“NY” composed and performed by Kosta T from the cd Soul Sand, used courtesy of Free Music Archive

Elizabeth James-Perry: In spite of the fact that we're living in the 21st century, and we're so technologically advanced, I think humans are, and will always be, social creatures. And I think we'll always crave things that don't strictly serve a purpose, but that are also engaging and intriguing and interesting on a different level, other than its strict usefulness. And so I think that there's always going to be arts and culture. I think it varies a bit, in terms of practice and ease, and I think that whether you come to it when you're older, or you just grow up with it as a constant in your life, I think that being able to gather together and share knowledge, share artistic practices, make beautiful, unique things that relate to your culture, and then gift them in your tribal family and tribal community, or exchange with other tribes at various events, is really valuable.

Jo Reed: That is Wampum & Fiber Artist and 2023 National Heritage Fellow Elizabeth James-Perry. An award-winning and internationally known artist Elizabeth James-Perry is an enrolled member of the Wampanoag- Aquinnah Tribe in Massachusetts. And that affiliation with its history on the land and with the ocean informs all of her work. She creates her art-- wampum shell-carving and bead-making, porcupine quillwork, and twined textiles--using traditional tribal methods, hand tools and materials. Following years of research and gardening, she was able to successfully revive natural dye techniques using native plants she either grew or harvested sustainably herself. The result is artistic work of great beauty and deep significance which has been commissioned by museums both here in the US and abroad. Holding a degree in Marine Science, Elizabeth worked for many years as a Senior Cultural Resource Specialist within the Aquinnah Tribal Historic Preservation. She combines traditional tribal ecological knowledge, art, and science to create dazzling pieces of art and bring attention to sustainability and Native lifeways. Her long commitment to teaching and mentoring emphasizes artistic practices through traditional knowledge, connecting identity and sovereignty, maritime traditions and restorative Native gardening. I spoke with Elizabeth James-Perry soon after she was named a 2023 National Heritage Fellow—here’s our conversation.

Jo Reed: Well, Elizabeth, I want to begin by congratulating you at being named a 2023 National Heritage Fellow.

Elizabeth James-Perry: Thank you. It was quite an honor.

Jo Reed: You are a multimedia artist and you work with wampum and fiber and gardens and all your work is tied to your Aquinnah homeland. So why don't we begin there and why don't you tell us about your traditional homeland, beginning with where it is.

Elizabeth James-Perry: Certainly. I'm enrolled with the Aquinnah Wampanoag tribe and our tribal community is on Martha's Vineyard in what used to be called Gay Head but we've renamed it to our community name of Aquinnah. We live on the headland of the island, so it's in the southwest part on the high end at the cliffs. And it's a really scenic area with multicolored cliffs that are really unique in the world. There's no other place quite like it and so it's a really distinctive place to be. I grew up close to my homelands in Dartmouth, Massachusetts on the mainland, so I'm a few miles across the water and I can essentially look out towards the Elizabeth Islands from the beach here and I can see the smaller islands and through it-- through them, I can see Martha's Vineyard.

Jo Reed: Well given that location, there's a tradition of living with and harvesting the sea. And the sea is vital to your history, to your traditions. And how is it reflected in the art that you make?

Elizabeth James-Perry: You know, our ocean heritage, I think, is reflected in my art in that I was raised with a combination of family history and storytelling and whaling adventures and misadventures being related. You know, along with an introduction to the coastline and different places of significance and just very much at home in the beauty of the Atlantic Ocean. So the water is as much our homeland as the land is, if that makes sense. And it's a great inspiration to a lot of Native art on the coast. We use shells in our art in creating traditional beads of wampum. We use a lot of other marine resources as well and it's a big part of our daily sustenance in terms of our diet and life ways, too.

Jo Reed: And wampum are beads made from shells and the shell you tend to use is the quahog, which is a clam. Tell me about the unique aspects of quahogs and why they're ideal for wampum beads, or the ones that you make, anyway.

