Fabian Debora: NEA National Heritage Fellowship Tribute Video (2024)

Bril Barrett: NEA National Heritage Fellowship Tribute Video (2024)

Healing, Bridging, Thriving: Working For The Economic Well-being of Indigenous Artists

Jen Deerinwater (Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma). Photo by Eleanor Goldfield

Fabian Debora

Music Credits: “NY,” composed and performed by Kosta T, from the cd Soul Sand. Used courtesy of the Free Music Archive.

Jo Reed: From the National Endowment for the Arts, this is Art Works. I’m Josephine Reed.

Today, we’re kicking off Hispanic Heritage month and the National Heritage Awards with a conversation with 2024 Heritage Fellow Fabian Debora. Fabian is a celebrated Chicano artist whose murals not only tell stories of resilience and transformation but also shines a light on those too often ignored or scorned by society. A compelling artist, Fabian has achieved enormous success, with his work displayed in galleries, on public walls, and even on the ceiling of LAX. Growing up in Boyle Heights, Los Angeles, amidst the grip of gang life, drug abuse, and systemic hardship, Fabian eventually found salvation through art. His work portrays the struggles and triumphs of his community—gang members, the formerly incarcerated, and those seeking redemption—with an unmatched depth of compassion and authenticity. Because their struggles were his struggles. Fabian joined a gang, spent time in jail, but through it all, he kept on drawing and painting until he was able to turn a corner and with the help of Father Greg Boyle, founder of Homeboy Industries a pathbreaking gang intervention, rehab and re-entry program, he began to use his art as a powerful tool for healing and transformation, both for himself and the people he paints. And I’m so pleased to welcome him now. Fabian Debora, thank you for joining me and congratulations on being named a 2024 National Heritage Fellow.

Fabian Debora: Thank you so much.

Jo Reed: Fabian, tell me a little bit more about your early life.

Fabian Debora: Originally I was born in El Paso, Texas. And you know, in 1980, like every immigrant family, my parents decided to move to Los Angeles, larger city, bigger city for greater opportunity. And we arrived in Boyle Heights, Los Angeles, in the housing projects. Now, in the 80s, we considered it the decadal violence and crack cocaine epidemic and Rodney King trials, very difficult for a child to sustain his innocence during that decade. And so my both my parents tried their best being immigrants, they already had obstacles in place, and as a child, you know, you start to realize that things are not as comforting as they were when we were in El Paso, Texas. So initially, I started to feel a lot of disparities in my household, my mother and father trying to make ends meet, but it was now becoming heavy for me. And during those times, you know, I had to figure something out, as a child I didn't know what it was that was going on, I was only five years old, could not comprehend half the things that are taking place. So I would go under a coffee table that my mother had, and there I would pick up my notebook, and I would begin to create my own worlds to escape my reality. That's when I found art, the gift of art. And to me, it was more than just a gift, it held me and it gave me a sense of hope.

Jo Reed: Do you mind telling me a little about what was going on then?

Fabian Debora: Well, my father made some choices that started to neglect me, while he would go in and out of incarceration, and then having to deal with a single mother and her disparity, not knowing how she was going to make ends meet. So she put me in Catholic school, Dolores Mission Catholic School. And when I was at Dolores Mission, you know, I would bring the gift of art with me. And of course, you know, math was no longer math problems, I would turn those math problems into city skylines. So for example, two plus two equals four, four plus four equals a drawing, get up and go to the principal's office. Eventually, I got expelled from school for continuously drawing in class. Now, at that time, when I got expelled, you know, I kept finding myself not knowing why people weren't embracing my gift of art when it made me feel good. But of course, you have to do your school and academics, which I was going against the grain. But also, most importantly, I was coping through life with my art.

Jo Reed: Wait, can we back up…you were expelled for drawing in class…what happened?

