Phenomenal Women: Exhibiting Greatness

Grant Spotlight: StageOne Family Theatre's Production of Lawbreakers!

Megan Massie, Ebony Jordan, and A.J. Baldwin portray Alice Paul, Ida B. Wells, and Angelina Weld Grimké in a pivotal moment where the inequality in the women’s suffrage movement comes to a head. Photo courtesy of StageOne Family Theatre

Rhiannon Giddens

Music Credits: “Goin' Down The Road Feeling Bad” traditional, performed by Carolina Chocolate Drops & Joe Thompson from the cd, Carolina Chocolate Drops & Joe Thompson.

“The Angels Laid Him Away” written and performed by Rhiannon Giddens from the cd, Freedom Highway.

“Trouble in your Mind,” traditional, performed by Carolina Chocolate Drops from the cd, Genuine Negro Jig.

“NY” composed and performed by Kosta T from the cd Soul Sand, used courtesy of the Free Music Archive.

Rhiannon Giddens: I started dancing at this local concerts and squares, and the bands were old-time bands, and I was like what is this, like I heard bluegrass but the old-time banjo is totally something different and it's much more connected for me to like the African sounds, the African diasporic sounds that would have come from the original banjo which is an African-American-Caribbean invention, and I didn't know it at the time but I was just so connected to that beat and that sound and then I just wanted to play it.

Jo Reed: That is singer/songwriter/multi-instrumentalist and the artistic director of Silkroad, Rhiannon Giddens, and this is Art Works, the weekly podcast from the National Endowment for the Arts, I’m Josephine Reed. As we celebrate Women’s History Month this March, the National Endowment for the Arts is shining a light on some phenomenal women—past and present-- through the agency’s blog, podcast, and social media channels. We’re celebrating women who, to borrow from Maya Angelou’s famous poem “Phenomenal Woman” have “fire in their eyes and joy in their feet.” and which is kind of a perfect description of Rhiannon Giddens.

A classically-trained singer, MacArthur Fellow, banjo and fiddle-player and composer, Rhiannon excavates the past to bring forgotten stories and music forward. A daughter of North Carolina, her music is a reflection of and has roots in her multi-racial background.

Rhiannon is co-founder of the Grammy-winning Carolina Chocolate Drops, which insisted reclaiming a central and historically-accurate place for black musicians in old-time music. Rhiannon then went on to create solo albums of haunting beauty and power that mined African-Americans past and present. Always searching, Her most recent album with musician Francisco Turrisi ranges from bluegrass to gospel to traditional Italian songs. She is an artist determined to be of service and put her wide knowledge of different musical traditions to good use.

Given that Silk road was begun by YoYo Ma in 2000 as both a touring ensemble of world-class musicians from all over the globe, and a social impact organization working to make a positive impact across borders through the arts, it was perhaps not so surprising that in July, Rhiannon Giddens was named to be its artistic director. I spoke with Rhiannon Giddens recently and asked her what attracted her to this new role with Silkroad.

Rhiannon Giddens: A lot of things I think. Firstly, I am, I don't know, I'm a new thing kind of person. I'm always interested in how to do things that I don't know how to do, and if I feel like they are close enough to what I already do I will try it, and if I think it makes sense for me and if I can learn and then, of course, most importantly if I can offer something up for that role. I don't want to do something just for the sake of doing it because that's not really respectful. But this came at a time where I had been performing a lot and traveling a lot and was a little bit burned out, a little bit just because of the intense nature of the work that I do and the music that I sing and the historical connection and all of that, and also the other thing that kind of made me think twice about it rather than just kind of going, oh, no way, was my partnership with Francesco Turrisi who we had been, you know we'd made a record together and we'd been doing things, and he has kind of connected my music to the rest of the world for me. So I had been doing such a deep dive in American history and American cultural music, and then he comes from the Mediterranean and thinking about you know his questions of why don't we talk more about how like North Africa and the Middle East really influence so much of the European art, and there's all these reasons, and so I was just kind of realizing there's such a larger picture, which I always knew but it really kind of brought it home to me, you can't actually finish this story without looking at what came before and what was happening in the rest of the world. So through I've been learning about lots of instruments and types of music that I would have never known anything about. So it gave me a little bit of confidence, like, look, I have so much to learn about the group, about all the instruments, about the music. I have a lot to learn, but I think that's a strength to know when you have a lot to learn and what you have to offer and when you need to learn more, and they always go hand in hand, you know? But knowing him and having experimented and learned a lot about like maqams and frame drums and things like this that were outside of my realm kind of gave me a little bit of confidence to go, okay, well, at least I have a little bit more of a basis to take this job, like I think if the offer had come like two or three years prior I would have had to say no because I don't feel, I wouldn't have, at that point, had the right perspective. But I feel like at this point I have just enough knowledge to know what I need to know and to be open to learning. But I also have a very particular point of view which can be really useful for where the organization is after 20 years of being in existence. That's a point usually, you know whether in marriages or in organizations you reach a point where you've been a certain thing for a while and then you have to make a decision, do we continue doing this certain thing, do we go our separate ways, do we do a different thing but together. It's a natural thing for any kind of long-standing organization, especially a group of artists. So just all of the sort of different pieces of it seemed to say this is a good idea, and I have the people around me who can help me with the stuff that I don't know. Because I don't think everybody needs to know everything, I think you have to have the group around you that can kind of fill in the blanks and so that you're each kind of doing what you're best at, and I thought I could bring a perspective. That's a long answer to a short question.

Jo Reed: Your own musical background is wide and its deep, and did you grow up in a musical family? It almost seems like it was fed to you with mother's milk.

