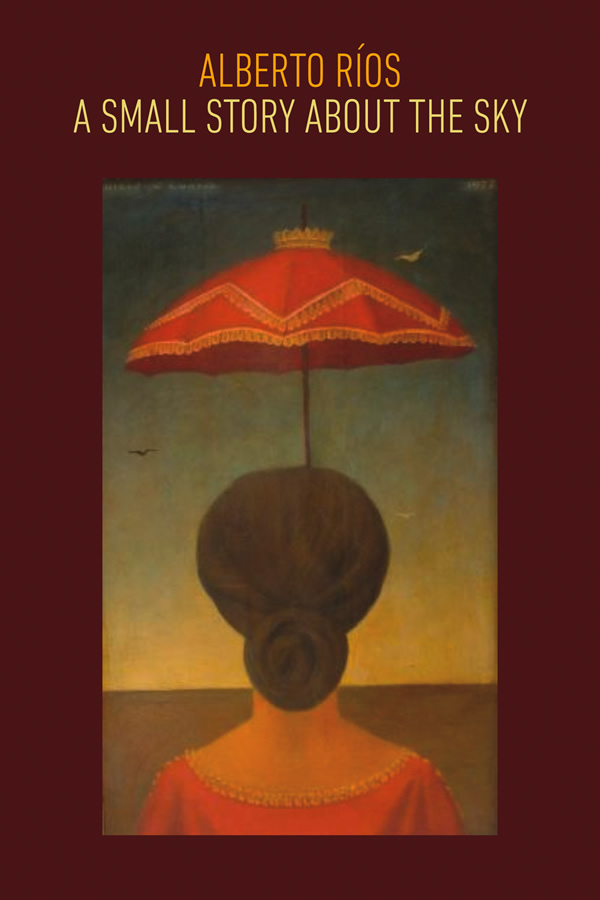

A Small Story About the Sky

Overview

The poetry of Alberto Ríos—Arizona’s first poet laureate—has been featured in film, set to music, and included in more than 300 national and international anthologies. A beloved teacher at Arizona State University in Tempe, winner of numerous awards, including a National Endowment for the Arts creative writing fellowship, and the author of many books of poetry and prose, Ríos is known for work that is charming, magical, and inventive. A Small Story About the Sky is his 13th book. “The poems [in this collection] are playful, nostalgic, witty, imaginative and funny. It’s easy to envision many of them being enjoyed by children (as one hopes they are bound to be)” (Rumpus). "Ríos delivers another stunning book of poems, rich in impeccable metaphors that revel in the ordinariness of morning coffee and the crackle of thunderous desert storms…. This robust volume is the perfect place to start for readers new to Ríos and a prize for seasoned fans" (Booklist). “Rich, surprising, metaphysical, his poems show just how deeply, delicately, tenderly he cares for what is” (Wichita Eagle).

“Something is always broken.

Something is always fixed.”

— from A Small Story About the Sky

Introduction

“We give because someone gave to us. / We give because nobody gave to us.” – from Alberto Ríos’ poem “When Giving Is All We Have” in A Small Story About the Sky

Sprinkled with hints of magic realism and deeply rooted in the desert landscape of the Southwest, A Small Story About the Sky is Alberto Ríos’ 13th book of poems. It is as much a celebration of the everyday—drinking a morning coffee, feeding birds, going to the market—as it is a philosophical exploration of the things that do not exist but are very much real: ghosts from dust caught in the projector at a movie theater, the journey down the drain of washed away detritus while showering, the lines that separate us. The pages are filled with honeymoons and fiestas, fences and mirrors, beetles and crows, remedies and prayers, modern observances and ancient whispers, and a misheard weatherman predicting “rain and a chance of lizards.”

