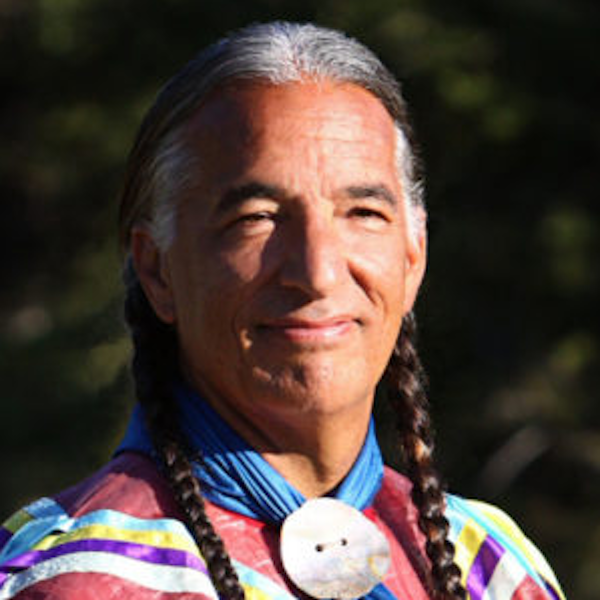

Remembering Kevin Locke

Photo by Adib Roy.

You’re listening to Morning Star performed by the late Kevin Locke

From the National Endowment for the Arts, this is Art Works, I’m Josephine Reed. Today, we’re remembering Lakota flute player, hoop dancer, and 1990 National Heritage Fellow Kevin Locke, who to our great sorrow passed in September.

Kevin Locke spent much of his life learning, preserving, and sharing the traditions of his people. A master flute player, he is acknowledged to have been the pivotal force in the now powerful revival of the indigenous flute tradition which was literally on the brink of extinction. Through Locke’s advocacy efforts, South Dakota state legislature passed a law naming the traditional flute as the state’s official indigenous instrument. Kevin Locke also revived the Sioux hoop dance, another traditional practice that almost died out. The hoop dance is stunning-- in it Kevin uses 28 wooden hoops to create a series of designs and patterns ranging from flowers to orbs. But the hoop dance is not just visual artistry — the hoop represents unity and the dance is an expression “of oneness of humankind.” A born teacher—Kevin Locke brings these Lakota traditions to the classroom— not merely demonstrating the flute and the hoop dance around the country and the world, but actively teaching them to students.

Throughout his life, Locke had been committed to celebrating the traditions of his people, giving presentations throughout the world. Known internationally for his artistry, Locke was determined to use the performance stage to educate the world about the holistic nature of indigenous culture – ranging from linguistics to music, dance, environment, law, and sacred belief. He performed in more than 80 countries, and served as a cultural ambassador for the United States Information Service since 1980.

Kevin Locke was named an NEA Heritage Fellow in 1990, received the prestigious United State Artists Fellowship in 2020, and had performed at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival and the Library of Congress. He also worked tirelessly as an artist-educator in public and tribal schools across South and North Dakota.

I had spoken to Kevin Locke in 2015 when he came to Washington DC for the National Heritage Awards. And reposting the interview again seemed like a fitting way to remember Kevin Locke. Here’s our conversation.

Jo Reed: Kevin, you once said you see yourself more as a teacher than an artist.

Kevin Locke: Yes.

Jo Reed: Talk about that a little bit more.

Kevin Locke: I think that I find that through the folk arts-- I don't really know the dictionary definition of folk arts-- but my understanding is just from having been here at the National Heritage Awards in 1990, was that all of the artists that I met represented tradition that is passed down from generation to generation. And so in the process of going from generation to generation, why then there's a refinement process that occurs in that I think that over time these folk traditions, these folk arts, they tend to accentuate universal themes. And so I find that most of them really showcase the nobility of the human spirit. When I do presentations, I don't think of it at all as entertainment, nothing related to entertainment. It's purely an opportunity to encourage people to, I would say focus on universal themes, like the oneness of humankind, the shared nobility of the human spirit. And I found, just through doing what I do, that it's the perfect opportunity to educate and to communicate these themes to the public. And I think that this is a wonderful way, especially to reach young people. Because you don't have to hit it from an intellectual basis at all. You can just cut to the quick, and you share with them the material. And it just speaks to them in that way.