Elizabeth James-Perry: Yeah. So, yeah, traditionally, for time out of hand, wampum has been made from the quahog shell and I think that ties into a few different things. One is that it's a bivalve clam that's relatively abundant here on the coast in shallow waters. It grows to great age, which means it also grows to a good size and a good thickness, so it's a good thick serviceable material that's very durable. And so, because it's almost as hard as stone, you have to put a lot of work into shaping it; however, once you have, because it's such a sturdy material and it's not friable the way that, say, oyster shell might be, or breakable, the way oyster shell might be, quahog is worthwhile investing the time and creativity in to create beads, to create pendants and different designs to honor different aspects of creation or treaty agreements, histories, just creative pieces for everyday adornment as well. You know, artists have a good eye and I think that was true many thousands of years ago when folks were looking for materials to use in their expressive culture. And so, when you're looking for materials for your weaving, for your dyes, for your jewelry, for diplomatic use, wampum really fit the bill. The shell also has this beautiful purple region. It also has white regions or sort of off-white kind of cream, sometimes, rarely, a little bit yellowish regions as well and that duality in color means that you can create beads in the two different colors and make these high contrast designs that are very visible from a distance. And so if you're convening thousands of Native people for perhaps a celebration or a ceremony, perhaps a traditional ballgame, important council meetings, that is something visually that's going to be very striking and communicate very easily.

Jo Reed: And you use traditional methods when you're shaping the shell. Will you walk us through the processes that you use? You begin by gathering the clams themselves.

Elizabeth James-Perry: Sure. There's always going to be an aspect that's traditional even if you're using modern tools. I think partly because it's a living animal and the shell doesn't just jump out at you, you have to go and find it. And so the first step is actually knowing the environment, knowing where the water is clean enough to go and dig the clams and being selective in that, you know, the small ones aren't really going to afford you the ability to create a good thick-walled really strong bead. So you kind of have to be selective in the size of shells that you're using. So I use what they call the bulls. <laughs> So the quahog that you eat out of those shells is not tender. It's the kind that you want to chop up and definitely put in a chowder or maybe cook up in some clam fritters. And so then, you have a look at your shells. You decide if some are thick enough to really support good, thick, old-style disk beads. You put those aside. Then you've got to be thinking about your patterning in the piece that you're creating. So if I'm creating a belt of a certain size, I have a rough idea in my head, "Oh, I want it, you know, I want so many rows because I need the space to be able to realize the patterns that I need. I need it to be X long." So I'm looking at making at least 350 beads, if not more, even though I might not use all of them, because some of those beads might be too small, some might break in the actual manufacture, some of them, the color might be off. So there's a lot of selectivity in the artistic process that has to happen too, to realize a really nice piece. Each piece is really unique because each shell is really unique and the patterning is really unique. And it keeps it from getting too repetitive or too boring.

Jo Reed: How do you work with the shells to shape them into beads?

