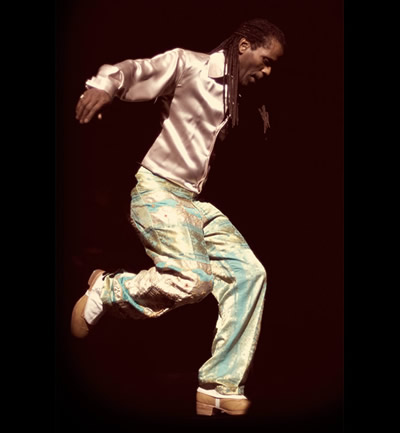

Reginald “Reggio the Hoofer” McLaughlin

Photo courtesy of Reggio McLaughlin

Music Credit: “NY” composed and performed by Kosta T from the cd Soul Sand, used courtesy of the Free Music Archive.

(music up)

Jo Reed: Welcome to Art Works the weekly podcast from The National Endowment for the Arts, I’m Josephine Reed.

You’re listening to the tap dancing of 2021 National Heritage Fellow Reginald Reggio “The Hoofer” McLaughlin.

(sound of tap dancing)

For more than half a century Reggio McLaughlin has been the embodiment of joyous dance as he tapped on Chicago stages and streets and through classrooms and festivals. His distinctive tapping, historical knowledge and ebullient personality has given him a well-deserved reputation as a passionate performer and dedicated teacher who has kept this dance tradition alive and thriving.

Reggio is also a great storyteller, so I’m going keep this short and just mention a few of his highlights. He began as an R&B musician, and then he was mentored by the great tap-dancer Jimmy Payne—which gave him a solid foundation in dance and great respect for tradition. Making his own opportunities, he was a busker in Chicago’s subways until he came to the attention of Urban Gateways—a non-profit that brought the arts to underserved children.

In 1994, he met Ernest “Brownie” Brown, a legendary dancer who had performed on Broadway with Duke Ellington and Count Basie and was one of the co-founders of the extraordinary dance ensemble the Copasetics. Brownie and Reggio teamed up and danced together for nearly two decades. Twenty-seven years ago, Reggio began teaching tap at the Old Town School of Folk Music where he’s still an in-demand teacher. He’s performed around the world and throughout the country. But for Reggio, it all begins and ends in his hometown of Chicago.

Reginald McLaughlin: I always say I’m pure Chicago, born in Chicago, raised in Chicago. Even though I had opportunities to probably move to other cities and especially New York because that was kind of like a real tap mecca, but I always stayed here in Chicago. I always felt like Chicago was good to me and I’m just proud of being Chicagoan and I wanted to be a good example and a light for other youths coming up here in Chicago and let them know, hey, look, I started out performing in the subways and in streets in Chicago and if I can do it I believe that you can do it, too.

Jo Reed: When did you fall in love with tap dancing, Reggio?

Reginald McLaughlin: When I was a kid probably around 7 years old. In Chicago they had what we call a park districts was a community center. They had a lot of after school programs and at that time that’s where my mother would send us and my older sister and them would be taking tap because they offered that mainly for the girls and then there was a divider in the gym and the boys did more gymnastic stuff like that and at the end of the program they have a showcase where they invite the parents to come see what the kids learn and you invite your friends and everybody and when I saw tap I just fell in love with the rhythm, the sound, the movement and it was love at first sight. At that moment it just stuck with me in my heart and my soul for life.

Jo Reed: But you didn’t start tap lessons then, did you?

Reginald McLaughlin: No. I couldn’t; I had a large family, eight of us. Your mother is just trying to make it day by day and survive and so I would ask my sisters “Hey, show me the step. Show me the step,” and you go out on the sidewalk and put some bottle tops on my gym shoes and try to get that sound and I worked with some homemade tap shoes that way because I never really had the opportunity like formal training where you would go to a school or some type of dance academy to learn and that’s how I began from that point and as I got older and then that’s when I was introduced to veteran hoofers, veteran Broadway vaudeville hoofers later on.

Jo Reed: You had a whole other and very successful career as an R&B bassist when you were a kid. How did this happen?

