” Harjo writes that “it was as if we were stolen, put into a bag carried on the back of a white man who pretends to own the earth and the sky”. How does she emphasize the history of native peoples in her poems? Has reading How We Became Human affected your understanding of American history?

- Beginnings, endings, and “the next world” all play a large role in Harjo's work. How does she challenge assumptions about time? What is more influential in shaping the world, continuity or change?

- “Returning from the Enemy” begins with the lines “It's time to begin. I know it and have dreaded the knot of memory / as it unwinds in my gut”. Just a few lines later, the poem continues: “The wake of history is a dragline behind me.” Where do memory and history overlap, and where do they diverge? Do the two serve different purposes?

- One way to talk about a poem is to describe its form. How We Became Human includes poems in a range of forms, distinguished by elements such as line length (short lines, long lines, prose), line breaks (where a line starts and ends), stanza shape, capitalization, and punctuation, to name just a few. Are there places where one or more of these choices affected how you read a particular poem? How have Harjo's forms changed over time?

- “Song for the Deer and Myself to Return On” is dedicated to one of Harjo's former students, and in her note to the poem she explains: “My workshop was the first time he realized that he could abandon the strict metrics and patterns of European forms and take up more organic forms, forms that fit his Muscogean subject matter”. When you think about poetry, what kind of poem first comes to mind? Do Harjo's poems match your expectations for what a poem should look and sound like?

- In “A Map to the Next World,” Harjo writes, “We were never perfect. // Yet, the journey we make together is perfect”. What is her outlook on the future? What does she envision for humankind? Who is the “we” in this poem?

- In the book's final poem, “Rushing the Pali,” Harjo describes the “mythic roots” that are present everywhere, even in daily life. What place do myths have in your own life? Do you want myths to teach you something, or to entertain you? Whom do myths belong to? Are they universal, or do their meanings depend on the cultures that created them?

- How We Became Human takes its title from a line in one of the book's last poems, “It's raining in Honolulu”. How is the phrase used in that poem? What does it signify as the title of the book? Are there any other individual lines that stood out to you independent of the poems they come from, or any that you think sum up what the book is about?

- How We Became Human includes more than 30 pages of notes that explain and give context to the poems. If you read the notes, did they help you understand the poems? Should poets and other artists explain their work? Can a poem mean something different from what its author says it means?

- After reading this book, is it possible to generalize about what makes a “Joy Harjo poem”? Do you think you could recognize other poems by Harjo, based on the poems in How We Became Human?