Jo Reed: I find it very interesting, because I think one thing, among many, that defines folk art is its distinctiveness. And yet, it's really through that distinctiveness that you can come to the universality you're talking about. Whereas, speaking broadly with popular or mass culture, it's really all about sameness.

Kevin Locke: Oh, yeah. Of course, there's something like six or seven thousand different ethnicities on the planet. So each one of them has very unique ways of expressing themselves through, you know, music, or dance, or whatever it is. But it's just that we all live in this world of color, this world of beauty, world of sound, world of, you know, like growth, and everything. So we all have this natural impulse to create sound, to create movement. And so I think the folk arts, it's really at this universal level. It just expresses the joy of being human, no matter where we are. Arctic, tropics, temperate, wherever we are.

Jo Reed: Well you've performed, given presentations, all around the world. And I'm sure the expression of reception can change depending on where you are-- but you find that people can absolutely relate to what you do. And what you're presenting.

Kevin Locke: Yes. Yeah, I've been to-- I think I've performed, I counted, a little over 80 countries now. Eighty countries. So that's what I find, that no matter… I don't have to really explain much, although it helps in places where language is not a barrier. But people can actually relate to the presentation, because of the universal aspect of it.

Jo Reed: Your mother was an activist.

Kevin Locke: Yeah.

Jo Reed: And she was a MacArthur Fellow.

Kevin Locke: Yes.

Jo Reed: Yet, you had to teach yourself as an adult-- a young adult-- you had to teach yourself Lakota.

Kevin Locke: Yes.

Jo Reed: Why? Why was it not spoken at home?

Kevin Locke: Well, it was just that both my parents only could speak English. So I just grew up from childhood with just English. But then when I got to be about, I'd say, 14 or 15 years of age, then just in the area around where I was living there in South Dakota, then I just thought, "Well, I'm missing out on so much!" I just don't think that the mindset was such at that time, was such that it included this idea of being multi-cultural, or multi-lingual. And I think that the general mindset, especially with the Lakota language, I suppose other tribal languages here in North America, was that it was just something that had to go, had to disappear, had to be marginalized, had to be excluded.

Jo Reed: Well, I was really surprised you taught yourself in the 1970s.

Kevin Locke: Yeah.

Jo Reed: And it was illegal, still, at that point.

Kevin Locke: Yeah, pretty much. You know, everything was so suppressed, and of course, in the federal edicts and laws, everything was, of course, officially banned and outlawed. You know, devotional practices and language, as well.

Jo Reed: When you decided you were going to teach yourself Lakota, how did you go about doing that if your parents didn't speak it? And it was a language that was so actively repressed-- how were you able to learn?

Kevin Locke: Well, in the '70s-- I'd say late '60s, early '70s, then there were a lot of people, you know, who grew up only speaking that. There were so many people who were monolingual, only could speak Lakota, or Dakota language. So it-- even though the government was actively repressing it, they were not totally successful. And so there was still such a high percentage of people that was their only means of communication. So those are the people that I wanted to communicate with. And then my mom's uncle was pretty much monolingual in Lakota, so I would just associate with him. I think we still have something between six- and ten-thousand native speakers of Lakota. So it's a pretty high population, yet.

Jo Reed: And you taught yourself the flute.

Kevin Locke: Yes.

Jo Reed: And from what I understand, the time that you taught yourself, there was, they thought, one other practitioner.