Reginald McLaughlin: Oh. So my father used to play guitar around the house. My older brother, he got my father to show him some chords and teach him how to play guitar and I admired my big brother like oh, man, can I hang with you? Can I hang with you? Nah, man. You can’t hang with me you’re too little and all of that stuff. So one day he say “Look, Reggio.” He say “Why don’t you learn how to play bass and once you learn how to play bass we could start a band together,” and I felt like ah, yeah. That’s so great. This is my opportunity to hang with my big brother. So he started to teach me how to play bass when I was around 12 years old and then long story short there’s a record company in Chicago. It was called Brunswick Records. Brunswick Records were the rhythm and blues sound of Chicago the way Motown Records in Detroit was the Motown sound. So my brother, one of his mentors got him a job at Brunswick Records and he was getting ready to go out of town with one of the recording artists there and the bass player got sick and he said “Look, my little brother know how to play bass. I could teach him all the songs and everything tonight and he could go with us,” and they had no other choice. So they say “Okay. Good,” and so he asked my mother. My mother agreed because we lived on the South Side. We lived in a very tough neighborhood and she felt like this was a way that would get me out of this tough neighborhood and I went. Anyway they were so impressed with my playing that they kept me on with the recording company, but it gave me an ultimatum. Yeah, man. Either you can go to school, which I was about in my sophomore year or you could stay with the company. I chose to stay with the company because of the circumstances at the time of being able to get off that neighborhood, out of that neighborhood and Brunswick Records they had people like Jackie Wilson, the Chi-Lites, Tyrone Davis, Lost Generation. So they had a number of top notched artists. So I fell into that because I wanted to hang with my brother, but you know what was so funny. I still always wanted to tap. <laughs> I always wanted to tap, but yeah. So I did that and I’m very glad because that experience that I got from being around a record company now allows me to write my own music and songs. With my tap dancing now I do a lot of shows with live musicians. So I’m able to tell them what I want and the intro, how long I want it to be and my future endeavors that I’m working on a one man show and I’m writing all original music from and so I think destiny had just a way of taking you down a whole lot of different avenues and now I’m putting them all together for a masterpiece.

Jo Reed: I bet. How long do you do that?

Reginald McLaughlin: Oh. I did that for a while. So I was 15. I could have did it till my early 20s and what really happened was at that time all the clubs had live music. So when you wasn’t traveling on the road you could play in some of the bars and stuff at night. I was playing, believe it or not, back then you could play in the bars at a young age, but you just wasn’t allowed to drink or anything like that. So I was playing in the clubs at 15 years old in Chicago.

Jo Reed: How did you transition from playing to tap?

Reginald McLaughlin: What happened was “Saturday Night Fever” came out with the disco music and everything and when they did that all the clubs started getting disco DJs in and everything and they weren’t hiring the live bands <laughs> no more. So when things transitioned and the live music was being evaporated in the clubs I felt like this was a great opportunity for me to pursue what I always wanted to do, tap dan [sic], and by me playing the music it gave me the money that I need to train with these veteran dancers.

Jo Reed: And one of the veteran dancers who taught you was Jimmy Payne.

Reginald McLaughlin: Jimmy Payne. Right. Okay. So he taught in here in Chicago at a time at his studio, 218 South Wabash. That was like a artsy building and I went to Jimmy and he started teaching me, but see at the time that I started working with him tap was a outdated dance that nobody didn’t do anymore. So people kind of thought like man, this guy nuts. You want to learn how tap. Nobody does that anymore and not only that they didn’t understand why I wanted tap when I was like one of the top 10 bass players in Chicago, but it never went away. I wanted to tap, I wanted to tap and all during that time that I playing bass I was still dabbling with my tap here and there and here and there, but then finally when I got with Jimmy that’s when it really transitioned to become my main priority.

Jo Reed: As you said tap dancing was considered outdated and there weren’t gigs. So you began dancing in the subways in Chicago.