Rhiannon Giddens: Well, in some ways yes and in some ways no, so I'm an interesting mix I think. I'm fortunate because I did sing a lot with my family, my dad in particular, like we just sang all the time. We would just sing wordless melodies, and he was a classically trained singer that ends up going into a different industry for various reasons that I won't get into here. But he was just an amazing singer and guitar player, and so I was always around that and I just was always a singer, like family lore, I'm like singing as soon as I can draw breath basically and never stopped and annoyed my mother to no end because I wouldn't shut up. But I was in a very nurturing environment for my good fortune because like they didn't, my parents didn't push me. My dad didn't see that I was musical and then go, "Oh, let me get her into all of this stuff and teach her how," you know he was just like let me just sing with her and like let's make music, and so that's kind of been at the core of everything, and I didn't have, any formal training I have was in a choir which was great. But then not really knowing, you know not really engaging with it in a really formal sense until college, and so like my sister and I would want to go, you sing at the talent searches, and my mom would be like, no. She just was like there's no need for that right now, and I just think that was the best thing ever because it meant when I got into music I got into it for the love of it, not because I saw it could give me applause or it could give approbation, and so I've always been into it I think for the right reasons for me, and I can't speak for anybody else, but it works for me and the idea of the mission that I've been kind of on for a long time really feeds into that because I wasn't happy until I found that mission, which is why I left opera because I just couldn't reconcile like that I needed a connection to what I was doing deeper than just singing these stories, which is amazing, I love opera. I mean, I loved it, I love singing, I miss it to this day. In some ways that was where I was the happiest in terms of not having to think about anything but just I'm singing this thing, you know singing the most beautiful notes I could possibly sing and emotionally and blah, blah, blah, and there's not much about my life now that is like that. So there's so much head stuff going on, but I think that that's kind of informed everything. So I didn't have specific like cultural, I mean I had cultural touchstones because I was born and raised in the South, but I've brought that whole idea to everything, whether it's Celtic music, Scots Gaelic or old-time music or opera when I came back to it, writing it now and all that kind of stuff, I think, you know and again that sits really squarely with what Silkroad is trying to do, so it's really using the beauty of art and the emotional ties that art creates with a listener or a watcher, it could be dance, and then using that as a way to better the world, and so even from that point of view it was a great fit, even if you don't think of anything else, like I was like, oh, wow, this is a way that I can do this thing that I've been obsessed with, i.e., like doing that exact thing but on a bigger platform than I have on my own, so it's a I'm joining the family, which is lovely, it's a really wonderful feeling.

Jo Reed: Okay, you studied classical voice at Oberlin and then when you came back you stepped out of that world, that doesn't surprise me, but that you hadn't picked up a banjo until then, that surprised me. First, what drew you to the banjo? And, my God, you became very proficient very quickly.

Rhiannon Giddens: Well, I like to say I don't play many notes on the banjo, but the ones that I play I really know what I'm doing with them. I'm not Chris Thile on the banjo, far from it, like I know what I know and I stick to it, but what I know I play it a lot, and I think that that's an interesting approach and one that is not, it's not often honored in the classical world, it's like you've got to do everything with your instrument, and that is one way of making art in a very high fashion, but you know what, you can also be a folk artist that does this thing but like amazingly well and it has this connection to it that sometimes the other doesn't. It's just like it's a give and take and it's a tradeoff sometimes. But that art is not held up to the same kind of loft. It's like I think art music has been taken too high given where a lot of classical music comes from. A lot of classical music is very influenced by vernacular. There used to be much more of an exchange there, and I think that it has just become such a classist thing which is one of the reasons, this is one of the things that I didn't like about opera. I was like why doesn't everybody have access to this, I love these melodies, I love this music, I love these tunes, like why is it so inaccessible to people, why is this so cut off, and anyway so when I didn't play anything, I play a few guitar chords but that was it, and I started dancing, but when I got home I just kind of burned out of classical, I just needed a break, and I got home to North Carolina and I started dancing at this local concerts and squares, and the bands were old-time bands, and I was like what is this, like I heard bluegrass but the old-time banjo is totally something different and it's much more connected for me to like the African sounds, the African diasporic sounds that would have come from the original banjo which is an African-American-Caribbean invention, and I didn't know it at the time but I was just so connected to that beat and that sound and then I just wanted to play it. So and I didn't play fiddle either, so I picked up of them kind of within a year of each other and just was extremely frustrated, it sounded like crap for a long time. But I was very lucky because I think, and this is an experience that I wish, that I think we all should have at least once every 10 years is that we should learn to do something completely that we don't know how to do and try to get good at it, because it reminds us of what it feels like to suck. Because you kind of get good at something and then that's what you do, right, and we kind of stick to what we are good at because nobody wants to suck because it's not fun, I wasn't looking to be a violinist or a banjoist, I used the music to get to what I wanted which was to play dance music, or to play with Joe Thompson eventually, when I met him, the last African-American practitioner of the old style black fiddle and banjo music, and so you just use the notes that you need in that kind of music. When you're playing dance music you don't try to learn all the notes, and also it's an apprenticeship so you're doing it all by ear, and I'm not recording stuff, I'm just learning in the moment. I mean, recording is important but I almost never listened to them when I made them, it was just really, we just sat and played over and over again and then me and the Chocolate Drops would just play over and over again, and then we would play for kids who tell, you know they immediately tell you if it sucks. We would play for dancers, same thing, they want you to support them, and so that was the beginning of my instrumental career and it has been the best thing ever because it's that sense of service that I think, you know I was just talking to some folks from a conservatory and it's just like the idea of artists being of service I think is really lost, it's not a part of our conservatory training, and an organization like Silkroad, that's exactly what we, I say we now, are doing, is being of service with our music. I'm so into this realizing, you know kind of looking back on my life as one of service as a musician and realizing how much that brought me as a musician. As much as I love standing there singing that high note with all the costume and just the amazing sheer awesomeness of it, doing something with my music as well brings an equally transcendent moment, you know what I mean, feeling like it is serving brings its own kind of joy, and I just think that that is, we need more of that.

Jo Reed: I'm glad you brought up Joe Thompson because he is a National Heritage Fellow.

Rhiannon Giddens: Yes.

Jo Reed: I would love to have talk about your interactions with him because he is such an important figure in American music.

Rhiannon Giddens: We were so lucky, we didn't know then how lucky we were. I think we know now, like me and Dom Flemings and Justin Robinson, the original Carolina Chocolate Drops, we started going down to meet Joe, Joe was 86 at that time, and he'd had a stroke but he'd kind of recovered enough to be able to play, which was amazing, and the white community around Mebane, which is where he lived, you know the white old-time community, had been really active in keeping him playing because he wouldn't play by himself, and this is a really integral part of the kind of music that he came from, he wouldn't play without a banjo player, which is one of the reasons why I ended up playing banjo in the band because I was the only one who could, so I said, well, I'm sticking with the banjo and filling the slot that needs to be filled, and I'm really grateful for that because I learned everything that I know. Well, not everything, of course, we all have multiple teachers, but the core of how I played banjo comes from playing with Joe Thompson, and he was an amazing, gentle, you know I think he was aware of the importance of his music but not enough to be too stressed about it. I don't know, I just think he knew his job was to teach and so he taught anybody who wanted to come by, and by teaching he played with them, and he was a really open person, and we got him for a handful of years which was really amazing, like a couple of those years were really intensely learning from him and playing with him and playing with him in public, and then when John Jeremiah Sullivan's article came out connecting Joe Thompson to Frank Johnson who was a black string band musician, he was a fiddler who had bought himself out of slavery with his fiddle, and bought his family out of slavery, and formed this string band which was famous all over the South, so famous that they actually started calling the music he played Frank Johnson music, like he was hugely influential, right, and so when Sullivan connected him to Joe Thompson it was like, I can't even explain how big of a deal that was to me. In African-American history it's so difficult to get names and connections because of the nature of enslavement, because of the nature of being discarded, and most people, it's very hard for them to trace back over the ocean, you know a lot of people have a hard time getting specific names for their family tree. That didn't matter so much to me, this did. I actually have a musical lineage that has a name at the end of it, which was really incredible, and it was like I was, you know we realized, okay, we were like this is really great, we were able to do this with a living member of the African-American community, this music which was almost dead in our culture, and then however many years later it was like another wave of, oh, my gosh, like we almost missed that. He was 86, you know we almost missed that, and it almost kind of freaks you out because you're just like, oh, because it's such an important thing, and so it really does inform so much of how I look at music and how I look at the world really, is having that experience.

