SPPA Notable Quotable: Andrew Recinos, President & CEO, Tessitura

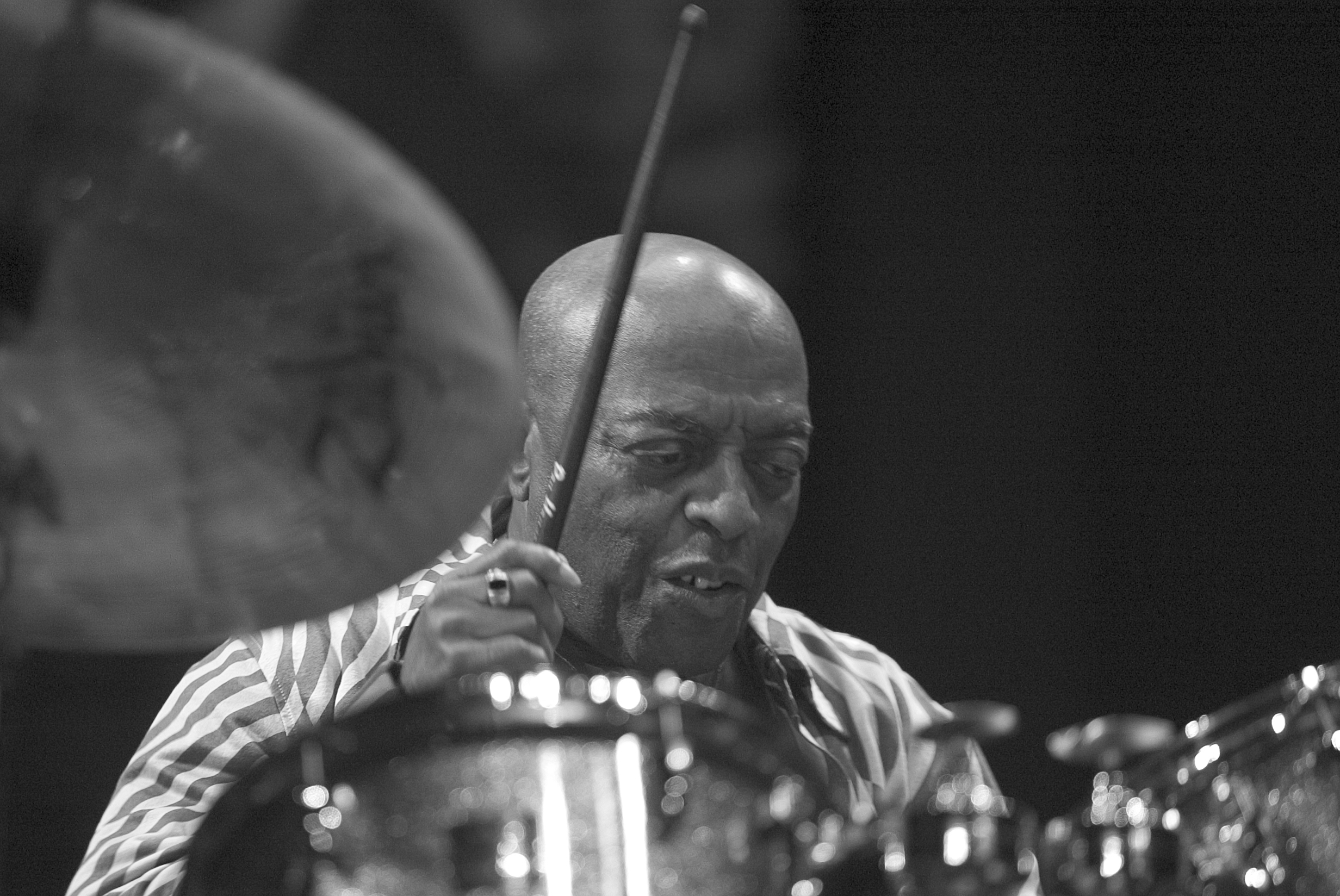

Photo by Joseph Mark

Photo by Joseph Mark

Dance Maker Academy Spring Performance students perform on stage. Photo courtesy of Art Maker

MUSIC CREDITS:

“NY” composed and performed by Kosta T, from the cd Soul Sand. Used courtesy of the Free Music Archive.

"Green Chimneys" from the album The Thelonious Monk Songbook performed by the Roy Haynes Trio. Produced by U-5, 2013.