Reginald McLaughlin: Correct-- because you had to make your own opportunity if you wanted to tap and that’s what I wanted to do. I had offers for jobs and things and I was like no, no. So I would go down there and tap dance. If you asked people can you borrow a little money? No, cut your hair, <laughs> get a real job. So ah, man. I went through all kind of obstacles of people trying to deter me and change me for not tapping, but I stood my ground, man, and I let that happen. Everybody was change you, try to change you. If meet a young lady, you meet her parents, they ask you oh, so what do you do? Oh, I’m a tap dancer. The parents look at you, tap dancer? That ain’t no job. That’s like a hobby or a recreation. I like no, not with me. I was proud of it and I stood up. But after that you’ll be kind of it was just like hey, little daughter. <laughs> I think you need somebody going to the university or college to be a doctor or lawyer or something. A tap dancer. So I went through a lot to go all the way with this. I was getting hit all kind of ways of different obstacles coming at me, but I didn’t let that stop me though. I really, really paid the dues down there and in the subway was rough.

Jo Reed: I was going to say it’s not for the faint hearted.

Reginald McLaughlin: No. You can’t be weak down there. Look, sometimes I had to wake up an hour or two to condition my mind to go down there. It wasn’t like here you got a paid audience and you had all kind of people down there in the subway. Some of the teenagers they made fun of you. Oh, man. Look at that. Ha, ha, ha, ha. Man, my uncle could do that and dah, dah, dah, dah and so you had to deal with that.

Jo Reed: I think that tapdancing in the subway would really really help to figure out very quickly what people liked and how to connect with the people.

Reginald McLaughlin: Oh, that’s where it all begin. That’s where my whole stage persona come from down there and I loved it because I developed an intimate relationship with people and I bring that to the stage. Because you right there on the same level of the people, toe to toe and “hey, how you doing, hoofer? Man, I ain’t got nothing to give you today, but I get paid Friday if you’re down here I’ll toss you a little something.” And you discover what steps and combination the people like when they clap. Yay! That’s it. You write that down. Okay. I got to keep that over the top. They really like that one and it makes you work. Them people down there they clap. “All right. Get it, brother. Go ahead. Oh, man.” And root you on and what not like that, but my whole stage persona came from in the subway and being with people and even now when I perform on stage if I had a choice I do a lot of school performances and they say “Do you want to be on the stage or do you want to be on the floor?” All the time. I just want to be on the floor where I could talk with people and I have a lot of audience participation and student participation. I’m able to get them right up and dance with me and the people when it’s like that they become more a part of your performance than just being a spectator.

Jo Reed: You began working with Urban Gateways.

Reginald McLaughlin: Yes. I did. That was the beginning of my rise was with Urban Gateway.

Jo Reed: Explain what they do and how you got together and what you did for them.

Reginald McLaughlin: Okay. Urban Gateway that’s where I learned the format of art in the form of education and what they do they prepare different genres of art to perform in the educational system like schools, libraries, museums. So their tap act at the time left their institution. So one of the program directors would always see me and myself and another dancer down there performing. So when they left she came down there and got us and said “Okay. I would like for you guys to come and meet me at Urban Gateway. We’re interested in putting you guys a program together to perform in the schools.” So we met with her and the name of the program was called “Taps and Tuxedos” and actually what they do they write out your whole program that you’re going to do in the school. It’s a scripted program and let you know you stick to the script. Everything is very well structured. So we came and they work with us and we had to run our program over and over until it reached satisfactory to their standard and once it reached that then they have a showcase and they invite all the schools to come and on a retreat, a weekend retreat, and then they present all the new artists that they going to present for that following year and then they see you and hey, we love it and start booking you, man, and I was hot. Five years we was just everywhere, everywhere.

Jo Reed: And did you like working in schools?

Reginald McLaughlin: I loved it working in school. I loved everywhere I perform and dance at because it gave me more knowledge to go with the knowledge that I have as a dancer because if I go into the school you weren’t able to just go in there with pure entertainment. There had to be a educational part to that. So we’ll talk about the origin and history of tap. Sometimes I would go to other like high schools and stuff and I would have to adapt a program to fit in with more like the renaissance, Harlem Renaissance era, and make it a part of a history class. So I always had to adjust what I do to adapt to different formats.

Jo Reed: Now you met the great tap dancer Ernest Brown and he became your mentor. How did you hook up with him?