Jo Reed: Well, some of the songs you sing, you unearth, and, in fact, I know you've worked with Sheila Kay Adams who is another National Heritage Fellow, and then others you write yourself, and you've been inspired to song by narratives of enslaved people, bringing that past into the present, and it reminds me of Tracy K. Smith and her collection of poetry "Wade in the Water," one of those longer poems, she's just using excerpts from letters of formerly enslaved people, and I see you two doing very similar work in that regard. Talk about the importance of that, of filling that story out.

Rhiannon Giddens: I just, I think the more that we can listen to the voices, I mean, it's important to listen to the analytics and the analyzers and the people who contextualize things, I mean, they have been my saviors. I've read so many incredible books by so many amazing academics who've done all that leg work that I don't have to do, and that's important to set the scene, but when it comes to the emotional heart of it, it has to be from the voices. There are a lot of different ways of going at it. There is looking at the voices of enslaved people, which always has to be taken with a really big grain of salt because of the different levels that the meaning has to fight through because a lot of the people in the WPA, the narratives project, were very old when they were talked to. They were talking to white people, white people were sometimes writing them in dialect even if they weren't talking in dialects, white people were asking leading questions, and it's not to say that that work wasn't good work, it was, but it was work of the time. So we have to remember that there's still a code that's happening in a lot of these narratives, so I always try to keep that in mind, and the other thing is that it's not always just their voices. For me, I also get a lot from reading letters written by enslavers, written one enslaver to another, don't forget, here's some tips to keep your poor whites angry at the black people and vice versa, don't forget, you've got to keep the crackers and the, you know what I mean, like they were just really super clear, like they were so clear why can't we be clear, and that's kind of the line I take, and there's also the voices of people who write runaway ads, people who write slave advertisements, those are also important voices, they're tough voices because they're voices of the oppressor, but they still can uncover things that have an emotional veracity to them. So for me the primary sources, even if within a book, their voices come clear. Now, what it means and the layers and the coding and all that stuff, that's a whole other ball of wax, and that's where the contextualism really does come in handy because the more that you read about the time around when these people were living I think the more that you can intuit some of the things that are coming from their words, or understand why they would say this or that, at least as much as you can coming as a 20th-century born person, and living in comparative luxury to any of these people. So that in and of itself is a barrier that I'm very open about. It's like I can only tell the story as I can feel it from these words, but it's imperative to me to go as far as I can to those people, which we have words, we have sometimes oral traditions, oral histories that were written down, those are amazing too, and so that's just kind of how I look at it.

Jo Reed: Yeah, well, it's teaching history through song, it's singing history, and I don't mean it'd didactic at all. But there is so much that music is capable of because it opens the heart as well as the head, and you're not being talked at but at the same time you're forced to recognize the partiality of history as it has been taught.

Rhiannon Giddens: Yeah, and I think that there is, it's a team effort. I always kind of look at myself as the performing arts arm of the historian society because it takes so much to get this knowledge to light. But like a musician has an ability sometimes to take a three-minute song and that person who is never going to read that book can get the gist of something really important from that book after listening to that three-minute song, and I think that's where I come in, and it has felt like a service, it has felt like a call to action, like I just feel like it is a calling for me. These songs, I don't know where they'll be in 50 years, I don't really care. I feel like if they're doing their job right now that's all that matters, and if I'm representing, because I listen to voices or read voices but I also try to represent the voices in a way that feels right, so to try to get out of the way as much as I can to allow the song to be what the song needs to be.

Jo Reed: You've written an opera called "Omar," which also has its historical traces. Tell me the story and how it came to you.

Rhiannon Giddens: Well, the amazing folks at the Spoleto Festival in South Carolina, Spoleto USA, they decided they had never commissioned an opera before and they decided they wanted to tell the story of Omar Ibn Said who was a Senegalese Koranic scholar who was stolen and sold into slavery and ended up first in Charleston and then ran away from his enslaver in Charleston and ended up in North Carolina, and he ended up a slave for 50 years and he wrote his autobiography in Arabic, which is an amazing feat considering that as soon as he stepped foot in America like he no longer could speak any of the languages that he spoke with people. He couldn't speak Arabic, which wouldn't have been his first language, you have to read the Koran in Arabic, right, so he learned it, but he would have been very proficient in it. You know couldn't speak any of his native languages, and to be able to retain, the Arabic and the Koranic verses, like he could quote huge swaths until he died, just shows an amazing force of will, and he's just a really incredible person, and what he said with his writings and how he walked that line, living in a Christian, not only enslaved but also enslaved by Christians and so how did he keep his faith and all of these questions were very interesting to me. I'd never heard the story, I mean, despite being born and raised in North Carolina I'd never heard of Omar, which made me mad all over again. Every time this happens I'm just like, what, why is somebody else telling me my own history, this is terrible, and so I wrote the libretto and I partnered with Michael Ables who is an incredible composer, and he writes film scores, he does classical composition, he's just an all around amazing guy, and I said would you write this with me because I can come up with the thematic material but I don't know the orchestra, I don't know dots, it's going to take 14 years, and I just loved what he did with the soundtrack to "Get Out" which is that amazing Jordan Peele movie.

Jo Reed: Yes.

Rhiannon Giddens: Right? And I was just like, oh, my God.

Jo Reed: That was some scary music.