Fabian Debora: So a teacher decided he'd take my artwork, put it in my face and he tore it in half. And in that moment, everything that I was coping through came back to the surface. I was so angry, behind the fact that he ripped the only thing that belonged to me and no one was going to take away, and so I got a desk and I threw it at the teacher. Now, that wasn't the way I should have reacted, but to me, art was something that was vital, that held me, and belonged to me, and no one was going to take away. Well, I got expelled. And of course, in that time, Father Greg Boyle, the founder of Homeboy Industries, he was just a priest in the rectory at the time, and so they walked their troubles over to-- across the street, and that's when I met Father Greg. I was 10 years old when I walked into his rectory at the church and he said to me, "What happened, son?" I said, "Well, this guy ripped my artwork and no one's going to take that from me, but me." And then he said to me, "Ay mijo, you're going to get expelled, son. I can't keep you at Dolores Mission, you're going to go to public school." And that's when I said "The lion's den?" And in that moment, he said to me, "Well, before you leave, son, I want you to do something for me." I go, "What's that, Father Greg?" "I want you to go home and draw me something." And for that moment, I was now seen. He recognized me for me, and he returned the gift of art back to me.

Jo Reed: But you continued act out and to struggle

Fabian Debora: You know, growing up in these environments of Boyle Heights and gang violence is not easy-- it's not an easy task for a young boy like me, so eventually, due to the abandonment and the neglect and not having my father present most of the time, I too made some choices that led me into gang subculture. At the same time, I started to experiment with drugs myself as a young man, and I leaned on graffiti art. I was then a graffiti artist, but that was also labeled as vandalism, which kept me from being creative. So continuously, then dead end after dead end after dead end, you know, I then joined the gang, which was the worst mistake I ever made.

Jo Reed: But Father Greg never gave on you….what happened

Fabian Debora: During that time in juvenile hall, they wanted to give me three years in youth authority. Well, at this time, Father Greg was now a friend of mine and he spoke up on my behalf, and eventually the judge said to him, "Well, if you're saying that this kid's got talent, then prove it to me." So my mother, gracefully, my mother always held my art, my drawings, she kept them in safekeeping and we were able to share these drawings with the judge. And then the judge then said to Father Greg, "Well, I'm willing to reconsider. He does have a talent, find them a location." And now this was like a trick question, because in the 80s, there's not many resources and so Father Greg's like, "Man, where am I going to go, or where do I begin?" And luckily, it is per design and through the grace of God that he called upon the East Los Streetscapers. The East Los Streetscapers are a Chicano mural movement company that was in existence at the time, and the great Wayne Healy and David Voteo, pioneers of the Chicano movement, opened the door and told him, "Bring him, we'll take him." And so I remember walking into Palmetto Studios at the time, I was about 17 years old, and when I walked through those doors, I felt like I was now in heaven of some sort, because when I walked in and Wayne and David received me, they looked at my work of art and they said, "You have talent." He goes, "The only thing we ask of you is that you pursue, stay grounded, stay focused, and continue exploring this gift of art that you're bringing towards us."

Jo Reed: When you think about that experience, that moment, what do you remember most?

Fabian Debora: So when I walked in, I looked at these walls and I saw these large scale murals. And in these murals, now I'm learning of my culture, my identity, and not only that, but the struggle, right? And I was able to learn in that moment that the Chicano murals gives you that freedom of speech that one can utilize to really convey a message, not only for self, but for the community. In that moment, I was now embraced by them, that the gang subculture gradually started to dissolve. And when I was learning of these murals, not only did I meet Wayne Healy, David Botteo, but I start to walk amongst the greatest Chicano muralists in LA, in Los Angeles. I then met George Yepes, Yolanda Gonzalez, Willie Herron, and these are pioneers. And for me at the time, I didn't really embrace who they were, I just knew there were someone in this world. And then eventually I held on to that, I learned the ins and outs of muralism. They gave me all the knowledge and wisdom that one needed in order to walk into this arena of the Chicano movement. And in that moment, I then said to myself, "I'm going to make a commitment and make it a responsibility to preserve this knowledge and this wisdom handed to me by the great pioneers of the Chicano movement."

Jo Reed: But you were still struggling with drugs, still in the gang life. You weren’t able to turn it around yet.