Elizabeth James-Perry: So when you have the shells, if you're doing it the traditional way, you use a stone saw. You know, my brother is a really good flint napper. I'm not a toolmaker. What I'll do is I'll go in certain areas like the Connecticut River Valley has beautiful, you know, chunks of sandstone that have been polished by the river for countless, you know, hundred thousands of years, and so there's naturally-shaped pieces that are just great working surfaces. There are great narrow pieces that are almost like a natural file, because it's a long, slender piece and it's already abrasive because it's sandstone. And you know, you can use other stones as well. You can use local granite that's been polished on the coast as a work surface. So basically, you're taking that shell and you want to remove the rough back and you have to abrade it off. So you have to decide if you're going to use, like, sandstone and water and a lot of elbow grease <laughs> to grind that down so that the back is off and you simply have the workable sturdy part of the shell and it's not rough anymore and liable to scrape you. Or you can take some sand, even sand of different texture, if you want to get down to it works really well. So you might have some coarse sand to begin with and finer sand or sand you crush down on purpose at the end. And you want to add water because the water is just going to make those tools work better. Your tools will last a lot longer and they won't wear out as quickly. And likewise, and they'll work faster. It's also going to have the added benefit of keeping that dust down because if you want to make hundreds of beads, you know, my ancestors worked outside on projects like that, so that's summertime work, you know, when it's nice and comfortable outside, or maybe spring and fall as well. And then, of course, wintertime is a wonderful time for doing a lot of the spinning, dying, weaving of wampum into belts, although that was flexible as far as need or ceremony or maybe a council was happening. So in our traditional ways, back in the day, the women had the responsibility of encircling the council and memorizing all of what was said and all of what was agreed upon and then going back and weaving that into belt form to record it and they were responsible also for sharing that throughout their extended clans or families. And so that's a lot of responsibility. There's also, of course, women who are in council as leaders and things like that, too. So there's a pretty strong association I think in some ways with women and wampum. It's a really time-consuming art and by no means do just women make wampum beads. I think men and women both made wampum beads and in the historic period, of course, that got changed and kind of caught up in colonial ideas about taking over and using wampum as money and paying other tribes, you know, as well with our wampum too, so kind of intensifying production and making it dangerous is think to keep belts and to keep even woven wampum that was not necessarily strictly ceremonial or governmental but also personal family heirlooms and adornment. You know, your grandmother's beautiful collar that she left you or something like that. People were robbed and sometimes killed, you know, for their wampum. It's kind of a sad history, but I think it's important to understand that we still have those traditions now, so at any point people decide that they want to spend a lot of time working on wampum and reviving those traditions and the associated observances, I think that that's a possibility. We're still here in our homelands and we still have an ocean.

Jo Reed: I'm curious what drew you to create wampum, art with wampum and to do it using traditional methods. Was this something that you came to as an adult? In your childhood home, was that kind of traditional creativity happening when you were growing up?

Elizabeth James-Perry: Boy, that's an interesting question. It's very analytical, <laughs> in a way that, you know, there's definitely choices that artists make, right, about their career path that they're going to follow. And probably the things that are important to us as artists don't, you know, figure in the public's radar at all and probably what's important to the public-- it's not central to Native artists' decision making and our ways of teaching in our families and stuff. I think, so the central things that I feel guided me when I was growing up here in Massachusetts was the importance of being connected to tribal homelands and either staying in the tribal homelands or staying near them or visiting often. So I have family members who did, you know, all of the above. And I, you know, come out of people who traveled the world in the whaling days. Folks were also in the Navy and, you know, they were merchants and things like that, also traveling the sea. But there always was just such a strong sense of home and community and staying connected. So the importance of homeland and this region and nature in shaping sensibilities, tastes, the way the light is different times of year, because we have these wonderful seasons in New England and you know, something so beautiful about that cold winter light, you know, in the wintertime on a beach, on the dunes and on the grasses. And there's so many really fond associations, I think, of coastal living. You know, it's coveted. It's restorative and it's beautiful for your spirit. There's something about the ocean that's really mysterious in that way and you know, quite comforting and really valuable in ways it's hard to articulate. You know, maybe as a tribal person, that was emphasized more so. It was "This is central to your identity. We enjoy visiting family. It's important to stay in touch. It's important to be connected to your roots."

Jo Reed: What about in your home—Do you grow up art being created around you? Were you encouraged to take up art?

