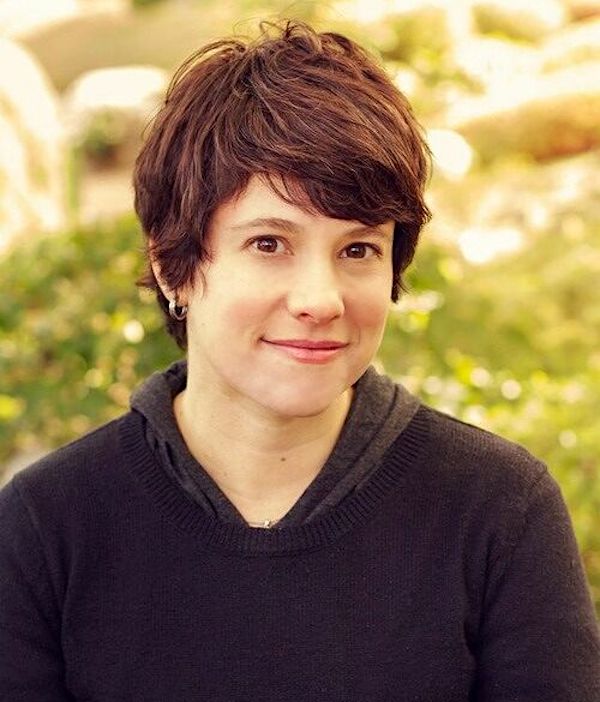

Christina Henry

Photo by Kathryn McCallum Osgood

Music Credits: “NY” composed and performed by Kosta T, from the cd Soul Sand, used courtesy of the Free Music Archive.

Jo Reed: From the National Endowment for the Arts, this is Art Works. I’m Josephine Reed. On this Halloween Day, I’m speaking with prolific horror author Christina Henry. Christina’s work evokes a profound sense of fear and atmospheric tension--drawing on her fascination with haunted spaces, eerie forces, and the way horror reflects our deepest anxieties. From her childhood love of horror movies to her nuanced approach to character-driven storytelling, Christina shares insights into the allure of horror, why some are drawn to its thrills, and how her stories work to strike a balance between psychological tension and emotional depth. So, let’s peer into the shadows of storytelling with Christina Henry!

Christina, first of all, thank you for joining me.

Christina Henry: Thank you for having me.

Jo Reed: You're welcome. Your most recent book, because Lord knows you are prolific, The House That Horror Built, draws inspiration from the classic horror movie stories. First, can we begin by you giving us just a little synopsis?

Christina Henry: The House That Horror Built is about a young woman who's a single mother, it's set during the pandemic, which is pretty key to the story. She really needs a job, and she takes a job with a very mysterious reclusive horror director who has recently moved to Chicago, and basically, she's signed up to be his house cleaner.

Jo Reed: What elements of the horror genre in film most fascinated you while you were writing this novel?

Christina Henry: I think in a lot of ways, this novel really draws from just almost my own personal history with horror movies and horror books. Like a lot of horror authors, especially horror authors of a certain age, I am a Gen Xer, I grew up reading Stephen King, I watched a lot of horror movies on videotape as a kid. And I tried to draw a little bit from a little bit from sort of all the horror that I like, but I think specifically, it's a throwback in a way to sort of what I think of as just sort of spooky movies, not necessarily outright scary, right? Like the Vincent Price era, Boris Karloff, actually reference Val Lewton movies in the film, that's the kind of thing I was thinking of, you know, movies that were more about atmosphere than about jump scares or gore.

Jo Reed: Well, this book certainly has a lot of atmosphere. Our mother, whose name is Harry, and her son is Gabe. And their relationship really adds this very strong emotional layer to the book. How do you balance that kind of character development with the atmospheric tension that is needed in horror?