"If I Should Lose You" from the album, Out of the Afternoon, performed by The Roy Haynes Quartet. Produced by Impulse! Records, 1996.

Excerpt from the Blues Walk composed by Lou Donaldson from his album Blues Walk, used courtesy of Blue Note Records, a division of EMI Capitol.

Excerpt of Alligator Bogaloo composed by Lou Donaldson from his album Alligator Bogaloo, used courtesy of Blue Note Records, a division of EMI Capitol.

Excerpt of Quicksilver composed by Horace Silver and performed by the Art Blakey Quintet, from the album, A Night at Birdland, used courtesy of used courtesy of Blue Note Records, a division of EMI Capitol.

Jo Reed: From the National Endowment for the Arts, this is Art Works, I’m Josephine Reed. Last week we lost two giants of music, drummer and 1995 NEA Jazz Master Roy Haynes who died at the age of 99 and 2013 NEA Jazz Master saxophonist Lou Donaldson. We’re saddened by their losses but are fortunate enough to have interviews with them both which we’re excerpting here in tribute to their extraordinary musicianship. Let’s start with Roy Haynes….and Green Chimneys composed by Thelonious Monk and performed by the Roy Haynes Trio.

(music up)

Roy Haynes defined the word style in every sense: from his distinctive drumming to his snappy clothes--he is first among equals. Known for his unique crisp drumming, Haynes may have been the most recorded drummer in jazz. In a career lasting more than 70 years, he played in a wide range of styles ranging from swing and bebop to jazz fusion and avant-garde jazz. He had been equally successful as a leader and as a sideman-- Thelonious Monk once described Haynes' drumming as "an eight ball right in the side pocket." Haynes collaborated with the who's who in the jazz world. As well as Monk, there’s Charlie Parker, Lester Young, Miles Davis, Danilo Perez, and Christian McBride to name only a very few.

Haynes had a reputation as a tough interview, he had a surprising amount of patience when he sat down with me at Jazz at Lincoln Center in 2014. Here's an excerpt of our talk.

Jo Reed:You got your start with Luis Russell.

Roy Haynes: Uh-huh.

Jo Reed:How did that happen?

Roy Haynes: It happened by what I was doing, and the way I was doing what I was doing. People talked about that, because Luis Russell didn't know anything about Roy Haynes until people told him. And then I was living in Boston at the time, I got a special delivery letter from New York from Luis Russell. He had never heard me, but he heard about me. And I guess it's probably the people that told him about me for him to stretch out and try to reach me, which is the way it happened.

Jo Reed:One of the first gigs you played with him was at the Savoy.

Roy Haynes: The first gig was at the Savoy.

Jo Reed:It was the very first. What was that like?

Roy Haynes: What was that like? It was…

Jo Reed: What was the Savoy like then?

Roy Haynes: The Savoy, you can't hardly describe it in anything that you'll know about, you've got to have a great imagination because a lot of people would come to the Savoy Ballroom, and they probably wouldn't even dance, there's so much excitement going on. First of all, they had two bandstands. They usually have a big band on one bandstand, and a small band, a combo, on the next bandstand. Back in probably the late '30s, early '40s they would have the battle of the bands. So there were two bands, they'd be battling. I used to hear a lot about it when I was young, in Boston. Because I think certain nights they would broadcast anyhow, from the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem to different stations, so I had heard about it then. When I first played there with Luis Russell's band I don't think the bands were really battling then, because it'd be a big band on one side; twelve, thirteen, fourteen-piece and a small combo on the other side, the other part of the bandstand, which was like twin bandstands together. But that was really an exciting period, because not only the people came to dance, some people would just stand in front of the bandstand and listen. They call that the "home of the happy feet" because people will-- a lot of people could dance like they were professional in those days, '40s, was when I first come to New York with the band. My first job, like I was saying, was at the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem. So it was a very exciting period.

Jo Reed:And as you said, Luis Russell of course had a big band.

Roy Haynes: Yeah, we had, I don't know twelve or thirteen-piece orchestra; three brass, maybe three trumpets, three trombones, three saxophones, three or four saxophones, and a guitar, and bass, and drums, and a great vocalist.

Jo Reed:Who was the vocalist?

Roy Haynes: Lee Richardson when I was with the band. He made hit records. One of his big records was "The Very Thought of You." He has this voice, "The very thought of you, and I forget to do…," and all the young girls would be screaming. We'd play theaters like the Earle Theater in Philadelphia, and we'd do five shows a day during that period.