Rhiannon Giddens: Yeah, he's incredible, and what he has done with what I send him is just stunning. Basically the whole orchestra is a banjo, like I've written most of the, a lot of the music on the banjo, and it's a mixture of folkloric kind of stuff and classical, you know because I was classically trained so I go into that when the spirit hits, but it's just a real, the patchwork of who I am, and he has really made it come to life, and he has added his own pieces to it, but he's made it come to life and in just a stunning way, and I think it's a really good example of fusion, of classical folk fusion, I think it's a real example. I think there's been attempts, and I'm sure there are real examples that I just haven't heard, but for me it feels like this is really two worlds meeting at their peak and then combining to, you know this is not an arrangement of a folk song, it really is something new, it's a real coming together, and I just have never heard anything like it, so I'm excited. I've done as much as I can as a composer, I'm not a writer, I'm not writing a history of enslaved Koranic scholars. So I kind of had to draw a line and go, okay, I can do as much as I can but ultimately I have to write a good opera that's telling the story of my Omar, this is not the Omar because he's gone, all we have is his words that he left behind, and, again, multiple layers, who is he talking to, who does he, you know who knows who is reading his story. So even within that he's very strong in what he's saying so I would love to like know what he would have said without having those layers laid upon his work, but, yeah, it has been a real privilege to work on that.

Jo Reed: I'm curious about how you're going to take some of your life's work which has been a musical historical excavation and bring it to the Silkroad.

Rhiannon Giddens: Well, and, again, this is where Francesco comes back in, the idea of American music as immigrant music, that's really where it begins because the work that I've done it's just over and over and over and over again, it's like this comes from here, this comes from here, there's nothing in America other than indigenous music, which is a whole story of its own, how it has been erased and overlooked and forgotten, I mean, indigenous people are still around, agriculture is still happening. Other than that everything has been brought, right, so whether by force or by choice, or by forced choice depending on where you're coming from. So the fact that anybody could look at American music, because this continued up until the current day, like it's not like this happened in 1705 then that was it, it just kind of went from there and has been American music ever since then, that's just not true. There's been wave after wave after wave, and every wave makes this huge change, and at the core of all of it is this sort of black, white working class cultural exchange that has generated so much of what's going on. So there's all this going on and I'm like so all we need to do really is to connect that to what Silkroad has been doing. For me it's not hard because you have people of all those populations that are represented by what Silkroad has been doing in America, like so how has it affected American music, how could we put American music back within the context of global music, and so I just think one of the projects that came to my mind immediately is talking about the railroad, particularly because you have an interesting combination of a lot of Chinese laborers, which, of course, Chinese music has been a huge part of Silkroad music and history, and then you have African-American laborers, you have Irish laborers, you have other European immigrant populations, and you have all of this stuff going on to build a capitalist kind of connector, right? So this railroad is not for people to get from point A to point B, it's for goods to get from point A to point B. So it's like the best and the worst of America, there's a lot of the worst of America in the railroads when you consider how the workers were treated, which was awful, how you consider the land that they went through and stole, like Native lands, to connect the East to the West, what runaway economic progress does, who does it benefit, who does it take from, who dies to make it happen, these are the things that we are going to explore with that project. It's like basically bringing Silkroad into America, it's like we have a lot of the same things that were going on along that route and that's been explored in certain ways for 20 years and it's beautiful, and we'll continue to explore that, but I think it's important to, a lot of the people in Silkroad ensemble live in the States, I just think it's a really I think great opportunity to expose the world within America by using that historical event and the people who are involved in that as a jumping off point for creating art, for creating discussion, for that kind of thing. So that's pretty much the first idea that I have had that we're now building into a multi-year kind of really big project because there's a lot that can be done with it that's coming from my specific perspective to Silkroad.

Jo Reed: That’s wonderful, and the impact of COVID on planning…

Rhiannon Giddens: It's interesting actually, it's been difficult but it's also been, you know Silkroad was in kind of a bit of flux, like I said, any organization that's been around for a long time, and then also there's a transition of the original founder, so Yo-Yo Ma had stepped down, and there's this idea of recommitting to what Silkroad already is, but then also going, well, what is Silkroad right now, what's Silkroad of 2020. We know what Silkroad of 2000 was; 2005, 2010 maybe we weren't sure; 2015, I don't know. But in 2020 it's like everything has stopped, this transition has happened, Yo-Yo stepped down, there was an interim Artistic Director model that was dissolved, and then I stepped in as the sole Artistic Director, and so this is the moment where there's a reckoning that can happen within any organization, you go, okay, so who are we now, what do we want to say, how is it structured, everything is stopped anyway so let's take this opportunity to shore up the things we want to shore up, to change whatever, and really kind of be the organization that we want to be for now and make the work that we do count even more, more efficient, all of that kind of stuff that every organization should do, and so we've had an opportunity to do that in a way that wasn't actually as painful as it would have been if we'd had to do that while also keeping everything going, and so everybody is in their houses, we're all available for Zooms, and we're able to, so for me it's kind of like it's a little sad because I haven't met 95 percent of the people that I talk to in person yet, so I'm meeting everybody over a screen, which is tough, but on the other hand it has given us an opportunity to really investigate these things and to kind of come together in a way that's been really beautiful. I just think we're in a really good spot to start making stuff as Silkroad 2021.

Jo Reed: And I think that's a great place to leave it, Rhiannon. Thank you so much for giving me your time, I really appreciate it.

Rhiannon Giddens: You're welcome

Jo Reed: That was singer/songwriter/multi-instrumentalist and the artistic director of Silkroad, Rhiannon Giddens. You can learn more about Silkroad at silkroad.org. and keep up with the phenomenal women we’re highlighting this month at arts.gov. Just follow us on twitter @neaarts. This has been Art Works produced by the National Endowment for the Arts. I’m Josephine Reed. Stay safe and thanks for listening.

Taking Note: The Social Determinants of Arts Engagement

Phenomenal Woman: Get to Know National Endowment for the Arts General Counsel India Pinkney

India Pinkney. Photo by Carrie Holbo Photography.