Ríos wrote many of the poems in this collection for specific occasions during his role as Arizona’s first poet laureate. These occasional poems can be found throughout the collection, particularly in the sections called Poems of Public Purpose. “Stardust and Centuries,” for example, was written for a women’s empowerment group; “On Gathering Artists” was for the Arizona Commission on the Arts; several of the flora and bestiary sonnets, as well as “Understanding the Black-Tailed Jackrabbit,” were for the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum; “Knowledge Neighbors” was for a library; and “Border Lines” was for the grand opening of the Nogales-Mariposa Port of Entry. Ríos recited “Border Lines” in front of an audience of thousands with former Mexican president Vicente Fox by his side. “Occasional poems can often feel forced, can venture into the realm of rhetoric, which is not where we generally want the poem to go,” Ríos’ editor, Michael Wiegers, told the NEA. They’re “tricky to navigate, but he really pulls [them] off.”

Some poems have taken on a public role of their own volition, such as “When Giving Is All We Have,” which has gone viral on social media. BuzzFeed included it in a piece with the title, “12 Painfully Beautiful Poems That Will Give You So Many Feelings.” Originally written for a play called Amexica, “The Border: A Double Sonnet” was used by the rock band U2 during the tour of its album The Joshua Tree. Ríos learned the poem was being used when his son’s friend, who was attending a U2 concert, sent a picture to Ríos’ son of the poem projected onto a giant screen.

Most of the book is written in two-line stanzas called couplets, which lend themselves to Ríos’ “investigations of duality: of life, of mind, of spirit, of circumstance, of location and the physical elements” (Rumpus). “The Thirst of Things,” for example, imagines the Sonoran Desert remembering itself when it was an ocean during the Paleozoic Era, a demonstration of the “fierce what-was in all of us.” “The Border Before” remembers the original intent of the fence that divides Mexico and the U.S., “a way to keep cattle safe,” and reflects on what it has ultimately become. But just as the spaces between the stanzas can say as much as the stanzas themselves, Ríos reminded us that it’s not just duality he’s after. “It’s not black and white, not either/or—it’s also/and,” he told the NEA. “I’m a product of the Southwest, the border in particular, raised in a multiracial household. I was in-between languages, in-between countries. We are surrounded by stabilized, tired ideas. For me, everything had possibility. Everything could be looked at in a different way.”

Ríos’ poems sometimes look at things in a different way through personification: the attribution of human-like characteristics to something non-human. This can be seen in poems like “Winter Lemons;” “The Thirst of Things;” and “Leaves and Leaves,” in which leaves on a tree are described as “webbed hands” whose intent are to block the speaker in the poem from seeing the tree itself. Ríos attributes his ability to humanize plants, animals, and inanimate objects in part to the Spanish language. “In English, we think we own the world” Ríos told BOMB Magazine. “If I take a pen and drop it on my desk, I would say: I dropped a pen.… In Spanish, it might be something like ‘Se me cayó la pluma.’ Don’t think of me, right—think of the pen. We were both there together, partners in the moment. The pen, it fell from me. Maybe I dropped it, but I don’t know for sure. Maybe the pen wanted to fall. It allows for that possibility of an inherent life in things, and more generally, that we maybe don’t know everything.”

The six “Desert Flora” and “Desert Bestiary” sonnets use a combination of personification and metaphor to achieve their effect, with lines like “Prairie dogs at attention are the patient ears of the earth,” “Tarantulas are awkward left hands in search of a piano,” and “Scorpions are lobsters sent west by the witness protection group.” As their titles suggest, the poems are sonnets, but they are also compendiums of greguerías, short single-line poems that “use high drama next to humor, and have resounding depth,” said Ríos (Phoenix New Times). The product is a traditionally Anglo form (the sonnet) married with a traditionally Spanish form (the greguería). “This is the kind of poetry that works like magic on children,” which is “a profound compliment, because metaphor is very easy to understand as a concept (look at something, think of what it reminds you of) but very difficult to execute as a practice” (Constant Critic). “In the long haul of my work,” said Ríos, “I want to say that this place is a life.”

- The first few poems in the collection narrate moments in which something familiar—a spill of birdseed, a cup of coffee, a tree—are suddenly rendered strange, beautiful, or simply anew. Did these poems succeed in helping you see beyond the familiar? Can you find other poems in the collection that also do this? Can you remember a time when your perception of something familiar was changed? If so, how?