Christina Henry: I think that there's a natural tension that develops from her need to protect her son, you know, in so many ways, in all the ways that parents seek to protect their children, right, to have stability for him, to make sure that nothing bad happens to him. But for me, when I go to write a story, the characters always come first before the plot, I usually think of a character before I think of a plot, and a lot of times the plot springs naturally from the character's choices. And I have a teenage son myself, he's 18 now, and I do think to a strong degree I was drawing on, you know, the dynamics of our relationship, that push and pull that happens when your kid is no longer little, and they think that they know everything, and they think that they can make their own decisions, but they still need you. So I really wanted that relationship to be the heart of the book, because every choice that Harry makes is in service of Gabe, it's about making sure that he has the happiest life that she can provide him.

Jo Reed: Well, you also don't shy away from the very real financial struggle she has as a single mother. And I was really struck by how clear you were about how time-consuming being poor is. And I think that's so often overlooked.

Christina Henry: Yes. When I was younger, my husband and I struggled quite a lot. Just the way a lot of young people do, you know, getting themselves established. And it's so hard to be poor in this country, there's no real safety net. And I think that especially during the pandemic when this book is set, that really came home to a lot of people, that there was nothing there to catch them, and that they really had to take a lot on themselves. And if you had the kind of job that Harry did at the beginning of the story, she talks about how she was a waitress in a restaurant, and if the restaurants are closed, you know, there's nothing for you to fall back on. And it's so hard, I think, when you're a single parent, to not only take all that burden of, you know, the finances, but sort of the emotional stress that comes with that. And I think there's a constant temptation, and I do talk about this in the book, to make your kid, you know, more of an adult than they actually are. And she tries so hard in the book to keep a line between adult responsibilities and kid responsibilities. Like, you are a student, that's your job, your job is to go to school. Your job is to do well, my job is to worry about the other stuff. And that's, I think, so important, too, to their relationship dynamics. Because he's growing older, and he's aware of what, you know, he sees it. He sees the stress on her, he sees what's involved. But she wants to make sure that he can still be a kid.

Jo Reed: Yeah, I was really moved by that. Harry trying to protect her son, and you also see how smart and aware Gabe is.

Christina Henry: Yeah, I mean, kids notice everything you do. If you have spent any time with kids, even if you've just babysat a kid for an hour, you don't have none of your own, kids notice everything that you do. They're always watching.

Jo Reed: Well, they're both great fans of horror films. And Javier Castillo is the film director who she goes to work for, tell us a little bit more about him.

Christina Henry: So he has this mysterious tragedy in his past, which I don't want to get into too much, it's sort of revealed over the course of the book. His wife and son are missing, and there's not a lot of clarity about why. And there's also a crime that his son potentially committed, certainly strongly implied, and so he's very alone, and he's living in this house full of all this stuff that he has collected. And he hires Harry initially basically to come and help him clean his house full of stuff, all of these horror props that he's collected, other things. It’s sort of atmospheric by design, right? Because you have a house full of costumes and props and all kinds of other things from…

Jo Reed: From horror movies.

Christina Henry: Yeah.

Jo Reed: And the house itself really becomes a character, at least I thought so when I read it.

Christina Henry: Yes, I do think that, and I think that the way people live in houses is what gives them their character. I think a lot of times we think that just because a house is old or whatever, that it has a character, or that if it's new, it doesn't have character, but I think it's the way people choose to live inside houses gives them character. And the way Javier Castillo has chosen to live is in this very isolated fashion, like I said, sort of surrounded by things, things that he clearly prizes, things that may give him comfort, but it's not the same as the contact of other human beings.

Jo Reed: Right. It's almost as though the things reify him.

Christina Henry: Yeah.

Jo Reed: They're his worshipful chorus.

Christina Henry: Yes. And that's so key to who his character is because he is a person who does think that he's a little bit above everybody else, by virtue of his creations.

Jo Reed: Well, okay, I really am interested in why people are drawn to horror. For insight, for people like me, because I'm not, but I'm really curious about it. I don't like being scared. I get scared so easily. “Abbott and Costello meet Frankenstein” can put me into a fright. It has. Full on true. So I really want to understand, why do you think people are attracted to stories that scare them while other people like me would really just rather avoid the whole thing?

Christina Henry: Well, I guess I want to ask another question before I answer yours, which is like, do you ever like to go on like roller coasters or any kind of…?