Kevin Locke: Just a few. There were just a few practitioners. I was going to school at the Black Hills State University. Then it was called Black Hills State College in Spearfish. And we went down to Vermillion, University of South Dakota. I believe that was in the fall of '72, 1972. And it was my freshman year in college. And there was a gentleman there who I'd seen before, but never met. He was born in the 1870s. He was like in his upper '90s, at this time, in 1972. But he was still a very healthy, very dynamic-- and he was like one of the main practitioners of that tradition, or the genre of music, the songs originate as vocal compositions, and they're played on the flute. And so he was doing a presentation there at this big conference. And so he finished his presentation, and I waited until everybody left, and I wanted to go over there and see, because he was such an artisan, the way he'd decorate, the way he'd embellish his instruments. They were really works of art, even besides sounding beautiful. And so then I went over there, and I was admiring his work, and then I wanted to get his ear, so I asked him if anybody was playing the flute or doing this. He said, "No! Nobody’s interested in this!" Then I said, "Well, what about your family? Maybe your kids or grandkids?" He said, "No, no, none of them are interested in this at all." And then I just kind of off-handedly, I said, "Oh, that's too bad. Seems like somebody should carry this on." And then he was doing something, he was putting stuff away, and he just put everything down, and he stopped and he was silent for a while, and he looked at me, and he says, "Yes!" He says, "You!" He says, "You can do it! You're the one that should do this."

Jo Reed: What did you do? How did you respond?

Kevin Locke: I just kind of ignored it. I just brushed it aside. And I didn't really say anything, we didn't have any further conversation. But sometime after that, I heard that he had passed away. I was at my mom's place. And, you know, he used to make flutes and he'd sell beautiful flutes, he'd sell them for like $15, $20. Now they're worth thousands of dollars if people can get them. But my mom had a couple of his flutes. So she went back and she-- to her room, and she came back, and she brought one of them out. She handed it to me. And so I was trying to get some kind of sound out of it. And then I handed it back to her. She says, "No, no." She said, "No, you just keep that. You keep that."

Jo Reed: But how did you learn how to actually play the flute?

Kevin Locke: My mom did have these old recordings, it was from like the '30s. It was from the Library of Congress. And those selections on that recording, that Library of Congress recording, are like the main, best recordings of traditional flute music. And so I listened to those, those two songs, and those are my first two songs, you see? And then from there, I just found a lot of people around, older people, who knew those songs. So those were the songs that I collected, and became my repertoire.

Jo Reed: And you would just ask them to hum, and you would play along with the flute until you got it?

Kevin Locke: No, no, they'd sing them. There were no flute players when I started. But I knew how it was supposed to go. Because I'd been around-- his name was Richard Full Bull, that flute player-- and there were others just at that time, who died all about the same time. So I heard them. I knew how to take the vocal compositions, and to translate them, or instrumentalize them on the flute. Any of the singers at that time during the '70s, older generation singers, they all knew those songs. They're called love songs, but they're not all about love. They explore all the themes that you hear like on popular music, where there's opera, or country western, whatever. They're… people are broken-hearted. Unrequited love. So many of them are about people who are romantically challenged. These kinds of songs. And so everybody had a stock of those songs, but they're very unique compositionally. They're much like haiku, because they follow a formula. It's a very strict formula compositional rule. So usually one phrase, very cryptic, they'll repeat it three times in the beginning of the song, and then the melody will change quite drastically, and then the second part of the song, it'll like expose, or shine a light and give meaning to the first cryptic part of the song. And the song ends with the repetition of that first cryptic opening. So they're very formulaic. So much so that you can easily identify those songs when you hear them. It's like a poetic form that-- a literary form which is so unique, and really widespread throughout many regions in North America. That tradition so bespeaks the social life of the pre-reservation days-- the rules of interaction-- because at that time, years ago, I think young people, they could interact freely, but then when they reached probably puberty, then they separate them according to genders, because they have to go through their gender-specific training to acquire the subsistent skills. Because there's no joke living out in that area, like it goes down 30, 40 below in the winter. You gotta be sharp. You have to know what you're doing. So they have to learn those skills before they're eligible for marriage. But then in the meantime, those social skills are not developed. So then this genre of music became the medium through which they express themselves, you see? That's how that came about. So see, even in the early reservation times, there was so many songs in that genre, that they just... they just continued on.

Jo Reed: Is that pretty distinctive to the Northern Plains culture?

Kevin Locke: No. The rules of composition are defused throughout a wide region. So all the Great Lakes people, they have the same compositional rules for that genre. Even down to Oklahoma. And the flutes that they make are in the-- it's kind of like a step off of a diatonic scale. It's a step off of a diatonic scale. So you can get Kiowa flutes, Comanche flutes from Ponca, from Oklahoma, and they'd be on the same scale as like Menominee, Ojibwa, or Meskwaki or Ho-Chunk, from the Great Lakes. So they could all play the songs on flutes crafted in these very different widespread areas.