Elizabeth James-Perry: And then I was sort of free range allowed to kind of explore whatever arts I wanted to, you know, but inspired, I think, by what I was seeing in my house, you know. So I grew up with, you know, my mom, Patricia Perry, who is a member of the James family from Martha's Vineyard, and she somehow when my brother and I were very little, she was practicing scrimshaw and she'd also do illustrations. She also liked clay very much. So she was quite talented and very modest. And I don't think she ever gives herself credit for shaping me and Jonathan's aesthetics at all, but, you know, it was very central. And so I think she didn't grab wampum and say, "Here. You need to work with that. Here, I'm going to show you how to do everything with wampum." She had an appreciation broadly for Native arts and had grown up when more so bead work was very popular. And she was very interested in scrimshaw and that's what she pursued and she continues it to this day. I was never told, you know, "Oh, go into weaving. Go into basketry. You should do natural dye work. You should do wampum." I watched her work and I participated in some of her art to the degree that I really got comfortable with natural materials and textures. I also had a more realistic sense, although I had to really work to embody an appreciation of that, that things made with the hands take time. You know, it's not about instant gratification. It's not like picking up a coloring book and filling it in or something like that. There's a depth, there's a selectivity that you can only get from experience. You can have teachers and mentors. Maybe you can do research. But how well you do is really kind of governed by how much time you're willing and able to put into your particular craft. Wampum resonated with me and I don't know if I'll ever be able to fully express why. It just, it was very striking. It was rare. It was very beautiful. It has a unique texture an appearance. Purple is not the most common color in nature in terms of materials to carve and yeah, I mean, it captured me and then I think I really went in-depth and got much more technologically adept and sophisticated when I decided to focus on 17th century history and diplomacy and I started to really look at and read about wampum. And it just seemed like the more that I knew, the more I realized there was more out there to learn and it was just so deep and rich and so full of cultural heritage that I essentially became hooked. And that would be, that was probably around 20 years ago. You know, an artist is drawn to I think a certain appearance, I guess, or aesthetic in their art that they want to express. And, you know, for me, I think the three-dimensionality of what you can do with wampum, what was done historically, let's say, and even, I guess I'm going to use that controversial term "prehistorically," in ancient times with wampum, there's a wonderful three-dimensionality. There's a preservation of the shape of shell and the thickness of shell and the substantial qualities of quahog that make it so striking that really appeal to me and if you have a sensibility, if you're a creative person and you don't want to do the same thing over and over again super quickly, just to be efficient about it and move on, and you just really get off on the process, artists can be very tactile and there's something about really being hands-on, really holding the shell, knowing the weights of the shell, which is quite striking, looking at the variation in the layering of the color that's this living being created over time and cutting through those gradually and exposing and exploring gradually, there's something about a relationship that you can really explore fully if you give yourself time. And I think what machines can do if you're not very, very careful in your relationship to machines and computers, is they can speed everything up and that efficiency can be pretty seductive. But I think that efficiency can also strip away depth and feeling and experiences that otherwise you might take the time to have and to learn from and hold with you.

Jo Reed: Elizabeth, you're also a marine biologist. How does that work mesh with and inform you work as an artist?

Elizabeth James-Perry: So Marine science really resonated because I think tribal folks are still so interconnected with and interdependent with the Atlantic Ocean and it's such a vital force in the Northeast. I think we have a front row seat, seeing how fish are doing, whether or not they're thriving or whether they're suffering. Whether shell fish are thriving or suffering. We've seen, you know, obviously, the decline of the whales with the commercial whaling industry and then to some degree, I think, their return. The Marine Mammal Protection Act and the return of now of some seals to this region, it's pretty remarkable. And so I think the tribal mores of responsible stewardship, staying in connection with the resource, looking at what's going on and really modifying interactions, not overharvesting. Those are really key parts of longevity of tribes in their homelands. That's why we can park in an area for tens of thousands of years, and life will continue just fine. There might be some changes in adaptations as climate changes, but we tend to continue in spite of all of that, and in spite of colonization, as well. It just gives you a different kind of time frame, and the ability to plan for the future, and think about how your actions impact the resources. You know, observation is also a key part of science: long-term commitment to monitoring, seeing what's there, versus what would be easy to assume. There's a difference between knowing and assuming, and I think science gives you that opportunity to observe and record what's going on, and to make recommendations based on what's going on in a way that is most helpful to the resource, essentially. And that is also, although it's articulated in a different way, a really key tenet of Native land stewardship and ocean stewardship, as well. So I find the two are highly compatible, for my purposes.

Jo Reed: You're also a fiber artist, working with a variety of natural material, and I'd love to have you talk about that work, because you've been credited with the recovery of this lost art. So, talk about the recovery of the processes of making your fiber work.