Jo Reed: Five shows a day.

Roy Haynes: Oh, yes. And if they had a lot of people waiting in lines after each show, they would have to add another show to it. So you got a chance to make extra money, then. The more shows you did, the more money you made. And a lot of that wasn't always planned in advance. Sometimes it would just happen when it would happen, the last minute. People would be lined up to come in the theater waiting for people to leave so they could come in and catch the show.

Jo Reed:How important do you think that experience was for you as a performer, especially backing a-- playing in a big band?

Roy Haynes: Well, it was my first big band experience for one thing, which is something I wanted to do anyhow because I used to listen to a lot of the big bands like the Basie band when he had Papa Jo Jones playing drums. And also when he left they had other younger drummers that I would go and catch with the band. In fact, I did get a chance to play with that band a couple of times when I was much younger, also. But I was never a steady drummer with the band. I just filled in for a few nights.

Jo Reed: And Papa Jo Jones is one of the drummers that you listened to.

Roy Haynes: Oh, definitely. He was the main one. In fact, a lot of drummers my age during that time, in fact drummers of any age, usually were checking out Papa Jo Jones.

Jo Reed:What was it about his sound?

Roy Haynes: Not only his sound, his feeling, and the way he would do different things. It's hard to explain, because I'm talking about early '40s. I'm just beginning to be a professional drummer, and I'm listening to certain things that other drummers didn't do, and the way he would do what he did. The feeling came from here, it wasn't nobody to just practice. This was a natural drummer, which is what they told me I was. I was just born a natural drummer, so I could sort of relate to Papa Jo.

Jo Reed:You saw the birth of bebop. Did it grab you right away when you first heard it? Was it like an explosion in your mind when you first heard it?

Roy Haynes: Well, I don't know if I would look at it as an explosion, but it was something new that was happening. The tunes, like the compositions, and the way the different artists were playing, certain artists, the things that they were doing musically, yeah, it was something new, so it did grab me, yeah. I jumped right on it, yeah.

Jo Reed: And you played with Charlie Parker.

Roy Haynes: Yes, Charlie Parker hired me, I forget what year it was, 1949 I'm thinking, yeah. And I was with Lester Young during that period. And I know once there was a gig, a concert, in I think Baltimore, Maryland where there were two bands; Charlie Parker's band-- I was with Lester Young then. And Charlie Parker was there with his band, and his drummer at that time was Max Roach. So Max Roach's drums were set up on the stand, on the bandstand. And I said, "I'm going to sit my drums right beside his." Max was very popular then. And I was a young guy-- younger guy, a couple of years younger than him, just beginning to get popular also. So I said, "Yes, I'm going to set my drums right up next to his," and I did, and not even realizing that I would end up playing with Charlie Parker. I was with Lester Young then. And that was a great time of my life with the music, and a great experience to be playing with Lester Young opposite Charlie Parker.

Jo Reed:I would think it would be.

Roy Haynes: Oh, yes. That was a very exciting period.

Jo Reed: I seem to remember people saying Lester Young spoke in a very particular language. He was very funny, but you kind of had to understand where he was coming from to get what he was saying, did you find that to be the case?

Roy Haynes: Yeah, that was very true. Lester Young, he was one of the most, how can I describe him so people will understand, original people that I have ever met, not only in the way he dressed, the way he talked. He would talk-- if he just met you, he would talk his language to you. So some of the things you probably wouldn't understand what he was saying. But that's the way he was. He was a very original person all the way; the way he played, the way he dressed, and the way he talked. And it was not just a put-on thing, that's the way this man was.

Jo Reed: Were you sorry to leave that band and go with Charlie Parker in some ways?

Roy Haynes: I was happy because I wasn't just moving on to move on, I was going to be playing with Charlie Parker, one of the great persons. I went from Charlie Parker to Sarah Vaughan. it was great playing with Charlie Parker. He was a great genius. Sarah Vaughan was a genius also. They did a recording together that also inspired me. Charlie Parker was on a recording with Sarah Vaughan. Sarah Vaughan, I mean, she could just-- she knew the music, too. She knew the chords, the changes that she wanted the musicians, especially the keyboard player, to play for her. We have a lot of people that are great singers, but they don't always know the music or about what they're doing, they just do it naturally only, and they're gifted to do it that way. But Sarah Vaughan, she could pick up the music and read the music as well, a new composition that she never heard before. One of the differences of just playing with somebody who can sing, and not a great musician, but Sarah Vaughan was a great musician as well.