Sneak Peek: Rhiannon Giddens Podcast

Jo Reed: You mentioned Joe Thompson—he’s a National Heritage Fellow which is the award the arts endowment gives to folk and traditional artists. I would love to have talk about your interactions with him because he’s such an important figure in American music

Rhiannon Giddens: We were so lucky, we didn't know then how lucky we were. I think we know now, like me and Dom Flemings and Justin Robinson, the original Carolina Chocolate Drops, we started going down to meet Joe, Joe was 86 at that time, and he'd had a stroke but he'd kind of recovered enough to be able to play, which was amazing, and the white community around Mebane, which is where he lived, you know the white old-time community, had been really active in keeping him playing because he wouldn't play by himself, and this is a really integral part of the kind of music that he came from, he wouldn't play without a banjo player, which is one of the reasons why I ended up playing banjo in the band because I was the only one who could, so I said, well, I'm sticking with the banjo and filling the slot that needs to be filled, and I'm really grateful for that because the core of how I played banjo comes from playing with Joe Thompson, and he was an amazing, gentle, you know I think he was aware of the importance of his music but not enough to be too stressed about it. I don't know, I just think he knew his job was to teach and so he taught anybody who wanted to come by, and by teaching he played with them, and he was a really open person, and we got him for a handful of years which was really amazing, like a couple of those years were really intensely learning from him and playing with him and playing with him in public, and then when John Jeremiah Sullivan's article came out connecting Joe Thompson to Frank Johnson who had been completely forgotten but who was a black string band musician, he was a fiddler who had bought himself out of slavery with his fiddle, and bought his family out of slavery, and formed this string band which was famous all over the South, so famous that they actually started calling the music he played Frank Johnson music, like he was hugely influential, right, and so when Sullivan connected him to Joe Thompson. I can't even explain how big of a deal that was to me. In African-American history it's so difficult to get names and connections because of the nature of enslavement, because of the nature of being discarded, and most people, it's very hard for them to trace back over the ocean, you know a lot of people have a hard time getting specific names for their family tree. That didn't matter so much to me, this did. I actually have a musical lineage that has a name at the end of it. And we realized we were able to do this with a living member of the African-American community, this music which was almost dead in our culture. It's such an important thing, and so it really does inform so much of how I look at music and how I look at the world really, is having that experience.

Phenomenal Woman May Sarton Dares Us to Be Ourselves

Keep Us Strong: Poems in Celebration of Black History Month

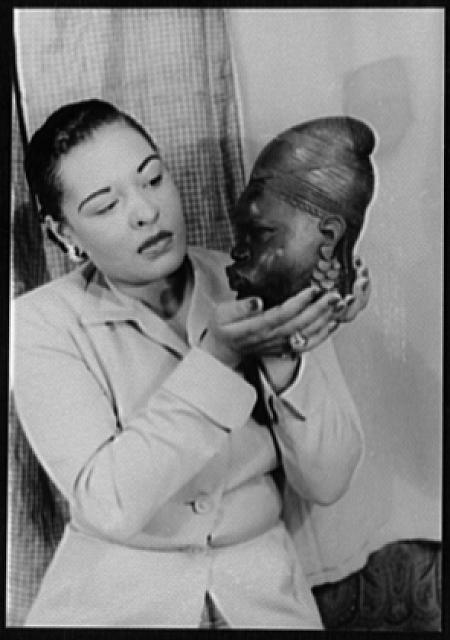

Portrait of Billie Holiday, March 1949 by Carl Van Vechten. From Library of Congress Carl Van Vechten portrait collection

Henry Threadgill

Music Credits:

"Melin" from the album When Was That? Composed by Henry Threadgill, performed by The Henry Threadgill Sextet.

Zooid. "In for a Penny, In for a Pound," from the album In for a Penny, In for a Pound. Composed by Henry Threadgill and performed by Zooid.

“Untitled Tango” from the album Air Song, Composed by Henry Threadgill and performed by Air.

"NY" from the album Soul Sand. Free Music Archive, 2015.

You’re listening to an excerpt from “In for a Penny, In for a Pound” performed by Zooid and composed by 2021 NEA Jazz Master, Henry Threadgill and this is Artworks, the weekly podcast from the National Endowment for the Arts. I’m Josephine Reed. Henry Threadgill is a groundbreaking composer, musician and band leader on the leading edge of avant-garde jazz since the 1960s. Born on the South Side of Chicago, he came up in a musically varied world where the sounds of gospel, blues and marching bands all blended comfortably together. A multi-instrumentalist who focused on the alto sax, clarinet and later the flute, Threadgill was 19 when he met Muhal Richard Abrams and he played in Abrams’ experimental band which evolved into the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians or AACM, a collective that encouraged musicians to compose and play their own music. Henry Threadgill formed the group Air with Fred Hopkins and Steve McCall releasing albums that explored the edges of improvisation. He then went on to work with ensembles of varying sizes composing new work and experimenting with instrumentation including instruments like cello, tuba and multiple guitars to play his complicated compositions. His groups include but are not limited to the Henry Threadgill Sextett, Very Very Circus, Make a Move and Zooid. Threadgill is a sought after composer whose work is premiered nationally and internationally at venues like the Brooklyn Academy of Music, Carnegie Hall and the Venice Biennale. He received an NEA Jazz Composition Fellowship in 1974 and went onto to receive any number of awards including a Guggenheim Fellowship and Doris Duke Artist Award. In 2016, he became only the third jazz artist to receive the Pulitzer Prize for music for his album “In for a Penny, In for a Pound” and now Henry Threadgill has been named a 2021 NEA Jazz master. I have the opportunity recently to speak with Henry via Zoom and I began our conversation by asking him about his earliest musical influences.

Henry Threadgill: Well, there was no television. Radio had all the music that you were going to hear inside the house wherever you lived. The only music that you heard outside was if you went to a church or you were standing at a parade. I can remember the music from the time I was three years old listening to the radio and that music was classical European music of Serbian music because the largest Serbian community is in Chicago and it was Polish music because also that’s the largest Polish community and then you had rhythm and blues and blues and jazz and gospel music on the radio. So that was something that I would listen to on a daily basis. This is before I started grammar school and then I would hear music at my two different grandmother’s churches. One church was a Baptist church and this was a very sophisticated choir that read music and sang a lot of anthems and it was the church that my father’s mother belonged to. My other grandmother, my mother’s mother, that’s where the music I loved the most. This was a Church of God and Christ. They had a singing minister there named Singing Sammy Lewis. He was a minister and he sang and there was something about singing ministers. There was something about them, their ability to deliver words in song was exceptional. So I was influenced and captive by all these things when I was three and four years old.

And when did you begin to play an instrument yourself and what was it?