Fabian Debora: You know, I got the glimmer of hope, I got an essence of a path that I would like to pursue, and I was still consumed by trauma. So eventually I continued in this lifestyle, you know, in and out of incarceration, just like my father, but I never lost sight of that experience I had with the Chicano movement. And I just kept perfecting my skills, even in incarceration, I didn't let time do me, I did time by getting creative and envisioning and dreaming what these great paintings or murals will look like the day I'm able to grasp it. Fast forward, you know, after 15 years stuck in a revolving door of suffering and misery, in between still creating art, I decided to redirect my life. And in that, I got the help that I needed and art was always at the center. And I came home, I came back to Father Greg at the age of 30, and I came in with one vision and one mission. And I'm about to reclaim the responsibility that I have as an artist and preserving the Chicano mural histories, oral histories, and in the movement that it must continue. So I started picking up the paintbrush and I start to get creative and I started to now really unfold my story.

Jo Reed: Your murals and paintings often portray your story, gang members, what we would say are marginalized people, and you show them with an amazing amount of tenderness and love and humanity.

Fabian Debora: Absolutely. And I think that is what I like to invite the world to see, because in this lifestyle, you know, we are human beings before anything. It is through societal, systemic infrastructures that at times make it difficult for us to even foresee that there is a sense of future. But at the same token, it's also due to the trauma and the absence of hope, and things that are missing in our lives that we don't value ourselves enough to know that we do, and we should, belong to this world in the way that we are made to be. And that's why, you know, not only is it a responsibility, but it's important for me to help and make the world a safer place by sharing the narratives of the people in my community so that they too can see the humanity and make connections in ways that is going to compel them enough for the stereotypes to be removed.

Jo Reed: Well, your work also often incorporates religious imagery as you're depicting gang members and marginalized people. Tell me what you hope to do by combining these two different kind of imageries.

Fabian Debora: I think for me, when I think about my responsibility, I have made it where I utilize the common themes of identity, culture, religion and gender. For it is said that we are all one and should be all one in the image of God, in a sense. And then you realize that sometimes these institutions have not quite reached that image of God. And so when I utilize imagery of Catholicism, I'm also inviting the church to recognize, you know, the image of God and the human beings that we are, regardless of where we come from. And I do it in such beautiful and sensitive way, embracing what the religion elements have done for my mother and my father at the same time. It's not a competitive approach, but it's a welcoming approach, and hopefully through religion, we can also get to a dialogue and a conversation of compassion and understanding for the redemption that we seek behind the choices that were pretty much in place sometimes. Because, you know, when you're a kid, if they can give you a manual that says, okay, what type of father would you like, what type of mother would you like? Check the boxes. It doesn't work that way, you pretty much are given the cards you're dealt and have to make the best of it. But, you know, when I utilize these images is with hopes that we can all come together as one, regardless of our beliefs, regardless of who we pray to, but really to just get to the core of a conversation and find God in all people.

Jo Reed: Well, as you say, you describe your work as embodying the voices of the voiceless. And can you just talk a little bit about what it means to you to give visibility to people who are so frequently unseen?

Fabian Debora: Absolutely. I think, you know, a lot of the times, you know, due to the trauma and most of these young men and women, or even men and women, formerly incarcerated, have suppressed their own voice. And sometimes it makes it difficult for them to foresee that they, too, can help make the world a safer place. And for me, it's about utilizing the power of the arts as windows and portals to really signify the social injustices, but most importantly-- most important, the resiliency that comes from these folks. At the same time, I believe that the more you paint these images, the more that it will begin to soften and remove the stereotypes. And it's amazing to see that when I create art, I utilize real people from my community because when they see themselves in this narrative or this storytelling that I'm conveying as an artist, two things happen. Not only do they feel seen, valued, but they feel important now being part of a story or a narrative that's going to help the world become a safer place. And so it's a ripple effect of transformation, not only for myself as an artist, but for my community, and the subject matters that I utilize to help me tell that story. That is Chicano. That is Chicano murals, and it has been in this way for decades.