- In “Sudden Smells, Sudden Songs” (p. 7), Rios writes: “We stand up, familiar to ourselves // Then sit down strangers. We are / Two people. Maybe more.” What do you think Rios is getting at here? Have you ever had a similar experience? Can you find other poems in the book in which the speaker thinks about or encounters different versions of himself?

- “On Gathering Artists” (p. 29) might be described as an ars poetica: a poem about poetry, the poet, and/or the role that poetry and the poet can play in our lives. What do you think this poem is saying about poets and the role poetry can play in our lives, relationships, and society?

- “Where Sleep Is” (p. 18) and “Understanding the Black-Tailed Jackrabbit” (p. 118) are poems that contain magical elements alongside realistic ones. Do you see other examples of this in the book? As a storytelling technique, what do you think magic might allow Rios to accomplish that realism alone cannot? Can you think of other books you’ve read, or other art forms you’ve encountered, that use elements of both magic and realism?

- The two “Poems of Public Purpose” sections of the book are made up of poems that Ríos wrote for specific groups or occasions (for example, “Stardust and Centuries” (p. 36) was written for a women’s empowerment group; “Knowledge Neighbors” (p. 101) was written for a library; and many of the “Desert Flora” and “Desert Bestiary” poems were written for the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum). How do you think a poem can enhance an event or occasion? If you were to write your own “occasional” poem, what occasion would you mark and why?

- The Desert Flora (pp. 33, 94, 98) and Desert Bestiary (pp. 31, 35, 96) poems pay homage to the plants and animals of the desert landscape—scorpions, millipedes, rattlesnakes, rosemary bushes, and paloverde trees, to name a few. Did Rios’s descriptions make you see these plants and animals in new ways? Did any of the descriptions in particular resonate with you?

- The Desert Flora (pp. 33, 94, 98) and Desert Bestiary (pp. 31, 35, 96) poems are sonnets—traditionally European forms of poetry often associated with themes of love. But they are also groupings of greguerías (grey-geh-rEE-ahs)—short one-liners containing humor and metaphor commonly used in Spanish and Latin American literature. Why do you think Ríos chose to structure these poems as sonnets and greguerías? What is the effect of using both forms?

- The poem “A Small Story about the Sky” (p. 41) shares a title with the collection. How do you interpret the story the speaker tells in this poem? Does this story shed light on other poems in the book?

- The poem “November 2: Día de los Muertos” (p. 58) is about the Day of the Dead or All Saints’ Day. Are you familiar with this celebration? If so, how does the poem conform to what you know about the holiday, and/or how you’ve seen it portrayed elsewhere? How do you think your own ideas about death have been shaped by your culture?

- In “The Border: A Double Sonnet” (p. 63) Ríos explores what “the border” is through the use of anaphora, a rhetorical device in which a word or phrase is repeated at the beginning of every clause. Were you surprised by the different ways in which Ríos defines the border in this poem? What is the effect of presenting these definitions in one long list? Did the poem reinforce your perception of the U.S./Mexico border or make you see it in a new way?

- Much of the collection is rooted in Arizona—where Ríos grew up and still lives today— as well as in Rios’s Mexican family history. Looking at the poem “The Thirst of Things” (p. 20), what do you think Ríos is saying about the relationship between the present and the past? Between the American and Mexican parts of his identity? What do you think he means by “the fierce what-was in all of us?”

- The great-aunts in “The Border Before” (p. 85) remember a “time before the fence” and the original purpose of the border. Yet, Rios writes, they are “no longer here/ To tell their story.” What is the consequence of losing these voices? Do you have any relatives who are or were the last to remember a significant event or the original purpose of something? How might their experiences and knowledge be preserved for future generations?

- What do you think Rios is saying about community in the poem “Knowledge Neighbors” (p. 101)? Where do you see depictions of community elsewhere in the book? Do you recognize your own community in these poems?

- Do you think the book reaches a resolution in the final poem, “The Broken” (p. 123)? Why or why not? How do you interpret the poem’s last lines, “Something is always broken./ Something is always fixed?”

Discussion questions adapted from source material provided by Copper Canyon Press.