Henry Threadgill: The first instrument I played was the piano. I started playing the piano when I was about three and a half years old. What happened was this, the music that was famous at that time was Boogie-woogie, Meade Lux Lewis, Albert Ammons, this was the music that was being played all across America. It was kind of like Scott Joplin’s music, kind of like rags in a way. Boogie-woogie took over and I heard that music on the radio and I didn’t even know that there was a piano in the house <laughs> till that music came on the radio. I discovered this piano in the hallway and I would sit at the piano all day with the radio on waiting for that music to come on. I started to learn how to play that music. I taught myself to play the piano by sitting and waiting every day for Boogie-woogie to be played. My hands were so small at that time, I was very frustrated. I remember I used to be very upset. That was the beginning of my whole musical life. I learned how to play Boogie-woogie when I was about three, three and half years old. Later when I was in grammar school and I began to take lessons, I wasn’t very happy with the music teacher I had at that time. So I really didn’t pay much attention. I would still play at the piano on my own. When I graduated from grammar school, I went to Englewood High School. The first concert, jazz concert, I went to was at the high school. My best friend played trumpet and that I would begin to play to the saxophone and he told me that there was going to be a concert on a Tuesday night and that we should go and hear it. I went to that concert and it was Stan Getz, I think it was Chet Baker, it was about 25 cents to go hear Stan Getz at my high school on a Tuesday night. So by the time I got to my second year, I was playing the tenor saxophone.

You said when you first heard Charlie Parker, he opened a door for you. What did you hear and how did that door open?

Henry Threadgill: When I first heard Charlie Parker, yes a door did open. The door to improvise music. I heard improvised music in a different way. Let me back up before Charlie Parker. My influence in terms of music was blues, Muddy Waters and Harlan Wolff, Jimmy Reed, this is what the music that I grew up on and this was the music that had the most impact in my life. I don’t know of anyone that had more impact on me than Harlan Wolff. <music playing> And then gospel music was born in Chicago. I grew up on this music. Mahalia Jackson is in Chicago. I heard her sing live I don’t know how many times and I heard Clay Evans and James Cleveland and all of these other great singers, but that music was not a improvised music. Of course, they had some variations that they would execute in this music, but Charlie Parker had stretched the boundaries. The music I had heard prior to Charlie Parker, the swing era music, it just had not opened up to that complex degree. That’s why I said when I heard Charlie Parker, a door opened. It opened up your ears as to what can you actually hear and what can you actually do.

When did you meet Muhal Richard Abrams?

Henry Threadgill: Well, I graduated from high school in 1962 and went to Wilson Junior College. This was a liberal arts two year college and they had an incredible music department. All of the art departments were incredible and the school was loaded with artists. I just can’t begin to tell you. Jack DeJohnette, Roscoe Mitchell, Joseph John and Melacap [ph?], they was Eddie Harris, Bunky Green. This was just some of the people that were there and we had a music club. We were charged with putting up different concerts. We would have classical concerts and we would have jazz concerts and I don’t know who it was. It could have been Melacap Favors [ph?] that suggested getting Muhal to play, but I didn’t know Muhal at that time. So he came with a quintet and that’s when I met him. We talked after the concert and he invited me to come to the Experimental Band which was rehearsing at that time at a place called C and C’s Lounge. This is where the Experimental Band started. This is the prelude to the AACM, Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians. So I went there and played for a bit and then he told me I could bring in some music. I brought in some music. It was very short period because it was in 1966 at this point and I had gotten drafted at this point. So I left. Right before I left the ACM had been on its way to being formed.

You were drafted into the Army. Is that what happened?

Henry Threadgill: I wasn’t exactly drafted. I was working at the University of Chicago Hospital trying to make some money so that I could go to the American Conservatory of Music in the fall and I was going to school part-time which was not allowed. If you didn’t have a full course then you didn’t have a deferment. The draft board in my neighborhood called me up, told me to come down and said “Mr. Threadgill, I got good news and bad news.” I said <laughs> “What do you mean by that?” He said “You’ve been caught working and not going <laughs> to school full-time. So they’re about to draft you.” He said “They haven’t, but they’re getting ready to draft you because they discovered that you weren’t in school.” So he said “What you can do is this.” He said “You’re a professional musician.” I said “I guess so.” He said “Well, join the draft as a professional musician just like doctors, all other professional people.” I said “What does that mean?” He said “A doctor can only practice medicine, a musician can only practice music. If you join the draft then that’s the only thing you can do in the service and if they violate that they have to discharge you with an honorable discharge.” I said “Okay.” He said “The only thing is you’ll have to stay one year longer.” The draft was two years. He said “That means that you’ll have to be in there for three years.” He said “But that can be adjusted, too. If any musical organization or institution call for your services, you can do two and a half years,” and that’s when the ACM wrote while I still in the service and said that they wanted me to come and teach at the school. So I was only in the service for two and a half years. <laughs>

I think the AACM is such an important organization in modern music. I’d like if you would talk about the vision that propelled the AACM and the philosophy that knitted all of you together.

Henry Threadgill: It was really Muhal’s singular vision concerning writing your own music and presenting your own music and developing and studying music, not jazz. The agenda was music. He believed deeply in that and we all picked that up. You can’t really say there was such a thing as a AACM school. Each one of us was school in our own. We had our different ideas and different approaches and it required a great deal of discipline in terms of the concept of democracy. Let me tell you what I mean by that. To complete you serve another person and to keep your ideas off the table and not to critique, to be completely at their service regardless of what they ask you to do. The idea is to let those people realize whatever their concepts are without any interference from anyone and interjected any kind of critiques whatsoever. Our job was to serve one another 100 percent. That was the basis of everything.

You know, what I find just so extraordinary about the AACM is that, well, so many things, but originality, personal vision was really stressed, but so was respect for other traditions and having a grounding in so many other musics and that’s really been a constant for your throughout your career.

Henry Threadgill: You’re absolutely right. The idea that all music from humanity is really what we were looking at and one great thing at the time, Chicago was so rich in terms of the blues and gospel music. We had that and the other thing that we had at the same time was the University of Chicago Contemporary Players Orchestra. They played the most advanced and the most difficult contemporary music from America and Europe. This is where I first heard and met The Rez, Paul Hindemith, oh, I can’t say. I met a number of great composers at these. We actually worked two or three blocks apart in the same area of the city. The first time I heard the live recording of Tia Lenore by Shermberg, [ph?] I heard it there. The first electronic music I heard was there that I heard The Rezes’ Electronique. The piece I heard that there and then the Chicago Symphony under Fritz Reiner at that time when I studied conductor. I was studying conducting in college and Fritz Reiner was playing some very interesting music and Mark Danun who followed him had a extremely contemporary repertory and it was on the margin that he actually commissioned Muhal to write a piece for the Symphony and he had something like 10 saxophones in the orchestra.

This period in Chicago was crazy because wasn’t Sun Ra playing then, too?