Jo Reed: You were with Thelonious Monk at the Five Spot with a great live recording. I think it was '50--

Roy Haynes: Late '50s or '60s, Yeah.

Jo Reed: What was it like playing with Monk?

Roy Haynes: It was great. I enjoyed it. I enjoyed every moment. Little Monk wasn't just an ordinary artist. He had a lot of feeling, a lot of imagination, and it was great. It was great playing with him. Only thing that was kind of strange, sometimes you had to wait hours before he would show up, so we wouldn't play until he arrived. So sometimes the club would be crowded with people waiting for Monk to come. But that was a long time ago. That was in the late '50s. That was yesterday.

Jo Reed: That was yesterday. Jazz has a reputation, rightly or wrongly, of being not a young person's music anymore. I'm often in audiences, and I always look around to try to see how old people are in the audiences, and they tend to be older audiences. And opening jazz up to younger people seems to me to be something that is a very significant thing to do, and that is something that you do. Your audiences, the demographics tend to be more skewed. I'm not saying they're all young by any means, but they do tend to be more skewed.

Roy Haynes: You're absolutely right. That's something, huh.

Jo Reed:I think so.

Roy Haynes: It's something for me to think about, too. Yeah. I think about it. Yeah, I really-- because sometimes I don't notice it right away. I know I've heard people say years ago, I'm not talking about the last two years, but even before that, "You draw a really young audience." Fifty years ago would say that about me, when I was much younger than I am. So I guess that has to do with the music, or the feel of the recordings, or something they heard or read about my music or something. I don't know. I'm one of the ones that-- I don't analyze things. I don't try to. Some of the-- a lot of the things that happen I just keep on keeping on, and don't try to figure them out. That's what I do on the bandstand, too, a lot of times. If I try to really figure out the music, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, I try to do it by what I feel rather than talk about it. Even if I have somebody new in my band, I don't sit down and tell them what I expect them to do, what I would like them to do. Usually they probably feel something, or heard from some way-- we don't talk about it much. And it works. It has been working. So I'm going to leave it alone…

Jo Reed: That was an excerpt of a 2014 interview with 1995 NEA Jazz Master Roy Haynes who died last week at the age of 99 one of the best drummers who ever played. We’re taking a quick break, we’ll return with our tribute to the late Jazz Master Lou Donaldson

(Music Up)

Jo Reed: And now our remembrance of 2013 NEA Jazz Master Lou Donaldson who passed away last week at the age of 98

Lou Donaldson's alto sax had been a force in jazz for more than six decades. He spent his early years in the bebop era, influenced heavily by Charlie Parker but Donaldson combined bop with a more soulful sound that was absolutely his own, it was a style of playing that earned him the nickname, Sweet Poppa Lou.

Donaldson made a series of classic records for Blue Note in the 50s, and Donaldson's first records with organist Jimmy Smith led to the groove-filled jazz of the 1960s and 70s. And Lou was an outstanding stage presence and continued to perform his swinging bebop until he was 92 years old when he announced his retirement. I spoke with his him in late 2012 when he had named an NEA Jazz Master—here are excerpts of that interview.

Lou Donaldson: First time I heard jazz was on the radio station, WBT from Charlotte, North Carolina, which was a country and western station. That's all they played. But…they had one disc jockey there, a guy named Grady Cole -- never will forget him -- and he had one record, Louie Armstrong and it was St. James Infirmary. And he played that every day because he loved that. And that's my first time hearing jazz music. And I liked it. In fact, I waited for that one record.

Jo Reed: As to what influenced Lou Donaldson’s own sound on the saxophone

LOU DONALDSON: Whenever I play a ballad, I always try to get a tone like Johnny Hodges, like he used to slur notes and sustain certain notes on his saxophone. And, when I tried to move through the chords, I would try to move through them like Charlie Parker. I heard him playing with Jamie Chan's band, and it was great. I never heard anything like that before. It changed my approach completely. Because I wanted to play like that. And I'd buy the records and wear them down to the aluminum. You know, they had an aluminum base then. And I'd play them so much I'd run, I'd wear out the record. So that's, that's about the style I played.