Jo Reed: Well, you are enormously successful as an artist. Your art is spectacular. Really, I cannot say enough about it. And you've even painted the ceiling of LAX, which, of course, is such a testimony to your talent and your vision. And as a Los Angelino, you must have felt so proud. I know I would have.

Fabian Debora: Oh, no, absolutely. And I think, you know, my job or at least my responsibility continues to keep inviting folks, right? So the fact that I was given this opportunity to be in the LAX, regardless of my past, regardless of my past history and who I was, when these opportunities arise, it's exactly what we seek and we call on for, so that we can really open the door broader for the next generations to come with hopes that they, too, can find themselves creating in such spaces and places. So the fact that many eyes are going to walk through the LAX and see my own my own little Sistine Chapel, I would say, yeah, it made me just like, yes, it is possible. And it can…

Jo Reed: What did you depict on that ceiling?

Fabian Debora: It was called "Inner Self, Inner Voice," I think I was inviting the passengers, when you walk into the-- it was a homeboy bakery. And so I wanted when you walk in, you have these beautiful eyes gazing on you, and that is the invitation to go through your inner self. And when you walk out the building, we hope that you can find your inner voice. Folks, sometimes as human beings, we're too busy looking outward, but the minute you begin to look inward there you find your gift, your strength, and then your voice can become amplified. And that was the idea of this mural.

Jo Reed: You had a recent series, “Cara De Vago.” And that draws inspiration from the Italian Renaissance, particularly Caravaggio. Talk about what inspired you to do that and how you merged that artistic tradition with the lived experiences of your community.

Fabian Debora: No, absolutely. And I think, you know, for me, in 1994, back when I was a young one, I went to Rome, Italy. Father Greg was able to send me to Rome. And when I went to Rome, I went to paint a mural. It was a big conference and convention with New York, Chicago, I represented Los Angeles as a young man. And we did this, I think it was like a 200 foot long wall where we all came together, all this intersect, all the cities, and we did this beautiful mural. While on my visit in Rome, I was also standing in front of the Pieta. And when I stood in front of the Pieta, I was staring almost as if an out-of-body experience was taking place. And I'm staring at Michelangelo's original Pieta, so I can feel this vibrancy and energy that was being received by me, and at the same time, admiring these beautiful Renaissance, Baroque style works of art. And then I got a thought. I said, "As much as these beautiful works of art are well received and embraced by museums, they still don't reflect my community or me." So that was the initiation, back in 1994, and I never lost sight of that little impact that I discovered in Rome. Fast forward now that I am at a different place in my career, I revisited that and I said, now I'm ready to paint my own Renaissance, Baroque styles with the influence of Caravaggio. Also, if we understand Caravaggio's story, he was made to be an outcast. Caravaggio was also a controversial artist, not many people like him due to those stories told of him. And so if he was an outlaw, and I was considered an outlaw. But if Caravaggio found his spirituality through his art and I found my spirituality and healing through art, perfect match. So I said, Cara de Vago. Instead of Caravaggio, I said Cara de Vago, which is face of a vagabond, a wanderer, and that's who I was. So I was able to take Caravaggio's stories and re-tailor them to correspond to the lived experiences, not only of me, but the people that I work with and also to invite religion, right, as a way that Caravaggio did so that they can foresee these homeboys and homegirls in a different light, and a more welcoming light. And then hopefully get to the dialogue that is going to bring upon healing and connection of humanity for the people.

Jo Reed: You know, art has been a lifeline for you, and now you use it to help other young people and older people, too, people who have been incarcerated, former gang members. Homeboy Industries was started by Father Greg . And it was there that you founded the Homeboy Art Academy in 2018. What inspired you to create that space devoted to art?