Elizabeth James-Perry: You know, I think things become lost because lifestyles change, and people make certain decisions, or have to make certain decisions. I think that, in terms of the fiber arts, there were still folks in tribal communities on Martha's Vineyard, although it wasn't common, still hand-processing Indian hemp and milkweed for cordage, and then doing weaving for our own communities, for our own use, because it was valuable, and it was handed down, mother to daughter. And they were treasured pieces. And then gradually, as more folks became disenfranchised and perhaps had to move, or had to move to cities to get jobs year round, or get educations, or maybe there was world war, and so they went overseas, there was a lot of disruption. And then there was also sort of this quick change-around to a very different lifestyle, where there weren't mainly households using a lot of handmade things, whether they made it or bought it, but plastic material cultural became just ubiquitous. And it was quick, and it was very inexpensive, and... a lot wasn't being supported, because you could just get these things cheaply. Why would you support artists making these things by hand? Why would you restore the environment to make sure that artists still had natural materials to work with? So, there were increasingly challenges, I think, to pursuing those. But my-- you know, my great-grandmother's generation still practiced those arts, and things like that, to some degree.

Jo Reed: How did you learn fiber art—who taught you?

Elizabeth James-Perry: I grew up with cousins who were older generation. Their mothers were older. My weaving teacher, Helen Adequan [ph?], her mom, also named Helen, she was born in the late 1800s, around folks who were still doing a lot of those things, and she was a really great basket weaver. Her daughter was a really good basket weaver. They knew how to make mats, which was a form-- for some reason, that Tudi [ph?] form really fascinated me, visually and texturally. And so I got a lot of guidance from them, from-- pardon me, from Helen Adequan, not from her mother. I remember her, but she died when I was young.

Jo Reed: What do you remember about their teaching—what stood out for you

Elizabeth James-Perry: They were uncompromising, so I don't think that they were just turning out tons of baskets, but the ones that they made were creative and beautiful, and the materials were really carefully prepared in such a way that, decades and decades later, the baskets were still in amazing condition. And someone had taken the time in the twining process to twine a little chevron -- a horizontal chevron design-- that was really subtle. So, really, if you were a weaver, and you took a good look, you'd really appreciate the pattern and the extra work. But the casual observer, even who had it in their house for decades, really didn't have a clue. So it was obviously art that was being preserved by the maker, for the maker, and not necessarily seen or appreciated or valued by the general public, or even sometimes the tribal public. So I think that they were folks that were doing what resonated with them, what was important to them, even though there wasn't necessarily a lot of societal rewards <laughs> for doing so. I think that that informed what I was doing, you know? And I think that, at times, I've been able to make it a more social kind of undertaking, when I've gone to powwows with my weaving, and then folks come around from the tribal community, from the broader region, and say, "Hey, that's a beautiful finger-weaving. Can you teach me how to do that stitch? I'd like to go make myself a sash." Or, "How are you doing this twining? I don't get how you're floating this design," or whatever it is. And the kind of social aspect really kind of keeps it sustainable, and what my cousins did was they would come to my mom's house, and the family would get together. We would eat. They would be beading and talking, weaving and chatting, and sharing news, and maybe strategizing, and helping family members who were in need, and whatever-- essentially, these family members just rolled up their sleeves and did whatever they had to, but they were often also doing artwork while they were figuring out life. And so that was a big part of my growing up, and I didn't grow up with a sense that you had to put art aside in order to live well, or to have a community, or any of those things, and so I don't have a strong sense of separation between those things.

Jo Reed: You also self-source your materials as much as possible. Why is that important to your work?

Elizabeth James-Perry: Right. So, I grew up outside a lot, maybe in part because <laughs> my generation, parents used to throw their kids out and lock the door. <laughs> I remember my mother doing that. I don't really see anybody do that with their kids now, at all, which is amazing to me. I don't quite get it.

Jo Reed: That happened to me, too, when I was a kid. It was, "Out, you. Out." I loved it!