Reginald McLaughlin: What happened was I went to school with a young lady named Frances and she kept telling me her grandfather was a tap dancer and the next time he coming to town she’d introduce me to him and and she introduced me to him and eventually shortly after that he moved back to Chicago and I would go over there, visit and stay with him and he start working with me teaching me a lot of the very authentic traditional styles of tap dancing. And he turned out to be one of the cofounding members of a very elite tap company at the time called the Copasetics and the Copasetics, they established them self in 1949 after the passing of Bill “Bojangles” Robinson who taught Shirley Temple how to dance. And when I came over there and I would always ask him show me this, show me that and he would and then later on we end up choreographing a little tap for a musical at that time called “Tommy Parker Black Minstrel Show” because they didn’t have a choreographer and one of the actors asked would I give him a few moves to go with a monologue he was doing and when I found out they didn’t have nobody choreographing for them because they wanted to do a cake walk from back in that era. I said “Well, look. Since you all don’t have a choreographer, my mentor he knows how to teach you a cake walk and all of that,” and so anyway the brought us on board and one of the critics wrote about us choreographing this show and everything snowballed from there.

Jo Reed: And you learned a lot of tap history from Ernest Brown.

Reginald McLaughlin: Brown. Yeah. First hand because he would see something and he’d say “You know what, Reggio?” He say “You see that what they’re saying right there in this book or this and that.” He’d say “That’s not true.” He’d say “That’s from the author’s point of view,” he said “because I was actually there when this happened or that happened,” but one of the greatest things that he taught me that I liked he told me when we used to go perform he’d say “You know what, Reg?” He’d say “All the dancers, most of the dancers today are too spoiled.” He’d say “You go to a theater, oh, I can’t dance on that floor. This floor is this. That floor is that. Oh, it’s too shiny. Oh, it’s this.” He’d say “Man, when we was back in the day whatever the condition of the floor was that’s what you danced on if you wanted to work. It was non-negotiable. That’s the floor and that’s what you had to dance on.” So he really kept me so down to earth and so humble because coming out of the era that he came in he showed me a much more better appreciation for the art itself.

Jo Reed: I want you to share a little bit of the history of tap, its origins, how far back you can trace it.

Reginald McLaughlin: You know what? You get these different theories and stuff, but I’m going to tell you purely the way how it was told and then introduced to me.I was always told when the Africans were brought to America, they were prohibited from playing the drum. They began to substitute that with their feet and used their feet to beat out and tap out certain rhythms and things in place of the talking drums and that developed into a art form on the plantations and that’s the way it was always brought to me and that’s the way I accept it because I understood that and then when you see when they brought tap to the stage.

Jo Reed: It’s such an American art form.

Reginald McLaughlin: It’s totally an American art form and it came with musical theater right from the beginning when they presented it on stage. It came right there as a art form that developed here in America and continued to develop coming out of minstrel shows up into vaudeville and then Hollywood. The Hollywood is what put the glamour into the tap with the marble floors and the tuxedos and now you got all these fabulous musical. So it was an art form, yeah, that developed here and is accepted and it’s funny. I taught workshops all over the world and especially with Brownie legacy people came from all over the world to study tap here in America and it was good because Brownie passed a lot authentic traditional styles of tap and dance and especially routines that they did and that were created and develop here in America. Yes.

Jo Reed: I want you to describe the chair dance because that’s one of them.

Reginald McLaughlin: Oh, my God. Okay. When I got with Urban Gateway because it was art in the form of education I would go to the library and try to pull up whatever tap tapes that I can ever find that they had and the Copasetics, five members of them, they did “The Dick Cavett Show” and one of the dance I saw them do was the chair dance. Oh, my God. Out of all the complicated or complex dances I do the chair dance is my number one favorite all hands down.

Jo Reed: It’s a very complicated tap dance that’s performed when you’re sitting down.

Reginald McLaughlin: Yes.

Jo Reed: Did the Copasetics invent the chair dance.

Reginald McLaughlin: Yes. So the Copasetics created this chair dance, man, and that’s a beautiful classic and Brownie showed me the dance and I’ve been doing it and carrying on that legacy from then all the way into this very day and I get people always calling teach me the chair dance. Can you do a workshop? We want to learn the chair dance.