Henry Threadgill: I started going to Sun Ra’s rehearsal when I was about 15 years old, I guess, something like that. Sun Ra was rehearsing in the neighborhood right where I lived in Englewood. He rehearsed in the back of a meat market which sold wild game. So there was raccoons and bears.

Are you kidding?

Henry Threadgill: And possums hanging from the ceiling. No, I’m not. It was a Greek wild game market and the owner of it liked Sun Ra’s music and so at night in the back of the market he would let Sun Ra rehearse in the back of the market and it was extremely cold back there. That was the only downside. I used to go there with my friend just about two or three nights a week and sit there and listen to him rehearse and try to follow the music.

As we said, AACM, that approach to music, it’s finding your voice and a personal vision and I’m wondering what that process was like for you of finding a voice. I mean, it’s one thing to just say it, but then you have to trust your voice, develop that voice, learn to express it.

Henry Threadgill: Yes, that’s true to find a voice. The Midwest, Chicago, it was not New York. The fast pace of New York and New York is the marketplace. You go to New York with a finished product. It’s hard to go to New York and start putting groups together. That takes a lot of time and energy. So we had time on our hand and it was a cheaper way of living, too. We didn’t pay so much. So we had time and we took advantage of it. I tried different things. I tried all kinds of combinations of groups before I got to Air, the trio Air which everything started by Steve McCall and Fred Hopkins and then my whole life changed. <music playing> Steve had come back from Paris because remember in the ‘60s, Paris was it. New York was not it. The music world was in Paris. Everybody was in Paris. The track back in the ‘70s, there was a change. People started to return from Paris and New York all of a sudden became a new migration center. New York got reenergized. So we came in about ’70, I think, ’74. I think ’75, ’75, Air. We played a concert. It was in January-February and it was really cold and it was a lot of snow. It looked like Chicago. The snow was up to your knees and we play La MaMa, at La MaMa Annex and some people said nobody’s coming to hear you all because nobody ever heard of you people from Chicago named Air. We said “That’s okay. We’re going to play anyway.” It was cold in the place. They didn’t have any heat. We had three nights, Friday, Saturday and Sunday night in this place. The people that came Friday night they went out and spread the word. Saturday night there was a line down the street and Sunday night it was a line down the street. Some of the people kind of like philanthropists type of supporters came in and heard us and the next thing you know we were playing at Carnegie Hall in April. <laughs> That’s how fast they turned around. <laughs>

That’s amazing. I know you had said you don’t like the word jazz and you don’t consider yourself a jazz musician anymore. Can you explain why and what your thinking is about that?

Henry Threadgill: The word jazz had been abused and misused. That’s why I don’t like it. It’s became like a pot that people throw everything and it’s lost its distinction. Just put something or put that over there, soft jazz, hard jazz, this kind of jazz, that jazz. So that’s why I don’t like it and that’s why I don’t use it. I prefer the word creative music. Creative improvised music and would say improvised music.

You’ve also said that live music is the way to hear music and you never made a record with the society’s situation dance band. You only performed live with them.

Henry Threadgill: I never wanted to make a record with that. I grew up going to dances when I was kid, right, and there would be live music, great bands would be playing. We would go to dances and so I didn’t want to record this. This was just for people to react to it and dance. Studios have a way of becoming self-conscious and you don’t have an audience. How do you go into a studio and play dance music if there’s nobody dancing? <laughs> You know what I mean? You can’t even tell if you’re doing a good job. <laughs>

Your work encompasses such a wide range of music with a wide range of compositional techniques and a wide range of groups. In fact, many groups throughout your career.

Henry Threadgill: I’m going to just give a little quick overview history of the groups that I’ve had. The first group I had was Air. Air, the compositional techniques that I was developing were mostly in the major minor world and a chromatic world. Chromatic world sometimes sound like you’re sound like you’re doing something that’s free. I never did play free music. After that I came to Sextett and I was still doing writing music in the same kind of way and I also had a second group that I never recorded which was a great group called the Wind String Ensemble. That was tuba, cello, violin, viola and I played alto and flute. Now, the Sextett which I thought of as a reduced orchestra, it had a wind section, a brass section, a string section and percussion section. That’s how I thought of it. The percussion section had two drummers. I considered it one part. It just had two people playing different things the way you would have in a orchestra. It would be one person on the snare drum, another person be on temp and another person be on tambourine. You could have four people playing and it’s still one part. It’s the percussion part. Then I had the strings which was the cello and base and then the trombone and the trumpet was the brass and then I covered the reeds. <music playing> But the music I was writing at that time was still within the major minor system of music. Major scales, minor scales and combinations thereof. After that group came Very Very Circus. Very Very Circus, again, I was still stretching the boundaries of the major minor system and then when I got to Make a Move, I got as far as I could actually go in terms of this major minor idea and in this period that I made major discoveries about new was to write music and that led to the group Zooid and the system of music that started with Make a Move, but I worked everything out with Zooid. So every group that I had it had something to do with how far I had made it compositionally. I would change groups because the compositional ideas had changed. When I got everything I could out of something then I would change. I would never just change for novelty. I never even thought of doing anything like that. After I completely exhausted the orchestrational and compositional techniques that involved that particular ensemble then I would start to move to the next level and I’ve been fortunate that I could do that that I saw something beyond the horizon to move to.

You mentioned Zooid and how long for, what, 18 years.

Henry Threadgill: At least 15-16 years now.

How did that band start and what were you looking for?

Henry Threadgill: Well, first thing was I was looking for the players because I knew what the instruments I was hearing. So Tyreek Bemberdene, the oud player, who is now in Morocco. He’s a filmmaker, also a great filmmaker. Jose Davila, the trombonist, tuba player. He had been with me in Very Very Circus and other configurations and guitar player Liberty Ellman. Liberty Ellman recommended Elliott Kavee to trombone with us. The first Zooid record where Deaf [ph?] has appeared from Cuba, he was the first drummer with us and then I found Elliott. Dana Leone, the trombone and cello player, great artist. So I had cello, guitar and oud as the string section and tuba, drums and myself. That was the sound I was after. So we rehearsed for one year in New York City before we played. They had to learn a new language because, see, I had come up with another musical language and it wasn’t just you could just come in and read this music. You had to understand the language. We spent a year learning the language and how to work with it because we had to improvise in this language and after a little over a year and something we played our first engagement somewhere. I don’t even remember the first place, but these were special people. I don’t know how many people would have stayed with me for over a year just rehearsing with not the promise of a recording, not the promise of playing a concert or anything.