<both laugh>

Elizabeth James-Perry: Yeah. Right. But it was great, because you get this year-round just exposure to the outdoors and all the amazingness out there, and you get great exercise. You really develop your lungs, and you play with the other kids, and you figure out life for yourself. Nobody's just doing stuff for you. You're not coddled. And hopefully, you don't get stung or bitten by anything in the process, right? <laughs> That's what our parents were all hoping. Like, "Oh, I hope she survives, but this'll be good for her." And if you think about it, and you hold onto those experiences, you also kind of don't want to give it up. So... <laughs> when I was graduating from college, and I think there was this huge fascination with these eight-hour-plus desk jobs, that never appealed to me at all. I really did not see how anybody did it. I can't sit still that long, wouldn't want to, don't think it's healthy. And so I really loved, in the sciences, you could do field biology and be outdoors all day. You could get up at dawn or earlier. You could be on the water all day. You could travel all over the place, or you needed to travel all over the place. So all of that variety outside really appealed to me, and I loved seeing the birds, and hearing them, and watching the fish, and identifying things, and understanding everything's role, and being part of that. When you source your materials, you have to know where things are on the land, and you have to be really resourceful, because so much of land has been developed. There has to be a certain amount of traveling, monitoring areas, identifying new areas to gather materials, because you don't want to gather out one specific site, or something, and then you can build into it some reciprocity, where you're replanting what you're harvesting. If you're harvesting something and you've got seeds on it, you pull the seeds off, and you leave them in that place. You might decide, if something's really rare, you're not going to go in and pack that. You're going to actually grow it on your property, and then use it in a really sparing way, so you're helping the abundance of that particular species, and maybe raising some awareness, which I think is really important. The species diversity here in New England isn't anything like it was, and it does put pressure on the artist to figure out solutions, whether it's growing what you need or encouraging different organizations to restore certain habitats and environments so that tribal people can have agreements to do a little bit of selective harvesting, and kind of keep that processing knowledge and artistic knowledge alive. There's just a lot of challenges. I enjoy it. I like a challenge anyway, I suppose.

Jo Reed: And you harvest and work with natural dyes…and you revived natural dye techniques. Why led you to do this

Elizabeth James-Perry: I really pursued reviving natural dyes because, as a weaver, I was working with commercial fibers, early in my career, that were commercially dyed. And in one particular project, I started to cough every day, at the end of the day. And... I had some skin irritation, as well, and it really forced me to look at what I was weaving with, and what I was exposing myself to, and what commercial dyes are made of, what happens to the environment if there are spills, and they're released into rivers, and all the fish die. And I'm also living in a part of the state where there is a pretty high cancer rate. So it raises your awareness about the costs. We've got super-speedy, supposedly inexpensive ways in the modern world to produce, produce, produce-- overproduce, in my opinion-- and use and waste, and so thank goodness there is a little bit more of a thoughtful consumptive practice that's emerging, where people hold onto things and really get a lot of use out of them, and then recycle them, instead of just filling landfills with stuff, and exploiting the earth further. I think I had to reckon with what it is to grow things in abundance enough that you can actually make something; that it's not a hobby, and you're not just trying something out, but you have enough dye to rely on for that particular season that's going to carry you through a bunch of projects. You're going to have enough to share, so if a quill worker would like some of your natural-dyed quills, you can produce them and share them. You know, when I had my weaving apprentices here, we'd always take the time to take the yarn, skein it up. I'd show them the dye process, and we'd even do things like enjoy a day at the beach, harvesting some seaweeds, you know, early in the season, when they're nice and fresh, and then bringing them back here, and then just seeing what colors we could get, if they enhanced the take-up of other colors, and things like that, by being additive, et cetera. And so it gives you a deeper appreciation of the lands you're on, when you also know the properties of the plants and how they interact, and what you can make. It's very inspiring, I think.

Jo Reed: Well, you've said the traditional arts are imbued by cultural, ecological knowledge, and this seems to me an example of that.

Elizabeth James-Perry: Mm-hmm, yes.

Jo Reed: Well, one project I really would love to have you discuss is Raven Reshapes Boston: A Native Corn Garden at the MFA. And that’s the Museum of Fine Arts Can you describe that, and what inspired it?