Jo Reed: How long did you dance with Ernest Brown?

Reginald McLaughlin: About 18 years until he was almost 92. We danced all of the way to the good, to the very last drop until we had to go in a nursing home. But we danced all the way until then and one of the things that we did as a new generation of tap dancers, we turned back the hands of time, and we honored the forefathers that were still around because we felt like they didn’t get the credit that they justly were supposed to get when they were around. Because they was back during a lot of Jim Crow days. So, that was our way of paying honor and tribute to them. So, I kept them with me from then on.

Jo Reed: Well, in the mid-’90s you began teaching at the Old Town School of Folk Music.

Reginald McLaughlin: Yes.

Jo Reed: And you’re still there.

Reginald McLaughlin: 27 years. Man, I put all of that tap a lot of stuff out and I only had two or three dance teachers at the time and yes, I’d stay there. It’s so funny when all of the things that I did I didn’t plan anything. It’s almost like by just dancing and destiny took me down a path that continued to develop and escalate into different aspects of my art form to producing shows. I produce two annual shows. My holiday show, “The Nut Tapper,” was based on “The Nutcracker,” ballet but I do a hip variation of that, and then a national tap day which is honored into law in 1989 as a true American folk dance. I honored that by doing a national tap day performance as well.

Jo Reed: And that’s Bill Robinson’s birthday.

Reginald McLaughlin: That’s Bill Robinson’s birthday.

Jo Reed: National Tap Day.

Reginald McLaughlin: Yes, they made it on May 25th on his birthday.

Jo Reed: You’re not just teaching tap. You’re giving students a history or your audience. It’s a history of tap.

Reginald McLaughlin: You have to.

Jo Reed: It’s a social context as you teach.

Reginald McLaughlin: Yes, you have to because when you get a history now, they understand and they understand and they connect with you so much better when they understand the history. You as a Bonafide- dancer you understand that at the same time you’re entertaining and performing but you’re also on a mission of sharing the knowledge that you know and the educational aspects of what you’re doing, and how to dance. It's been created and developed as American folk dance but when you say America to me, America means all. A-L-L, all because you have all kind of Americans here. I always just felt like somebody has to keep the traditional American tap alive, and I felt like that was part of what I wanted to do as well.

Jo Reed: As you said, you do two shows a year for the Old Town School.

Reginald McLaughlin: Yes, those are the ones that I produce and I incorporate all of my students that I teach and they love that.

Jo Reed: I want you to tell me a little bit about “The Nut Tapper,” because that show’s been going on for what?

Reginald McLaughlin: About 20, 21 years. <chuckles> I never had no idea that it would go on that long. I thought I would do it one time. After I did a show, my first show at Old Town in the ‘90s, it was called “The History of Tap,” and I kind of mixed it all up, and then I was approached. “Man, you should do a holiday show around Christmas show.” Oh, okay, what should I do? Okay, well, all the ballet dancers do that “Nutcracker.” “The Nutcracker.” So, I say, “Maybe you should do the Nut Tapper or that,” and then I’m doing “The Nut Tapper.” So, at that point, I’ve never saw the "The Nutcracker" ballet <chuckles> and I don’t understand it. So, I went to the library and got videotapes on “The Nutcracker.” I’ve watched the show then I went to some ballet performances of it, and what happened when I was watching the ballet, you could not follow what was going on. Even though they’re telling the story through the dance, it was hard to follow the story through the dance if you didn’t already know what the story was, and I was like, “Wow, that’s puzzling.” So, I decided okay when I did my show, I’m going to get me a real hip, talk-that-talk, walk-that-walk narrator. So, I got me <laughs> one of these Def Jam poet kind of guy and he’s going to narrate the show, and I wrote out, and my show it’s really a show that really-- We talk about take place in Chicago. Instead in a party scene, I decided we’re having a tap jam at the party scene. So, I spiced everything up and then in my presentation is where I could always switch and bring different guest artists. So, that’s when I would incorporate other percussive dance styles like Flamenco because I studied that, and Mexican Zapateado. Sometime I could put in any variety of dance. So, I bring in different cultural styles of dance. Sometime I bring in an Indian dance. I could bring in just different dance. So, at the same time, it’s a very multicultural style of the dance and then my “Nut Tapper” guy was like, “Man, he got locks in his hair.” <laughs and claps> Yes, they made me a little doll like me with locks in his hair so that I could wear locks.