Jo Reed: Lou Donaldson moved to New York City in 1950—a great place for jazz. Lou became the house saxophonist at the legendary Minton’s Playhouse—one of the birthplaces of Bebop

LOU DONALDSON: We had about ten clubs right in Harlem where you could go and play you know, music.

Minton's was like a joint. It wasn't really a club. It was what we called a walk-in place. You know, you didn't have to pay anything. And, everybody came there. It was like a celebrity hangout, because you had people say, like Roy Eldridge, Billie Holiday, and Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan. They worked downtown. But their jobs ended at twelve o'clock or one o'clock. Minton's stayed open 'til four o'clock. So about two o'clock, all of them were there. You know, they'd come in to hear the music. And everybody would be there. It was great.

Best club to play in. Best club. I knew everybody. Never be another place like that. Not for jazz music.

Jo Reed: Lou Donaldson came on the scene pretty much at the beginning of hard bop And he’s thought and wrote about the transition from swing to bebop.

Lou Donaldson: Right. Most of the jazz before bebop was dance music. Normally, jazz was dance music. All the bands played for dancing. Every band played for dancing, very few bands ever played, like, concerts. Maybe Duke Ellington or someone like that once in a while. But everybody, Count Basie, Jimmy Lunceford… all the bands. All them played, they played for dancing. That's, that's what they were. Dance bands. The transition was that Dizzy and Charlie Parker had a new way of playing music, and it was a smaller group. Actually, what happened, they talked Coleman Hawkins into making a record with called Woody and You. It was written for Woody Herman. And that set everybody on that trend and started them playing that way and they played a lot of solos. In the dance bands, you didn't have many solos. You maybe had one or two and that was it. And you never had a drum solo but once a night. You'd usually feature the drummer one time a night and that was it no more. And it was great. It was great. But bebop you could play, everybody could play on every song. It was a different kind of setup.

Jo Reed: Lou Donaldson was one of the people, along with Art Blakey and Clifford Brown, who performed on one of the great live jazz albums, A Night in Birdland.

Lou Donaldson: Yes. It's the best, best-recorded session ever done live, yeah. It was a Blue Note date. Blue Note, Alfred Lion got everybody together and wanted us to make this date. What happened is he put Art on the drums and Horace, and myself. And I had made this record with Clifford Brown a year before then. And they liked Clifford Brown so well, they brought Clifford Brown in on trumpet. And, and Curley Russell on bass. And that's, that's the way it developed. But once we got to playing, the people were into the music. And Clifford Brown was so dynamic you, wouldn't believe. I would've played job for no money. This cat was great. To be so young and have so much stuff together at that age, it was amazing. He was amazing. And Art actually played well on that himself. So it was amazing, amazing. You got the energy, the projection from the music to the people, and you can hear it on the record. And it was great, it was great. It was a different kind of music. As anybody knows that plays music, sometimes you're just into it better, you play better. Same songs every night, but it's a different thing. Some nights a different thing.

Jo Reed: In 1958, Lou had a huge hit with “Blues Walk” in fact, it became his signature song. He explains how it came about

Lou Donaldson: Well, you won't believe it. I had a meeting with Al Lion and Frank Wolf. And I told them, I said, "Look, I'm not recording any more music with no, with any junkies. The junkies got to go." I wanna pick the musicians, I wanna pick the band, and we're going to make this record."

So I picked this guy, Herman Foster, who played piano. He was blind. He was singing in a church. But I had been playing jam sessions with him up at Carney's, and I liked him. And I picked Dave Bailey, drummer. Dave was a liquor salesman, but I had played some stuff with him and I liked him. And I got Ray Barretto on the congas. And the bass player I had was Peck Morrison who lived with me. I was living in a housing project at that time up in Throggs Neck in the Bronx, and he got in, and he was my neighbor, so he played the bass. And we made this record and it was a hit. I couldn't believe it.

Now Frank Wolf told me, it's the first record that Blue Note got on a jukebox from New York to California. That's a good tune. It's got a good groove, got a good groove to it. Good groove to it.

Jo Reed: One reason Lou Donaldson is such a dynamic performer is that he can read an audience—in fact, he’s known for that ability.

Lou Donaldson: We had what we'd call a "feel 'em out" set. The first set. Feel 'em out. When we went to a new place that we never played, we played a cross section of music. We played fast, we played slow, we played blues, we played ballads. Whatever the people responded to, that's where we laid. Then we'd sneak in a couple of bebop tunes and anything that we wanted to play. But once we got them in our pocket, that's what we did. It's amazing but music is like that

Jo Reed: His other great jazz innovation was a series of recordings with Jimmy Smith that popularized the organ-sax trio sound.