Elizabeth James-Perry: Yes, definitely. And so, Raven Reshapes Boston was a large horseshoe-crab-shaped garden that was mounded up. Our gardening involves mounding as an adaptation. It's sort of like a raised bed that heats up a little bit quicker, and then your plants develop a little bit earlier, so you kind of lengthen the growing season here in New England, which is temperate. The garden was a Three Sisters garden, and it was edged with some indigenous sedge grasses. So, basically, an emphasis on plants that are really important to Native cuisine, and some of them are important for things like weaving basketry and thing like that. They're also really important parts of the environment, in terms of habitat. These sedge grasses are so valuable in so many different ways. And the overall garden was surrounded by tons of quahog shell from my workshop here-- over a ton-- to kind of make the design emerge and connect, really explicitly, the garden to the ocean and ocean life, and emphasize Boston's connection to the coast, which I think doesn't get visually acknowledged much in Boston at all. And so <laughs> its position there, at the MFA, had to do with the MFA reaching out during a time when folks were protesting. The Black Lives Matter movement was full swing. Terrible, tragic things had been happening. People were speaking up, people were marching, and also, people were just trying to educate. And so I think institutions had to reflect on whether they really were being inclusive or not, whether they were engaging with BIPOC artists in the region, et cetera, et cetera. And at the MFA, of course, you have that problematic Dallin statue, which is a white guy's, white artist's, depiction of a sort of composite Native person, indeterminant origin, wearing stuff from several different tribal communities, but not much, on a horse, reaching up to the sky in a manner that might be construed as a bit helpless. So, obviously, not necessarily a beloved image for our Native people in this region. As far as a representation of Native people, it's not accurate to the Northeast Woodlands at all.

Jo Reed: And for people who might not know, that is a statue by Cyrus Dallin called “Appeal to the Great Spirit” which sits in front of the museum’s entrance

Elizabeth James-Perry: It's the first thing you see when you go to the museum, and it's kind of irksome, to say it politely. And so I think my positioning the garden was kind of like a horseshoe crab eating the statue. It was kind of positioned over and moving beyond it. And... you know, the corn was surrounding it. The corn pollinated beautifully. There were corn ears on all the stalks. The corn matured. The corn dried. We harvested the corn. I've got some nice pictures. What I really liked about it was, I would go there sometimes, just unannounced, and just see people walking by, appreciating the garden or experiencing the garden, and see families taking pictures of themselves near the plants, and looking at the plants. And I really wanted something that was reflective of Native culture and values, and environmental values, and an alternative <laughs> to the statue that was more authentic, and that people could freely experience, who were walking, driving by, see from the train, see when they were going to the museum, and that would just make them ask questions. You know, maybe pause and read a sign, maybe talk to Native people, maybe learn more about Native folks in this region.

Jo Reed: Teaching is very important to you, and you do a great deal of mentoring around plant knowledge and sustainability, natural resource protection, and this all interacts with the art that you create and you teach. So, what is it that you want to impart to students?