Jo Reed: That’s great.

Reginald McLaughlin: Yes, it’s fun. You laugh in that show. It’s a lot of fun. So, 21 years, man, and they not having let me stop, and they already calling me now at Old Town for the field trip for November.

Jo Reed: I was going to ask you about that, Reginald, because obviously it’s been a pandemic year.

Reginald McLaughlin: Yes.

Jo Reed: What have you been able to do in terms of teaching and performing during the pan--

Reginald McLaughlin: Zoom, Zoom, Zoom, Zoom, Zoom, Zoom, Zoom. <laughs> Yes, at the--

Jo Reed: Some of us are old enough to remember that. <laughs>

Reginald McLaughlin: Yes, <laughs> oh you know what I’m talking about.

Jo Reed: I know exactly what you’re talking about.

Reginald McLaughlin: Yes, so they got the school -- It took them a minute or two but they set up. We have a cart with computer and everything set up, and I was teaching a limited amount of Zoom classes over the computer.

Jo Reed: And are you beginning to teach in person again?

Reginald McLaughlin: September, I’m already scheduled and the classes are filling up like, “Yay.” It was so touching because we’ve been out over a year. And here are all the people and my student would say, “Oh, I’m so happy. Oh, I missed the tap. Oh, and this.” It was just so touching in how they all missed each other and became like a family being in classes for five, six years and more, and they were just so happy, and it would just make you realize how much they were affected by not being able to dance and missing one another, and it made you realize how all of this it became a regular routine of their life.

Jo Reed: You’ve been a part of the Old Town School’s international program quite a few times.

Reginald McLaughlin: Oh, yes.

Jo Reed: Tapping your way to Europe, and India, and South America.

Reginald McLaughlin: Oh my God that Indian trip. It was a 24-hour plane ride from Chicago non-stop to India. I was up in the air 24 hours. Imagine seeing the sun go up, go down, and then come back up again. <chuckles>.

Jo Reed: How did audiences react to and respond to this really American art form?

Reginald McLaughlin: Let me tell you something. Oh, oh, oh. <laughs> The one thing that first is that the dance is a universal language. Whether you spoke the language or not they can feel that heartbeat in that dance. They love it because they do a foot stomping dance called Kathak, if I’m not pronouncing it incorrect, and oh my God. But they do it barefooted. But when they hear the tap sound, and not only that I did a fusion with an Indian dancer while we was there who did the Kathak and I did the tap dancing. Oh my, God. I think they just loved that. Oh, I never been to anywhere in any country that did not like tap dance. They love the musicals that came from America with tap in them and then the amazing thing about it is you go to these places and I’m going to tell you 95 percent of people have never seen it done live, and that’s what really wipes them out, man, and then you get to dancing, and they calling you over, they want to see the bottom of your shoe, they want to try them on, and <chuckles> all of that stuff. And everybody is amazed with it, you know what I mean? Especially when you see you’re just using your body that way, and beating out these rhythms, and “Man, how do you do that?” And then it was just so cool. I would do my art form and the Indian dancer would do hers, and then we’d do something together. That was the beauty. It just kind of brought that unity and that art brought us all together.

Jo Reed: Yes, a tap dance is so joyous.

Reginald McLaughlin: Yes, it’s a happy dance, you know?

Jo Reed: It is a happy dance. It really is.

Reginald McLaughlin: Yes, man. Yes, it makes people happy and fun and especially one of the things I love doing is just go get somebody out of the audience and bring them up to dance with me. Oh, do they love that and the kids love that, and, so it creates a very beautiful environment for you, you know?

Jo Reed: If you think of your legacy, Reggio, what would you like it to be?

