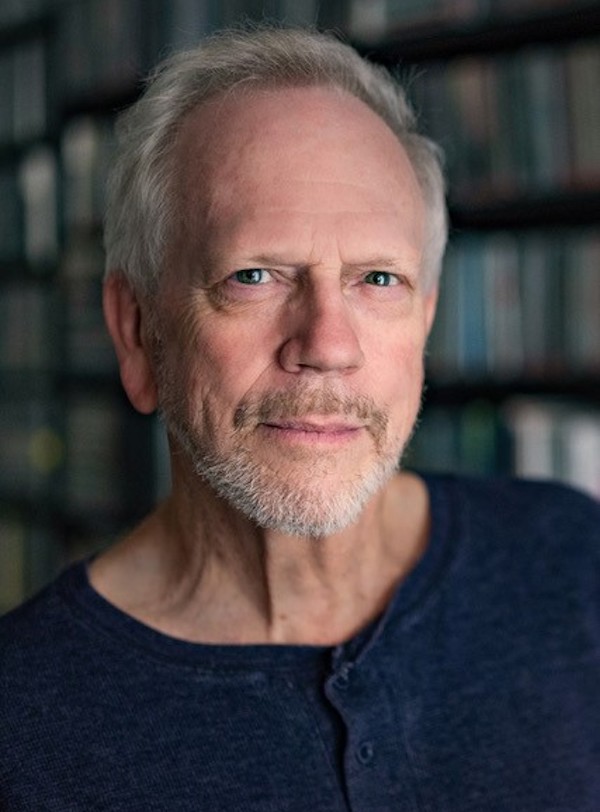

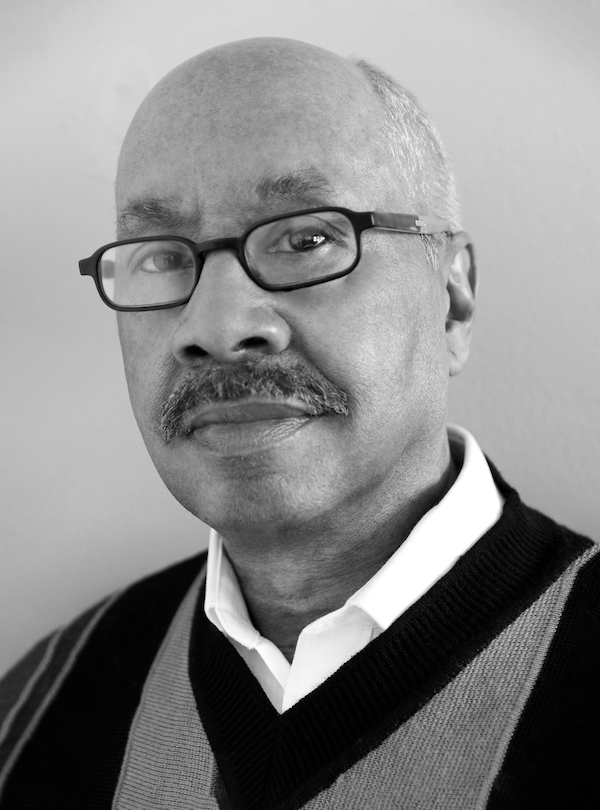

Nick Spitzer

Photo by Rusty Costanza, courtesy of Tulane University

Photo by Rusty Costanza, courtesy of Tulane University

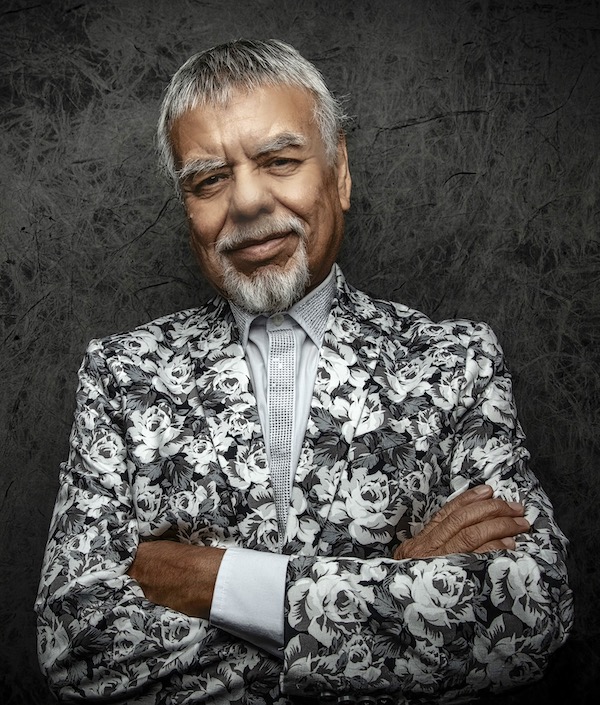

Photo by David Bazemore

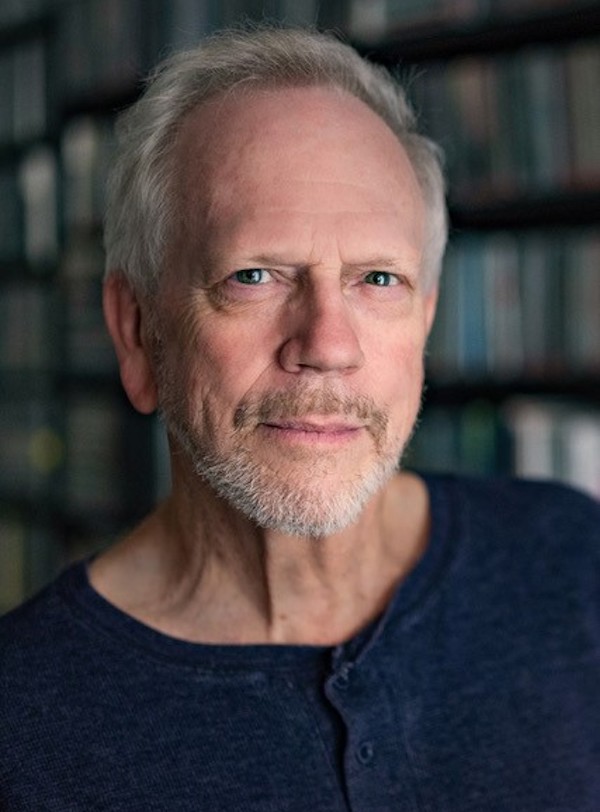

Photo © Jack Parsons. Courtesy Luis Tapia

Photo courtesy of Elizabeth James-Perry

Photo by Lynn Martin Graton

Photo credit Mark Del Castillo

Photo by Rustin Gudim

Photo courtesy of the artist

Photo by Stuart Isett

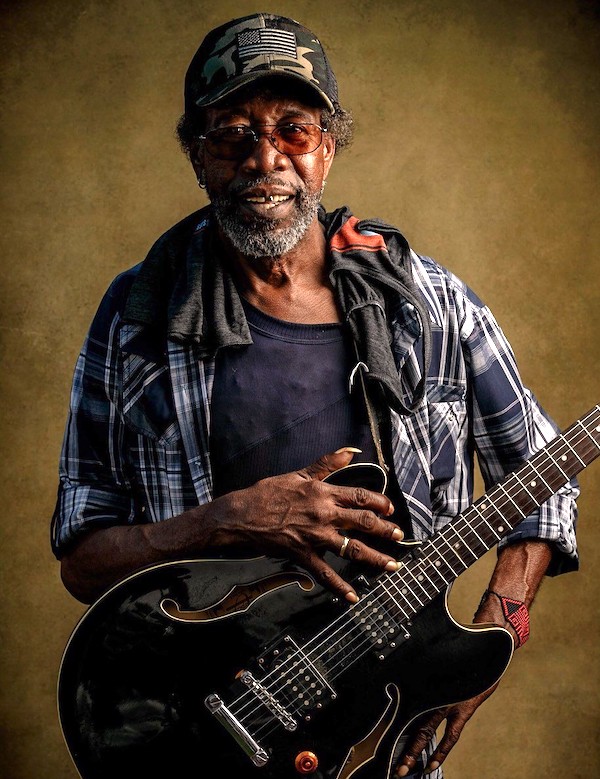

Louis Hayes: The Jazz Messengers was disbanding, and Art Blakey was keeping the name Jazz Messengers, and Horace Silver, the pianist, was starting his own band. So Doug Wattles and Donald Byrd said to Horace Silver to get me from Detroit to be in the group. So Horace Silver called me in August of 1956, and that just that fixed me right up. My dreams were coming true. And so I came to New York to join Horace Silver at that time. And that period with Horace Silver was just magnificent. He wrote so much music, and we got along at such a high level. So that's how I started my career at this place that I always wanted to be: New York.