Jo Reed: Occasionally, yes, but never upside down. I'm really fussy.

Christina Henry: But you'll get on a roller coaster that goes up and down, and there's a little bit of a thrill, there's a little bit of a "Whooo!," you know, you've got that part where it's going up the hill and then it goes down really fast and it maybe takes the turn a little tight. I think that we all seek out some equivalent of horror to some degree in our lives. We're always seeking a little bit of a thrill, a little bit of something that sort of gets your heart rate up, gets you going, but it's controllable. It's not actual terror. It's not something that awful that's actually happening to you. And I do think to some degree people seek out horror because it's a stress reliever, believe it or not. I think that it gives them something that's like thrilling in a controlled way. I think a lot of Gen Xers spent a lot of time in the video store when we were kids. My favorite section to go to was the horror section, because it had the coolest covers. It always had the best art on the box, it always had sort of the best marketing. And little girls in the 80s, we used to take two or three videotapes and have a sleepover and then we'd all sit on the floor and scream together while we were watching the movie-- you know, honestly, some of them were not that good. But it was the fun of it. It was the fun of being together, and I do think that that's also a key part of horror is community. Horror isn't meant to be watched by yourself in your house, although I do a fair bit of that myself. I like to just have “Scream” on in the background, that's very comforting to me. But I think that the thrill of going to a film where you're all sitting together in the dark, and you're all gasping in the same places, and you're all jumping in the same places, and then it's over and you all breathe this big sigh of relief, and then you laugh, right? There's usually actually a lot of laughter at the end of a horror film because it's like, "Whew, we all got through that together."

Jo Reed: I'm finding this so interesting, because I think the problem with me is I don't feel like it's controllable. I feel like whatever I'm seeing inside that movie, I'm bringing home with me.

Christina Henry: [laughs] I mean, I think there is some of that. Certainly there are some films that have been… Not too many films in my life have really, really scared me. Just a few. Usually it's just a little thrill. But my son, who does watch quite a few horror movies with me, says he actually prefers to play horror video games because he likes to feel like he's controlling what happens. He wants to feel like he has some kind of narrative control of the situation, even though there's still things popping out and other things that he can't control within the game. He wants to feel like he has some agency over what's going to happen next, which is pretty interesting to me.

Jo Reed: It's interesting, because years ago I decided I'm facing my fear, and I was going to read Bram Stoker's Dracula.

Christina Henry: Which is very atmospheric.

Jo Reed: Yes, and I was three quarters of the way through the book and I could not finish it, I just said, "No, I can't, I can't." And my then husband said, "Jo, I just want to make sure you understand, they vanquish the vampire at the end." And I looked at him and I said, "But suppose they don't in my copy of the book, then where will I be?" And I really felt that.

Christina Henry: But that's such a wonderful-- to me that's a wonderful feeling. I do think everybody's a little bit different, but to me that feeling of, "Oh my gosh, what will happen next?" is the best. I love that feeling of "Maybe they won't beat him," you know, maybe something… [laughs]

Jo Reed: You know, there are certain tropes, like a haunted house or a house filled with props from horror movies and dark eerie forests--these appear repeatedly in horror. Why do you think these elements remain so enduring and effective across stories, genres, generations?

Christina Henry: I think part of it is that we're always grappling with grief and death, and that the idea that spaces, that places, that objects, may, you know, that there may be ghosts or that there may be forces from beyond that are trying to speak to us. I think that it's such an innately human thing to want to know what else is beyond this mortal coil? What else is out there? And those stories are attractive, whether the being in the story is for good or ill there, right? I think that it's like, oh, well, there's proof. There's proof that there's something else out there. There's proof that when I die, I might be able to speak to my loved one, or that my favorite aunt who passed away can come back and communicate with me. I think that there's this longing to know that there's something larger than ourselves. And I think that a lot of horror, things like haunted houses and ghost stories, they're grappling with that. They're grappling with a very human fear of what if I die and there's nothing else out there? What if I just die and then that's it? And I think that horror always is, obviously, it's only effective because it's so psychological, it's so emotional. But horror is always kind of going for that core of you, it's going for that part of you that's most vulnerable, and that's where the stories are effective.