Elizabeth James-Perry: You know, I think I like to encourage students' creativity and their willingness to find out what's interesting to them, and to explore that, and to find ways to connect with the resources, understand more about the environment that they're in, whether it's local or whether it's knowledge they're taking home to their other tribal communities across the nation. I think that there is beautiful sophistication to our traditional ecological knowledge that goes into practice of arts. And the more of an understanding that you can cultivate about the environment, the more you can help the environment and enrich it, the more there's resources for other artists to practice traditional arts, should they choose, or incorporate it in some way, whether it's obvious or kind of more buried in their art form, in their expressive practice. I want the option to be there. I want the knowledge to be there. I, in no way, <laughs> want to oblige folks in tribal communities to have to practice Native Art-- capital N, capital A-- on a daily basis, because it must be done. I'm not rigid like that, and I would never expect that. And I think, though, if you grow up around it, if you have it in your house, if you hear people talk about it, if you see some people practicing it, it's a choice. I'm not really someone who subscribes to this sort of "vanishing Indian" trope, and "vanishing Indian" knowledge, and "vanishing Indian" arts. I don't really like it. I don't think it's accurate. I don't think it's how life is. I think, if you work to kind of build a pretty strong foundation, people can come in and out. They might be very dedicated to a certain traditional art for a certain phase, but then maybe they start a family. They've got a lot of competing interests, some obligations at home or something, or they're pursuing a career elsewhere. I don't ever-- you know, I don't really believe in penalizing folks for leaving tribal communities to get a decent job or pursue something, because I think you can always stay in touch. You can always come home and visit. You could always pick up a basket and take it with you, that reminds you of home, and I think that it's important to feel comfortable. I think if we impose a lot of rigid guidelines and expectations on what it is to be an artist, and what it is to be a tribal community member in the 21st century, I think, more than anyone else's negative treatment of tribes, I think that would doom us. But I think if we love each other, and take care of each other and the earth, we will always have the choice as to if we want to practice this or that art, or if we want to go to celebrations, or comfortable dancing at powwows and teaching the next generation. We just want to watch, we just want to take a break for a few years, we just want to come back, that's normal and comfortable and natural, and I'm in no way paranoid about this epic loss. <laughs>

<dog collar jingles>

Jo Reed: I hear the dog getting restless so it must be time for us to end—(both laugh)

So, finally, Elizabeth, you're a 2023 National Heritage Fellow. What does this award mean to you, and mean for the work that you're doing?

Elizabeth James-Perry: The award was an amazing honor, and it was pretty humbling, and it was also just super encouraging. It was encouraging for me, personally, but it was encouraging. I think it was encouraging because, in the Northeast, I feel, actually, like a lot of our arts haven't gotten a lot of attention. In spite of the practice of fiber arts, in spite of wampum artists, in spite of folks who've really delved into archery traditions and things like that, I really still feel like there's just very low visibility. As you drive around New England, you'd never know we were here, in a lot of ways, unless you know tribal people, if you're a tribal person, perhaps you know. It's hard to articulate the extent of it, but I really think-- I believe in the ripple effect, and I do think that, in recognizing one person, I think, more explicitly, you're recognizing the arts from a particular region, and giving them more visibility, and raising their profile. And it's just another way of, I think, making those arts sustainable. I think it feeds into the whole... encouraging arts at all levels. I think encouraging... not everybody, necessarily, to pursue it in a really strict way, and nothing else, but seeing the value. And so, whether you're practicing the art, or paying attention to the art, or perhaps writing about it, or reading about it avidly in your spare time, or having a collection in your house that you can really appreciate, and all of your visitors get to appreciate, as well, I think there is lots of ways to be involved and be supportive of art and culture, and lots of ways to be supportive of other arts. Yeah, I-- there's so much to be said. Oh, my gosh. <laughs>

Jo Reed: Well, let me just add my congratulations.

Elizabeth James-Perry: Thank you.

Jo Reed: And it's so well deserved. Your work is just beautiful and profound in many, many ways, on every level, so thank you.

Elizabeth James-Perry: Thank you.

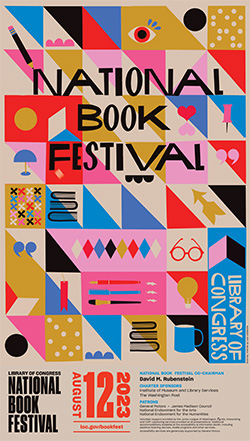

Jo Reed: That was Wampum & Fiber Artist and 2023 National Heritage Fellow Elizabeth James-Perry. You can find more about her and see examples of her brilliant work at arts.gov or on her website Elizabethjamesperry.com. We’ll have links to both in our show notes. And mark your calendars for September 29 when the 2023 National Heritage Fellows will receive their awards at the Library of Congress. Check out arts.gov for details as the date approaches.

You've been listening to Art Works produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. We’d love to know your thoughts—email us at artworkspod@arts.gov. And follow us wherever you get your podcasts and leave us a rating on Apple, it helps other people who love the arts to find us. For the National Endowment for the Arts, I’m Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.

###