Again, you’re very deliberate in the way you create your compositions. So you create a composition that has room for the musicians you play with to improvise within that structure, that musical structure that you create. Is that a fair way of saying it?

Henry Threadgill: That’s correct. Yeah. There’s room for improvisation. Yeah. Most of the time the music appears more seamless. A lot of times you can’t tell whether we’re improvising or reading music. It’s a greater ideal is to go for something like that, something that’s more seamless.

When you’re composing, do you find yourself consumed by it as you’re working on it or do you leave it aside for a while, walk away, maybe leave it for a week, a month and then come back to it? I’m curious how that works with you?

Henry Threadgill: Composing is like going back to square one every time. <laughs> You don’t know what it’s going to be. You accomplish something and you say oh, wow. That was a nice step that I pulled back there, that step A and B. I think I’ll try that the next time. Next time there’s no room for A and B. <laughs> No place to execute A and B. So every time there’s a new experience and the music, see, the composition starts to dictate. You, the composer and writer, you have control, but you only have so much control. You ever heard of writer, I’m talking about literary writers, say that like they created this character. Now the character is in charge. You ever heard a writer say that?

Yes. Definitely.

Henry Threadgill: The same thing happens with the music. You have to let the music go where it’s going, stop trying to control it sometimes. I never know quite what it’s going to be. Sometimes like, say, I leave things intentionally so that I can get a fresh look at it because it does get consuming and sometimes you just need to step back.

And I’m assuming you’re hearing this in your head as you’re composing.

Henry Threadgill: Yeah.

When you go and you were actually giving the music to the musicians does it happen that you think oh, that sounded very differently in my head. This isn’t quite working when I’m hearing the musicians do it.

Henry Threadgill: You know, my philosophy is this for one thing. The object for me is to make music. So I write it down, I bring it and somebody make a mistake. I say oh, that’s wonderful. Let me change this and put the mistake in because that’s the object for me. I’m not stuck on what I did. Remember music means nothing until you lift it up off the paper. It has no meaning. That’s what a conductor is doing. When a conductor is standing up there with a score in front of it and the orchestra. I don’t care whose music it is, van Beethoven’s. What the conductor is doing is saying too many violins is playing right there. Let me have less second violins. Trumpets start doubling so and so over there. He basically said a half a teaspoon of salt and two teaspoons of pepper. The composition said a whole teaspoon of salt and three teaspoons of pepper. That’s what’s on the paper, but when you start to lift it up you find out it won’t bake. <laughs>

And is that what you mean when you said artistic process and product are inseparable?

Henry Threadgill: Yes. Yes. It’s exactly. Yeah. The process. You have to find out, you imagine something, you write a script and the writer, he sits in the audience and as actors come on stage and he laughs at this comedic lines. Well, he wrote it, didn’t he, but nobody else is laughing. <laughs> So you have to really look around and see if it’s working. You got to put it up. You have to play it live. That’s the other thing about live music, live art. You have to resurrect it to find out will it stand that it has to be put up and also the impact. I listen to records when a kid, but when I used to stand up as a kid in front Harlan Wolff and Muddy Waters, it was nothing like that. I wouldn’t even be in time anymore. I’d be standing there. It’d be just like I walked through some portal or something.

That’s a nice way of putting it. You’ve spent a lot of time in India, in Caracas and traveling throughout the world and, obviously, all these places have different musical rhythms and I wonder about immersing yourself in those cultures and the influence that has on your work.

Henry Threadgill: You know, it’s almost impossible for me to quantify in any kind of way what I learned from different cultures. When we say music, music is a part of some culture and if you emulate on the surface certain music it becomes obvious that you’re just like pandering to something or doing something that’s so obviously not very serious. Like you said in places like India and stuff, I mean, I listen to music there, but it’s not just listening to the music. It’s the way people walk. It’s the rhythm of the language. It’s the spices in the food. It’s all of those things. All of those things is what inform your creative process, not just the obviousness of like classical music or something. No, it’s far more than that. I think in dance, theater, all of these different mediums, we learn from other parts of humanity on the globe. As you reach out you get a bigger reward the further you reach out. <laughs>

Well, as listeners we get big rewards, too, from the work that comes out of it and you’ve received so many awards I can’t even begin to mentionable of them, but I do want to mention two and one was the 2016 Pulitzer Prize in Music. Congratulations. I know you don’t like to call yourself a jazz musician, but you’re the third living jazz musician to receive that and it was for “In for a Penny, In for a Pound” which you recorded with Zooid. <music plays> That had to have been really gratifying for you.

Henry Threadgill: Oh, it was. It certainly was. I mean, I wasn’t expecting it. I remembered that the record company had asked my copyist for the score and a audio file on it, but that had been like a year back and I didn’t think about it. When they called me up, a matter of fact it was the record company called me and was telling me to see you won the Pulitzer Prize, but I said “For what?” <laughs> Did I do something right or did I do something wrong? <laughs> It was really something. It’s a level of recognition for what you do. There’s no words for it. It’s really great, a great honor, a great honor. That honor and the honors of being the Harlem Stage and the Welico [ph?] Arts Center where they have your work perform where the musicians came and played on my work to honor me. That’s another great honor. When people in your time play your music then you figure you must be doing something right. <laughs>

Well, you really must be doing something right because you have been named the 2021 NEA Jazz Master and I wonder if you can say what that means for you.

Henry Threadgill: Well, this honor is the highest honor that the country gives. The honor is not just to me. I didn’t get here on my own. All of these people that’s been in my life, all of the influences, so much I’ve learned, I can’t even articulate and give all the names of all of the teachers, friends, parents and even silent supporters. That’s who’s standing here that sitting here taking this award with me. It’s not just an award to Henry Threadgill, it’s that part of this community and this country that produced and nurtured Henry Threadgill is why I got that award. That’s what that award means. It means that you said something about not just me, but all those people that did something to make this a better place for everybody in this country through art.

And I think that is a great place to leave it. Henry, many congratulations and thank you for years of your beautiful, wonderful work.

Henry Threadgill: Thank you, Jo. My pleasure.

That was 2021 NEA Jazz Master Henry Threadgill. Henry and all the 2021 NEA Jazz Masters will be honored with a virtual tribute concert on April 22, 2021. The Arts Endowment will again collaborate with SF Jazz on this virtual event which will be free with no registrations or tickets required. For further details keep checking arts.gov or follow us on Twitter at NEA Arts. You’ve been listening to Artworks produced by the National Endowment for the Arts. I’m Josephine Reed. Stay safe and thanks for listening.