Jo Reed: Right, because isolation works so well in horror. You incorporate that into your books. What are what are some of your favorite horror tropes to work with as a writer?

Christina Henry: You know, I had this ongoing joke that for a long time I was in my Haunted Forests phase. I wrote probably like five or six books where key elements of action were taking place in forests. I think that's because I grew up in upstate New York, and I was in the Hudson Valley, there were a lot of forests around me, I spent a lot of time in the forest as a kid. And I think that there's wildness there, and a sense that you're away from civilization and you can't control things. And that is something that I've always loved exploring and playing with. And my more recent books, I say, I'm now entering my "Haunted Buildings" phase where things are becoming a little more urban, and I think that is just the sense that I have, you know, that every place you go can be haunted.

Jo Reed: Yeah, I just got scared. Okay. It's the way you said it. Are there any tropes that you intentionally avoid?

Christina Henry: I think that I've had a couple of books that are a little gorier, but I don't think I go full out splatter for most of my books. And I think part of it is that I'm always interested in, like I said, in character, so that everything that happens in a book is filtered through some character's perspective. I also find that I don't necessarily need to describe things super explicitly all the time, because I think that readers do a lot of the work themselves. I think that people sort of imagine as much or as little as they're comfortable with, but I wouldn't say necessarily avoid tropes. Maybe I just haven't gotten to them yet.

Jo Reed: You know, so many readers love the predictability in horror and others enjoy kind of when what we think of as tropes are subverted, so how do you strike the balance playing with audience expectations on one hand, and yet surprising them with something new.

Christina Henry: Yeah, I think there's always that risk in any kind of genre fiction, right? I mean, every genre has its own tropes and mysteries, you certainly expect the crime to be solved at the end, right. In romance, you expect there to be a happily ever after. I mean, I think every genre has its own tropes and its own expectations that come into the genre. Years ago, I read a book and now I've forgotten the author's name. I think it was Derek Thompson, he was an editor at The Atlantic. And it was about how things become bestsellers. I remember a line in the book where he said that “audiences want the familiar with a gentle touch of surprise. So they want you to give them what they're expecting, what they went into the book wanting, but they want a little bit of a surprise.” So, they want your twist on it, they want your edge.

Jo Reed: Do you think horror thrives in moments of societal uncertainty like the pandemic?

Christina Henry: Yes, absolutely. I think that horror is going through a real golden age right now, not just in books, but in film. I think that there's been a real rediscovery of horror, and I think that when horror fans look back on horror, they think of the 70s and the 80s as a real golden age, when there was a lot of innovation, and there was a lot of different kinds of films that were coming out, different kinds of books that were becoming popular. Obviously Stephen King. John Saul, I remember seeing a lot of John Saul covers when I was a kid. Clive Barker. And if you think of all the upheaval that we were going through during that period, and now, again, all the upheaval we've been going through for about the last 10 years, I would say. I think that people have so much anxiety, and I think that you want to put it somewhere. And again, that's where horror can be a real release. It can take your anxiety, it can express some of that anxiety metaphorically on screen or on the page, and it can also help us process some of that emotion, process some of the feelings that we're feeling, and provide a little bit of a release of that.

Jo Reed: How did you come to writing?

Christina Henry: Oh, I've wanted to be a writer since I was 12. I read The Lord of the Rings. Like a lot of kids, I actually came to horror sort of sideways from fantasy. And I just loved that book so much, I loved everything about it. I loved the creation of the world. I just wanted to live in it. And I asked my dad for a notebook, and then I started writing my first book right there, when I was 12. It was not good. And I just always wanted to be a writer ever since then. I think it was natural, I was a kid who read a lot, I was a kid who did a lot of make-believe. When I played games, I made up stories, so I think it was just a natural extension of the way my brain was already working.

Jo Reed: When you sit down now to write a new novel, do you outline the story or do you prefer to let the plot develop more organically as you go?