Lou Donaldson: That's it. That was it. Jimmy was a genius. Jimmy was a good piano player, too. But Jimmy was a guy that found that organ and found a new way of playing the organ. Like, like you could play a piano. Up until then, all those players, they didn't really play like piano players. You listen to Neil Budner, Wild Bill Davis, and all those kind of people, they play an organ a different way. But Jimmy played it like a piano. It looked like he was Art Tatum playing an organ. And he was great. He was great. And, my sound, we were very compatible. Yeah, we worked together without a doubt. We had two or three straight hit records, you know. Just like that. It was great.

Jo Reed: Lou also had a big hit with Alligator Bugaloo with NEA Jazz Master Dr Lonnie Smith on the organ—even this short excerpt will explain why

Music Up

Jo Reed: And Lou also played with singers including a stint he did with Betty Carter at the Audubon in New York…which came together in an unpredictable way.

Lou Donaldson: Right. And this is a story I'm telling you, now this is a story that you, you won't believe. I was working in Washington D.C., and I played from 5 to 8. And we had to come back to New York, we got to come through Baltimore which is about 30 miles away. And I knew that Miles was working in Baltimore. So I said, "Let's go by and catch Miles's last set." Saturday night. So I get there about 9 or 10 o'clock, no Miles. I see his band, Paul Chambers, Philly Joe, Red Garland, sitting out on the stoop with their instruments. And I said, "What? What's happening? Why are you sitting out here?" They said, "We're not playing, and the guy won't give us any money." I said, "What happened?" "Miles drew all the money up on Friday night." And they haven't seen Miles since. And naturally, they didn't have any way to get to New York. So I didn't have anything in my station wagon, so I said, "All right, put the bass and drums and things in there, and I'll take you to Philadelphia." Which I did.

And when I got to New York, Red Garland called me, said, "Man, we're quittin' Miles. We see you're working up at the Audubon, say, can we make a couple of weeks up there?" I said, "Yeah, of course you know." But I didn't have anyone but local musicians, so I put up this big sign: "Lou Donaldson with the Red Garland Trio." So many people came they didn't have the space. And so what had happened, I booked the place myself. I rented the place. I had rented it for the summer. And we played from 5 to 9 every Sunday evening. And the business got so good, I said, "We better bring in a singer." So I brought in Betty Carter. That's how she got there. In fact, she wasn't even famous then, because she sang straight-ahead music then. And her big number was "Perdido." And it was great, it was great. It was a great group. Great time.

Jo Reed: And what happened?

Lou Donaldson:Everybody made a lot of money and got famous.

Jo Reed: And here are some of Lou’s thoughts about his career.

Jo Reed: That is the late great 2013 NEA Jazz Master saxophonist Lou Donaldson. This has been our tribute to Lou and Roy Haynes, who both passed away last week. They are already missed.

You can go to their pages on arts.com to find more about their lives and their work. You’ve been listening to Art Works Produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. Follow us wherever you get your podcasts and leave us a rating! For the National Endowment for the Arts, I’m Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.

Jo: Here’s Roy Haynes

Roy Haynes: The Savoy, you can't hardly describe it in anything that you'll know about, you've got to have a great imagination. That was really an exciting period, because not only the people came to dance, some people would just stand in front of the bandstand and listen. They call that the "home of the happy feet" because a lot of people could dance like they were professional in those days, '40s, was when I first come to New York with the band. My first job, like I was saying, was at the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem. So it was a very exciting period.

Jo: And Lou Donaldson

Lou Donaldson: Minton's was like a joint. It wasn't really a club. And, it was what we called a walk-in place. You know, you didn't have to pay anything. And, everybody came there. It was like a celebrity hangout, because you had people say, like Roy Eldridge, Billie Holiday, and Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan. They worked downtown. But their jobs ended at twelve o'clock or one o'clock. Minton's stayed open 'til four o'clock. So about two o'clock, all of them were there. They used to come in to hear the music. It was great. Great.

Lillian-Yvonne Bertram. Photo by Adrianne Mathiowetz

Photo by Libby Lewis

Photo by Vance Jacobs

Photo courtesy of Anna Needham

2017 NEA National Heritage Fellow Ella Jenkins. Photo by Alison Green