Reginald McLaughlin: I would like it to be make people feel like -- There was a saying that they say in the neighborhood. If you’re true to it, it will be true to you, and that’s what I want people to feel like. If you really believe in what you’re doing, you love it, and it’s something that’s very pure and wholesome, that you can do it. You will be all right. It will be all right for you. Be prepared for all of the obstacles that are going to come and get in their way from every form and fashion, and that they have to be strong enough to overcome those, and don’t let it deter them from maintaining that path and keep on going. I’ve seen what I did in my art form made a mark and making people happy. I’ve taught hundreds, and hundreds, and hundreds of people, and when you get these feedbacks of how happy it made them, and it just brought some kind of joy in their life, and make their life a little more worth living for, then that’s what I would look for. Just to continue to get that kind of feedback from people.

Jo Reed: You’ve won many awards. Many, many awards. Too many to list and now you’ve been named an NEA National Heritage Fellow. Tell me what that means to you.

Reginald McLaughlin: What can come up against a national endowment fellowship award? The highest award of the nation. You know what I’m saying? I’m living in heaven and glory days every day that I think about that. I wake up in the middle of the night and just, “Thank you, thank you, thank you, thank you,” because it’s like I did a lot of things, and I’ve worked very hard. You go through the test of time. You stick to the path and everything, and sometime I never felt like people were even paying attention to all of that hardship and the trials and tribulations that you have to go through to get to that point. A lot of people don’t know and I’d never let-- There you are. Bring out the violins because I got a story to tell <laughs>. I never do that but also, I really want to say I don’t think I would’ve made it this far as just a solo-- I have my health. I have Sara Godella [ph?] here. I have Jim Barry here. They’re with me, and they listen to me. I have a lot of students. I have Old Town School of Folk Music that believed in what I was doing, and gave me a platform to continue my work and it kind of gives you that motivation that helps you.

Jo Reed: You created a community.

Reginald McLaughlin: I think so <chuckles>. Yes, it feels good when you walk through the neighborhood people are like, “Hey, Nut Tapper. Hey, Nut Tapper,” or, “Reggio, I saw your show. I saw your show.” Some people had that hard to handle when they walk with me. “Oh, you just know everybody. Everybody know you.” Well, what can you say? I’ve been out there all my life.

Jo Reed: Well, Reggio, congratulations. This award is so well-deserved and I just send you my congratulations and all my good wishes across this wire.

Reginald McLaughlin: Thank you, thank you, thank you, thank you.”

Jo Reed: That was tap-dancer and 2021 National Heritage Fellow Reginald “Reggio the Hoofer” McLaughlin. Mark your calendars for November 17 when we will celebrate all the National Heritage Fellows with a documentary film where they will all show us their traditional art forms. It’s free—keep checking arts.gov for more information. Thanks to filmmaker Olivia Merrion for the sound of Reggio tapping.

You’ve been listening to Art Works, produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. I’m Josephine Reed, stay safe and thanks for listening.

Tap Dancer and 2021 National Heritage Fellow Reginald “Reggio the Hoofer” McLaughlin has been motivated by one thing his entire life: his love of tap-dancing. He walked away from a successful R&B career as a bassist to pursue his unlikely dream of making it as a dancer. Born and bred in Chicago, he turned to mentors like Jimmy Payne to teach him the foundations of tap dance which only affirmed his passion for dance. Unable to find a job as a tap dancer, he went down to Chicago’s subways and danced there—learning along the way how to connect to an audience. He was approached by Urban Gateways—a non-profit that brings the arts to underserved children-- and began performing in classrooms. But McLaughlin wasn’t only dancing, he was also teaching the students the history of tap and its social and cultural context. Given his talent, personality, and dedication, Reggio McLaughlin was a natural performer and teacher. He teamed up with the legendry tap-dancer Ernest “Brownie” Brown and the two of them performed together for almost two decades. About 27 years ago, McLaughlin began teaching tap at the [oldtownschool.org]Old Town School of Folk Music where he remains an in-demand teacher. And he’s traveled around the world participating in Old Town’s International Program demonstrating tap and collaborating with dancers from many cultures. Reggio is a great story-teller, and in this podcast we talk about Chicago, his career as an R&B bassist, his love of tap as an American art form, choreographing his Christmas classic “The Nut Tapper,” and dancing-- in the subways, in the classrooms, around the world, and with Ernest Brown. His enthusiasm and easy laughter are contagious!