Valerie Miles

Photo by Alan Howard

Photo by Andrea Sollenberger Photography

Photo by Isabel Darcy-Johnston

Photo by Tahel Frosh

Photo by Chase Reynolds

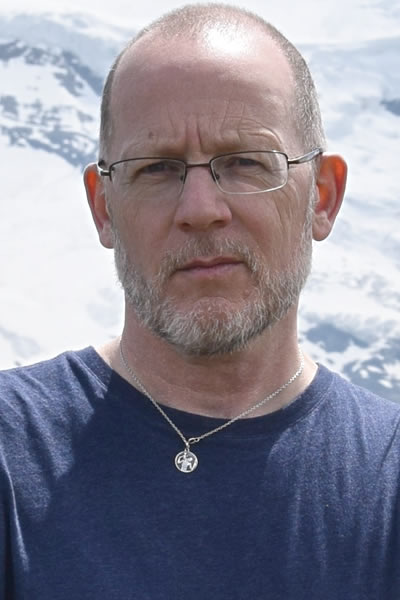

Photo courtesy of Brian Henry

Photo by David Anderson

Cedric Burnside: I was always around the music. It was in my blood. I feel like I was born with this music in me, but I was always around it from a little kid and I used to watch my dad, Calvin Jackson, and my uncles, Daniel Burnside and Joseph Burnside, and my big daddy, of course, R.L. I used to watch them play every other weekend and I knew it was just something that I wanted to do for the rest of my life, even at a young age, six, seven years old. I watched my dad on the drums and I just watched him in amazement. I watched my big daddy and he was signing and he was playing and his voice was like something that was out of this world and I knew it was something that I wanted to do for the rest of my life and I knew that at a young age.