Resilience and Opportunity

Former boys dormitory at the Theodore Roosevelt Indian Boarding School in Arizona. Photo © Thinc Design, all rights reserved

According to a recent story in the New York Times, at one point in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there were more than 500 boarding schools for Native children across the United States, more than three quarters of which were federally supported. Children were often forcibly removed from their homes and sent to these schools where they were stripped of their original names and given English-language ones, their traditions and languages were forbidden, and contact with the families left behind was severely curtailed. The children were often engaged in forced labor, and the chief educational goal was assimilation into non-Native culture. Some children died under the harsh conditions; those that survived were left traumatized, a trauma that continues to haunt generations of families still today. As U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo) noted in the Times piece, “Federal Indian boarding school policies have impacted every Indigenous person I know. Some are survivors, some are descendants, but we all carry this painful legacy in our hearts and the trauma that these policies and these places have inflicted.”

The Theodore Roosevelt Indian Boarding School, one of the federally supported schools that remains in operation, is located in Arizona. Sharing the site is the now-decommissioned U.S. Army’s Fort Apache. For decades, these twin representatives of colonial power kept strict watch over a people whose land had been usurped, reducing their lives to a subsistence level governed not by the values the Apache had held for centuries but by a system of laws and regulations determined to break the people’s spirit, with the supposed intention of creating “good Americans.” Despite everything, the Apache people have persisted. Today, with support from an NEA Our Town grant, the agency’s creative placemaking grants program that supports activities that integrate arts and design into local efforts, the Fort Apache Heritage Foundation is working with a range of partners to actively reclaim the site now known as the Fort Apache and Theodore Roosevelt School National Historic Landmark for its community. They will be turning a place of loss and grief into a place of rejuvenation, reconnection, and healing.

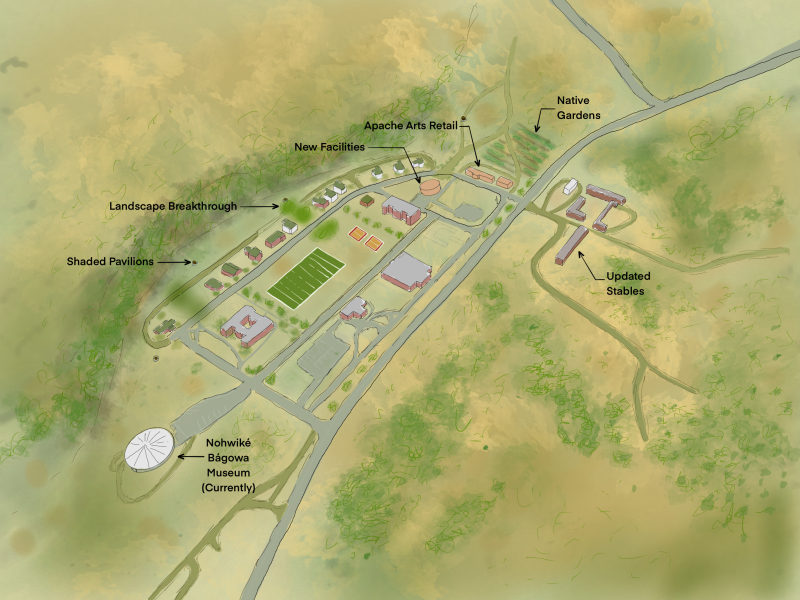

Map of Fort Apache Historic Park. Image © Thinc Design, all rights reserved

According to Executive Director Krista Beazley (White Mountain Apache), the foundation’s mission includes education, health and wellness, preservation, and economic development. They also co-manage both a gift shop that sells local crafts and Nohwike’ Bágowa, the White Mountain Apache Tribe Cultural Center and Museum. The foundation is actively engaged in rehabilitating the natural landscape as well as existing historic structures on the site’s 300 acres of protected land to meet community needs such as housing, office space, athletic fields, and places to gather. “The tribe is very in need of spaces just to do programs,” Beazley explained. “On the reservation, we have a shortage of living quarters. It’s so sad that close to 1,200 tribal members are on a waiting list for a home to be built. Most of our structures that are rehabbed we try to rent to commercial and residential tenants.”

The foundation’s board secretary, John Welch, a trained archaeologist who has worked with the tribe for decades, noted that reclaiming the entirety of the site for use by the tribe is at the heart of the healing process. “In the Apache way of thinking about the world, there’s no separation between the land, the spirit, the mind, and the body. To the extent that we can heal the land at and around Fort Apache and eliminate the boundaries that have been erected between Fort Apache and the rest of the land, [it will] enable people to be healthy through greater connections to the land.”

He added, “We want to turn the place kind of inside out, because it was set up architecturally and institutionally to be a bounded place where people were brought in and their attentions focused in on the military power structure that was at the core of it, and then the school power structure.”

In order to make sure that the foundation’s plans are in alignment with community priorities and values, the Our Town grant has been used to support a series of listening sessions facilitated by Thinc Design, a New York City-based design and exhibits studio. Welch said, “We wanted to hit a reset button and say, ‘Hey what are we missing? What are we forgetting about?’ And to talk to people, to go a bit more systematically through segments of the community: religious leadership, community leadership, youth leadership, artisan leadership, and representation of communities that aren’t normally brought into the fray, including [those] that are unempowered, even in an unempowered community of Apache people.”

Based on these conversations, a number of community priorities arose, such as language preservation. “It’s a bittersweet area, but still they consider Fort Apache as the cultural site, and language preservation is where it should all start,” said Beazley. “One of the elders, I remember him saying, ‘When you come on to Fort Apache, I want to put a sign that says when you pass this sign, you have to speak Apache.’”

Rendering of proposed gathering space. Image © Thinc Design, all rights reserved

Welch added another community need is “lots of spaces for intergenerational contact, lots of places where elders and kids would feel comfortable interacting in shady green places with access to water and places to sit down. It’s a community of over 10,000 people, and there’s just no place for people to go and play and sit in the shade and watch the kids and be Apache.”

Even though the project is in early stages, and was delayed, as most everything was, by the onset of the COVID pandemic, there are already signs of healing. For example, as new buildings are planned and existing ones rehabbed, the designs reflect Apache ideas of harmony and balance, with a preference for organic shapes. Describing a site visit by a group of tribal engineers to a possible location for a STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) lab, Welch said, “They’ve never been inside a building in Fort Apache, and they walk in and they’re just like, ‘This is freaking cool! Look at the cool structure. Look at the thick adobe walls, these gigantic, thick timbers.’ To me, when somebody walks in and lights up in a historic building and says, ‘I can share the vision of this place as something that’s going to be good for kids, have them not be afraid that something bad is going to happen to them because they’re at Fort Apache,’ that’s success.”

Beazley also reported that the local health center has organized foraging trips for traditional foods, such as acorns, and the foundation has partnered with the local farm to reintroduce Apache foodways such as wild tea and traditional cornbread. Even the annual fun run represents Apache tradition as, according to Beazley, the tribe was originally nomadic, traveling to different areas for food sources until they were confined to the reservation.

The project’s next steps include securing funding to continue restoring the site’s historic buildings. They are also working to make sure that even more community feedback is integrated into the planning process. Beazley noted that she also hopes to strengthen their relationship with their partners.

Though it will take years for the Fort Apache site and community to be completely healed, the healing is well underway. As Welch put it, “People are starting to see the place as opportunity, as [a source of] pride.”