Fabian Debora: I think, you know, when you compare it, when you when you sit back and reflect all the blessings that one receives and regardless of how dark one's life was, I said, "How can I fulfill a need?" "Now that I've gained access, how can I give access?" And I know that there's still a lot of young men and women in my environments who have the talent and the gift of art, but don't have the means or the financial support, or just even the platform. And so to me, I say, you know, "I'm going to develop and create an academy." And this vision started in 2008, which was under Somos la Arte Art Academy, and because of my lineage and my own connection with Father Greg and Homeboy Industries, I have always wanted this to be part of Homeboy. Eventually, it took the timing that it needed to take, and finally, in 2018, it officially became a new entity of Homeboy Industries, and this is how we fulfill the need. Not only have I been successful as an artist, I have healed and continuing my transformation, but now I'm paying it forward, just like the East Los Streetscapers did on to me when I was a youth back when. And so I'm only reduplicating the importance of mentorship, receiving and welcoming spaces so that these young men and women can also hopefully redirect their life through the power of the arts. And that in itself is what makes me, I think, unique from many other artists. I don't arrive and then come back for folks, I walk alongside the folks so that together we can reach our destinations, whatever that may be.

Jo Reed: The Homeboy Art Academy is a trauma-informed arts center. Can you discuss the healing process that happens when people engage in art, especially people who have experienced incarceration or gang life, who have had really difficult circumstances and they're putting it behind them?

Fabian Debora: Well, absolutely. I think here at the Homeboy Art Academy, we don't live by the labels that are constructed sometimes to create a divide. So a lot of these young men have been oppressed and suppressed due to their mistakes or to whatever the life-- the lifestyle that they have chosen. But here we welcome it all, we utilize the universal language in the name of arts. What someone might consider gang writing, we see it as a creative, unique form and style of letters rather than continuously reinforcing those labels that remove them from being in this art world. But not only that, it gives them the confidence, it builds them up to believe and know and understand that what they bring to the table is as much art-- and they are a work of art. And the fact that they are being seen, embraced in community begins to dissolve the belief system and the mindset that keeps them from being their true selves. And here we embrace them through multiple arts disciplines, we have Mondays, we'll do like visual arts, every form of visual arts you can imagine. Tuesdays, we do intentional healing circles where we invite indigenous traditional arts practices. Wednesdays, we'll do music production and engineering where they can unfold their narratives and stories through music, and compose beats, play instruments, for example, if that's what they want to pursue. On Thursdays, we fluctuate whatever the art discipline. So it would be photography, film, we also do creative writing, you know, poetry. And then on Fridays, we're also introducing them to the virtual reality world, anything with technology, coding, also graphic design, multimedia, Photoshop, InDesign. So we have a whole menu of arts disciplines here that can really embrace the participating youth and adult with hopes they can walk into the creative economy. So I always said that back then my mother had a choice, she either had to buy eggs and milk or pay for an expensive brush. And most of the time she had to go for the eggs and milk, so I had to figure out how to get tools to do my art. But here at the Academy, everything is available and all our services are free so that there is no excuse for creativity.

Jo Reed: You’ve known Father Boyle since you were ten. And you share his mission of healing and transformation. In fact, you illustrated his book, Forgive Everyone and Everything, didn't you?

Fabian Debora: Yeah, it was Forgive Everyone and Everything, and I remember when Loyola Press reached out to me and they said, "Hey, would you like to participate?" And we can utilize all your work and corresponding or in alignment to Father Greg's literature or, you know, writings. And I said, "Yeah, absolutely. Of course, what an honor it would be," you know what I mean? And when the book was published and we saw the final and I opened and turned the pages, I was in awe at the fact that my art really complemented Father Greg's writing, and his writing only amplified my works of art. So we did a podcast, Father Greg and I, and they asked me a question, you know. "So Fabian, what do you think about this book," similar to what you're asking? And then I said to them, "Well, Father Greg, I don't know if you would agree, but it feels like a match made in heaven." And we both started laughing out loud from our lungs. And that's the beauty, right? How writing and art combined together, the power of it, is beautiful. And it was a book, well made, and it's something that I admire and hold to heart because here it is, something tangible that has been documented with Father Greg. That's an honor.

Jo Reed: And it really is, it's as though you're in conversation with each other. It's wonderful. You, as we said, have been named a 2024 National Heritage Fellow. How did you feel when you received the news?