Christina Henry: So we were talking earlier about the roller coaster, right? So my favorite way to write is to start that roller coaster without the tracks, just see where it goes. I never, ever outline. Because I want to discover the story the same way the reader discovers the story. I discover it as I'm writing. So I write by hand, and I write chronologically. And writing by hand, I think, really makes you slow down a little bit, just makes you be a little bit more thoughtful because your hand can only go so fast. And every 50 pages or so, I type it into the final manuscript, and I kind of edit it as I go, which does help the first typed manuscript be pretty clean overall. But I love the process of finding the story as I'm writing it.

Jo Reed: And horror often relies, not often, it does, it relies on pacing, it relies on atmosphere to build tension. How do you approach crafting those elements in your writing?

Christina Henry: So usually as I'm typing it out. So, I just finished writing my 19th book, and I will say, like anything else, if you practice, you get better. You can start to see where things are a little saggy, maybe you need something else here, something hasn't happened in a while, you need to punch up the tension. Or maybe you just need more information at this point. That's the editing process. I do try, before I hand in my final draft, to go through the manuscript and say, what would my editor ask? I try to anticipate her questions. As if I'm looking at it from the outside. And that helps with things like pacing and stuff like that. But I would say, as a rule of thumb for my own writing, I try to have something happen every chapter, either major character development or major plot development, something should happen every chapter. The chapter shouldn't just be sitting there where everything is static.

Jo Reed: Your reimaginings of classic tales like Alice or Peter Pan—your book, Lost Boy, or The Girl in Red, another one, Red Riding Hood. I mean, they're a hallmark in some ways of your career. How do you choose which stories to retell? And as part of that, what excites you about reinventing familiar narratives and characters?

Christina Henry: You know, I never intended to like become known for that, it sort of just happened that there were some things that interested me at the time. And that's how it is sort of with all of my books, that like some character appears in my head and then I want to know something about them. So, as an example with The Girl in Red, I saw Red, the main character standing by a fire, wearing a red hood, holding an axe. And I was like, "Who's that girl? I need to find out." So I had to write a book so I could find out who she was. When I wrote Lost Boy, the motivation for that was a little bit more personal. My son, when he was five, went through a very intense Peter Pan phase. He wanted to dress up as Peter Pan, he wanted to have the window open so Peter Pan would come and get him, take him to Neverland. He wanted to watch movies about Peter Pan all the time. So I was watching the Disney Peter Pan with him for, you know, approximately the 250th time, and I said to myself, "Why does Captain Hook hate Peter Pan so much?" And then I had to write a book so I could find out. This is pretty much my process, there's a character, there's a question, and then I have to write the book so I can find the answer.

Jo Reed: We are very close to Halloween, and I really want to touch on your book Horseman, which revisits the legend of Sleepy Hollow, but of course with your own unique twists. What drew you to retelling that particular story?

Christina Henry: That was, at least partially, because of my dad. My dad always told me the Washington Irving stories when I was growing up. We watched the cartoon of Sleepy Hollow every Halloween. And I grew up in the Hudson Valley, which is very close to where the story takes place. It's just part of the fabric of my childhood. And I was just drawn to the idea of telling a kind of sequel. It's my own-- it's pretty much a sequel to Sleepy Hollow, find out what happens after the last line of the story.

Jo Reed: Well, Ben, who's the protagonist of Horseman, grapples with identity and family history. In addition to the horror, the scary stuff. He's a trans boy living at a time when the divide between genders was so rigid, and a lot of his struggle in the narrative centers on his fight against really systems of oppression. And it's organic to the story, I don't feel like you're standing on a soapbox. It really is just so enmeshed in the story. Tell me how you decided to weave these personal struggles into this gothic supernatural setting.

Christina Henry: I think Ben just came to me that way. He was just there and that was who he was. And I always think to some degree we're impacted by things around us, things that we're hearing, seeing, and there was so much anti-trans rhetoric at the time. And I didn't want to be presumptuous in writing a trans character. I'm not a trans person. But I wanted to, I think, to show trans people that they were loved, they could be heroic. I think it was just so upsetting to me on a personal level to sort of see this rhetoric. And I wanted people maybe who never thought about trans people to see a character in what you might call a safe setting, right? In a story. And maybe that would help to some degree to understand. But I don't claim in any way to speak for trans people, I just wanted to write something that showed trans people in a heroic role. But Ben just came to me that way..

