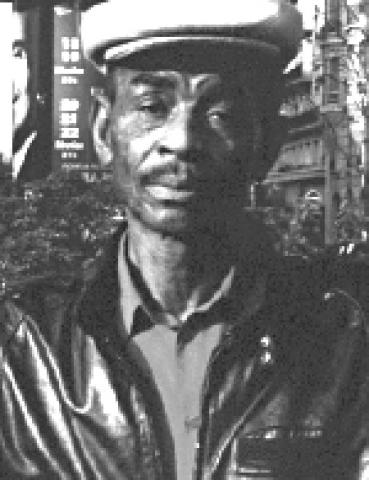

National Endowment for the Arts Statement on the Death of National Heritage Fellow John Dee Holeman

It is with great sadness that the National Endowment for the Arts acknowledges the death of African American dancer, musician, and singer John Dee Holeman, from Durham, North Carolina, recipient of a 1988 NEA National Heritage Fellowship, the nation’s highest honor in the folk and traditional arts.

Photo courtesy of the NEA

John Dee Holeman was born April 24, 1929, in Orange County, North Carolina, and was raised on a small family farm. He first heard blues at house dances and country gatherings in the African American community. He began picking guitar when he was 14 years of age, quickly learning the Piedmont tunes he heard his uncle and cousin play.

North Carolina Piedmont Blues musician Fulton Allen (AKA Blind Boy Fuller) was immensely popular at that time, and Holeman was influenced by his recordings of the distinctive Piedmont sound. The Piedmont region encompasses a chain of foothills that runs between the Appalachian Mountains and the Atlantic coastal plain, from Virginia through North and South Carolina and Georgia down to Florida. String-band music thrived in the region — performed by both Blacks and whites — and the blues arose in the area, probably reflecting an earlier musical tradition than the Mississippi Delta blues, shaped by the sound of the banjo and by still-remembered African plucked instrumental techniques.

As a young man, Holeman also listened to traveling bluesmen from other areas of the South, to recordings from Chicago and the Delta, and to Black and white musicians on the radio. While still a teenager, he started playing music at house parties, Saturday night suppers, and community gatherings throughout his area of rural North Carolina. At country dances, Holeman also learned the tradition of "patting juba." Juba, the use of complex hand rhythms to provide timing for dancers, is a centuries-old tradition among Africans and African Americans. Where Holeman grew up, it was customary when party musicians took a break for males to engage in competitive solo dancing accompanied only by hand or "patting" rhythms. "Juba" refers to both the complex hand rhythms and the dance traditionally done to them. The dance done to the juba rhythm is also called "buckdance," "bust down," and "jigging." "Patting" is distinguished from clapping by virtue of the varied pitches the patting hand elicits from the arms, chest, thighs, and flanks.

As Holeman's dancing skills developed, he teamed up with Fris Holloway, an experienced "patter" and blues piano player. Together, and independent of each other, the two were able to produce rhythmic complexities—Holeman on the floor and Holloway on his own body. The pair performed at house parties before taking their work on the road throughout the South, and their distinctive style of music and dance is memorably documented in the 1989 film Blues Houseparty. Years later, they were invited by the U.S. State Department to participate as part of an ensemble performing in Southeast Asia.

For most of his life, Holeman had a day job to support himself and his family. In Durham, he was a heavy equipment operator and construction worker. Over the years, he was able to supplement his income by playing blues and "patting juba," though he never chose to pursue music as a full-time profession. In addition to the touring he did for the State Department, he played at festivals around the country and in concerts in Europe and Africa, where he also conducted workshops for students and other performers. In recent years, Holeman worked closely with Junious Brickhouse, bridging the gap between the old-style buck dancing and today’s urban street-dancing. As Junious Brickhouse says in this NEA podcast, “It’s helped me to see and understand and play and meet the elders of the arts forms that come before urban dance culture and understand the root of it all, which is the music, and understand a little bit better how do we connect to it and how do we work to preserve it.”

Contact

NEA Public Affairs, publicaffairs@arts.gov