Fabian Debora: I mean, I think and I'm getting the chills right now as we speak, because when you work hard and you're committed, and you hold on to that belief of that we too belong, and that we too, regardless of our past, can make the world a better place, and then you get a call from the NEA. That in itself is just goes to show and demonstrate that there are people who are watching, right, and that they are really acknowledging, you know, and all that hard work, sweat and tears, you know, lonely nights and stressful days as an artist in the studios. But yet the love and the compassion that one retrieves in working with these folks, I know the NEA has helped seal the deal in a way that it's only going to help not only for me as an artist, but most importantly, it helps me in my mission and vision to demonstrate to the people that I work with that things are possible, bro, it is possible. And if you just stay consistent in your belief and your passion in the arts and helping others and giving of yourself and also while preserving the Chicano mural history, here we are, the National Endowment of the Arts. How about that?

Jo Reed: How about that! And I think that is a good place to leave it. Fabian, thank you for giving me your time and so many congratulations for an award that is deserved on so many different levels. And your work is beautiful.

Fabian Debora: Thank you so much. And I'm glad that I'm able to share my life and also the importance of the arts to many. Thank you.

Jo Reed: Thank you. That was Chicano Muralist and 2024 National Heritage Fellow Fabian Debora. Tonight, Tuesday, September 17 at the Kennedy Center in DC, the NEA will premiere short documentary films about each of the National Heritage Award recipients, including of course, Fabian, followed by on-stage conversation with each of the Fellows about their culture and art. And tomorrow, Wednesday, September 18 at the Library of Congress, each Fellow will be honored at an awards ceremony. Both events are free—you can get more information at arts.gov. And if you’re not in DC, don’t despair--both the film screening and the ceremony will be webcast at arts.gov/heritage.

You’ve been listening to Art Works produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. Follow us wherever you get your podcasts and leave us a rating!

For the National Endowment for the Arts, I’m Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening

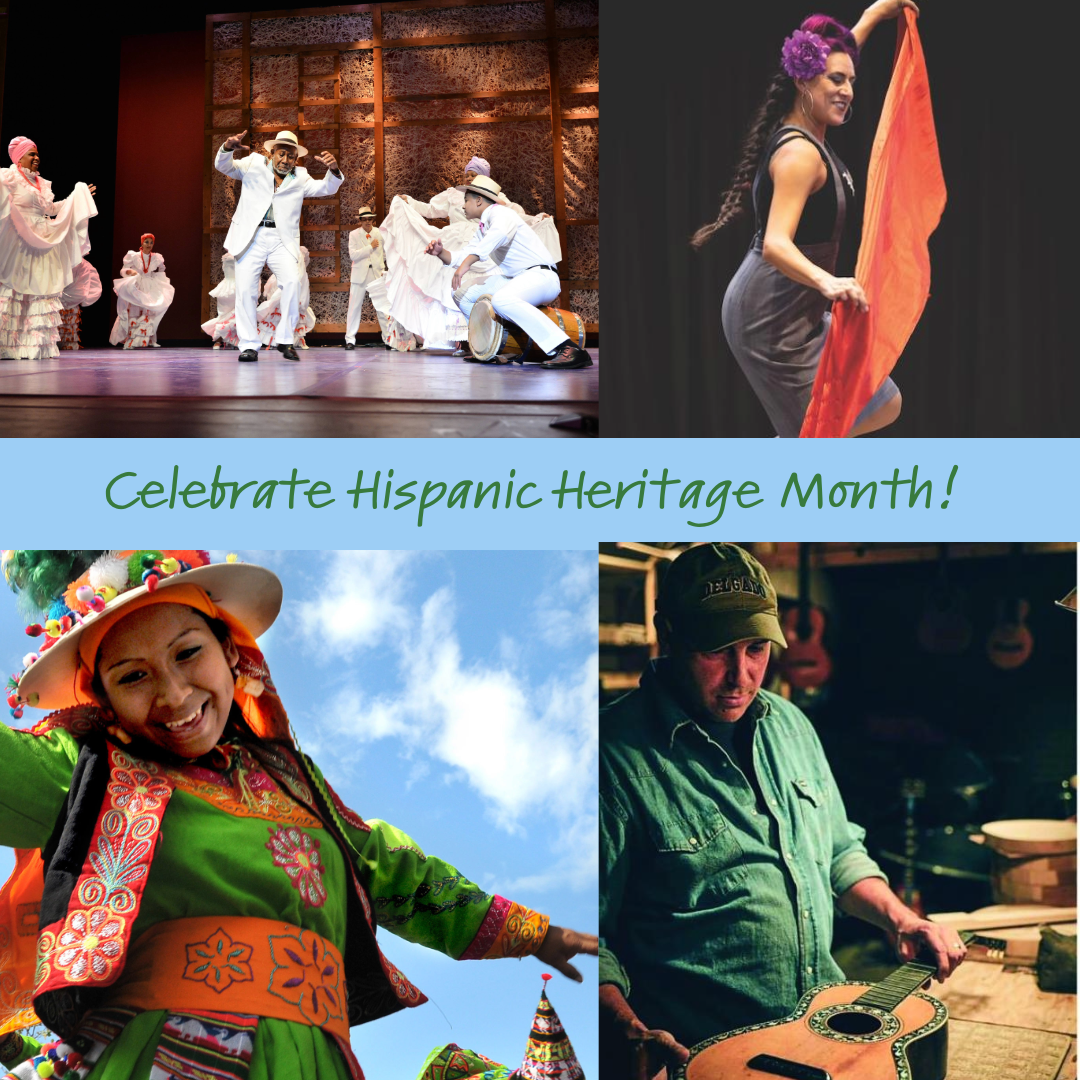

Celebrate National Hispanic Heritage Month 2024!

(clockwise, from top left): NEA National Heritage Fellow Modesto Cepeda performs at the 2017 National Heritage Fellow Concert. Photo by Tom Pich; At Jacob’s Pillow in August 2022, Vanessa Sanchez and her ensemble La Mezcla performed selections from Pachuquísmo. Photo by Danica Paulos, courtesy of Jacob’s Pillow; Luthier Manuel Delgado with one of his guitars. Photo courtesy of Delgado Guitars; A dancer at Fiesta DC! Photo by Rafael Crisóstomo

Sneak Peek: Fabian Debora Podcast

Fabian Debora: Due to the trauma and most of these young men and women, formerly incarcerated, have suppressed their own voice. And sometimes it makes it difficult for them to foresee that they, too, can help make the world a safer place. And for me, it's about utilizing the power of the arts as windows and portals to really signify the social injustices, but most important, the resiliency that comes from these folks. At the same time, I believe that the more you paint these images, the more that it will begin to soften and remove the stereotypes. And it's amazing to see that when I create art, I utilize real people from my community because when they see themselves in this narrative or this storytelling that I'm conveying as an artist, two things happen. Not only do they feel seen, valued, but they feel important now being part of a story or a narrative that's going to help the world become a safer place. And so it's a ripple effect of transformation, not only for myself as an artist, but for my community, and the subject matters that I utilize to help me tell that story. That is Chicano. That is Chicano murals

American Artscape Notable Quotable: Heather Fleming (Diné/Navajo) of Change Labs

June 2023 grand opening of the Tuba City Entrepreneurship Hub. From left to right: Council Delegate Otto Tso (Diné/Navajo), Change Labs executive director Heather Fleming (Diné/Navajo), Navajo Nation President Buu Nygren (Diné/Navajo), Change Labs co-founder Jessica Stago (Diné/Navajo), Change Labs Board Chair Brett Isaac (Diné/Navajo). Photo by Jesse Wodin

American Artscape Notable Quotable: Chantelle Rytter, Atlanta Beltline Artist

The 2017 Atlanta BeltLine Lantern Parade marches along the BeltLine’s Eastside Trail. The parade first began in 2010 and has become an annual staple since its inception, with thousands participating in the family-friendly event annually. Photo by the Sintoses, courtesy of Atlanta BeltLine