Jo Reed: What do you think it is about the Headless Horseman story that still resonates with readers today?

Christina Henry: It's such a perfect ghost story, and this figure, a cloaked figure riding through the night on the horse, I mean just the visual of it is so powerful and the idea that he'd be searching for a head, and it might be yours that he's going to take. Of course, in the story, in the original story, it's very clear that it's Brom Bones who's actually play acting as the Headless Horseman because at the end of the story, Washington Irving says that… I can't remember the exact line, but something to the effect of that "Brom always laughed whenever people told the story of the Headless Horseman," because it was just his way of running Ichabod out of town. He was trying to get rid of his rival. But I think that the imagery of the story is so powerful that people really gravitate to it, and there's so many ways to tell that story. You can play it as it's real, you can play it as not.

Jo Reed: Do you know, as a fan of both horror movies and literature, do you find your approach to writing is more influenced by films or by books? Or both?

Christina Henry: I think it's probably both. I think that it's very, very difficult to write a book now without being-- or a film for that matter, without being aware of what's come before you. I think to a certain extent, you do feel a need to acknowledge the tropes within your own genre, but I think that the thing that I'm always a little leery of when I'm writing is that I don't want my writing to sound like anyone else's. I read pretty widely. I read not just horror, I read a lot of mystery, I read a lot of nonfiction, and I try to make sure that I'm not sort of locked into one kind of thought process when I'm writing, because I always want to make sure that my writing sounds like myself.

Jo Reed: You know, Halloween is often associated with spooky things.Do you have personal that you like to read or watch during Halloween?

Christina Henry: Yes. Again, part of this was my dad growing up, my dad always watched the Sleepy Hollow cartoon. We have to watch it every Halloween. And I always watched "It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown." Which is, again, sort of a family tradition. And then I usually pick a couple of my favorites. I watch the original John Carpenter “Halloween” every year. I like the Tim Burton Sleepy Hollow, and then whatever else sort of takes my mood, I think, on that day.

Jo Reed: Okay. So looking ahead….What themes or ideas are you excited to explore in future books?

Christina Henry: So I just finished writing a book that for now is called The Place Where They Buried Your Heart. I say "for now," because in publishing your title can change at any time. And that is a book, again, about a house, but it's a house where a terrible tragedy has occurred, and the tragedies sort of start to reaching out for the people in the neighborhood, the people around it. I do think, as I said, I'm in my "haunted buildings phase." I'm very suddenly very interested in places, in structures. So we'll see how long this lasts.

Jo Reed: Oh, Christina Henry, thank you so much. It was really a pleasure to talk to you, and I appreciate you giving me your time.

Christina Henry: Oh, thank you. This was a great conversation.

Jo Reed: That was author Christina Henry. Her most recent book is The House That Horror Built. You’ve been listening to Art Works, produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. If you like the podcast, follow us and leave us a rating. I’m Josephine Reed, thanks for listening.

In time for Halloween—a conversation with author Christina Henry, who has written 19 books of horror. We discuss her latest book—The House That Horror Built, a chilling story set during the pandemic. The novel follows Harry, a single mother navigating the struggles of parenthood and financial instability, as she takes a job working for a reclusive horror film director. Henry talks about the story’s atmospheric tension, its exploration of parenthood during the pandemic, and the enduring appeal of classic horror tropes.

Henry discusses her creative process, including her love for horror films and how classics from the Vincent Price and Boris Karloff era inspired the novel’s atmospheric tension. She explores the enduring appeal of horror tropes such as haunted houses, eerie atmospheres, and mysterious characters, examining why these elements remain effective across generations. She also discusses why people are drawn to horror, how it provides a controlled thrill, and how moments of societal upheaval, like the pandemic, fuel the genre’s resurgence. Finally, Henry shares insights into her writing approach and finding the balance between character-driven narratives and the tension that horror demands.

Let us know what you think about Art Works—email us at artworkspod@arts.gov. And follow us on Apple Podcasts.