Jo Reed: Dance is something that in Native American culture, it has quite a different meaning than in European culture.

Kevin Locke: I think so.

Jo Reed: Can you explain?

Kevin Locke: I kind of-- I like, maybe I just exaggerate to make the point, but I'll just say the dominant culture-- you know, I always think that in the dominant culture, music and dance are what I would maybe say are superfluous activities. They're extraneous. They're not intrinsic activities. Whereas, in most indigenous cultures throughout the world, music and dance are obligatory activities. They're obligatory. You have to participate. And so that's the difference right there. And I always think that in many cases, for indigenous cultures that I've observed, the use of music and dance is quite different. Because you know, you drive around, you watch people, they're plugged into their little earphones and they're in their cars, and they're just zoned out. They have stressful, routine lives! And they want to, they want to just escape all that, you see? So then they tune into music, or whatever, to kind of give them a release, and they just escape that reality that they're in, you see? Whereas, I find that indigenous people, especially here in North America, they use music for the opposite purpose, you see? We use it to connect with that which is real, and good. That which is holy. That which enables all these barriers to collapse and to dissipate the barrier between ourselves and our ancestors. That disappears, you know, through music! There's a continuity there. The barrier between ourselves and the future. That all disappears. The disconnect between ourselves and nature, we reverse that, and we connect through music and through dance. So that's how we do it, yeah. <laughs>

Jo Reed: I'd like to talk about the hoop dance.

Kevin Locke: Yeah.

Jo Reed: And how you learned that is, I think, it's a very compelling story, if you don't mind sharing it.

Kevin Locke: Yeah, I can tell a little bit about it! Yesterday, you know, we flew into Newark, and then I was thinking about that, we flew right over the Statue of Liberty there. And that's where I was in 1980. My buddy, who was really like, I think, the best hoop dancer on the planet at that time. You know, we were doing some shows at Liberty Park. And so that's where we were. We call each other brother-- and his name was Arlo Goodbear from Shell Creek, North Dakota. It's on the Fort Berthold Reservation. So he said, "Brother," he says, "This hoop dance that I have here," he says, "I'm going to give this dance to you." He was a joker, he liked to tease. So I thought he was just setting me up for a joke now. But I looked at him, and he said, "I'm serious. No! I'm going to give you four lessons," he said. "I'm going to give you one lesson now, and I'll give you the rest later." He said, "I'm gonna do my part, and you do your part." And he says, "When you do your part," he says, "Through this dance, you're gonna meet many people, see many places, have many wonderful experiences, and receive just abundant blessings." He said, "You'll get all that, if you do your part," he said, "But I'll do my part." He just had his hoops there, and he broke them out, and he just showed me a few designs. Maybe it took ten minutes at the most. And he had me repeat them. The next day, we took off back out West. Not too many days after that, then, I got a call from his family. They told me that he had died. And that they wanted me to be one of the pall bearers. So then I did that. And interestingly, his brother gave me his hoops that he used. Just gave them to me, you know? I didn't ask why. He just came over and handed them to me when I was at the funeral.

Jo Reed: But the hoop dance is so complicated. How did you learn it?

Kevin Locke: Shortly after that, I had a series of dreams. Basically what I saw in these dreams was that I'd see him dancing. I'll give an example. I could see him dancing. It was dark. But then I'd hear the music, and I could see him dancing. And there was a little bit of light there, I could see him. And as he would dance, he began to create designs. And when he'd make the designs, the light would come out. That light would expand, and I could see the people gathered all around there, but they were all just so downcast, so downtrodden, so sad, and so heartbroken, you could see the way they carried themselves. It was like that. But then when he began to create designs with the hoop-- the hoop, of course, is, it's again, it's a universal archetype. Represents all good things. You know, peace and unity, harmony, balance, beauty, continuity, eternity. Everything good is conveyed by the symbology of the hoop. So when he began to dance with that, he began to create designs, like designs of springtime. Like flowers, trees, birds, butterflies, animals, stars, everything, see? Then when he'd make a design, like flowers, then I could see in the people, the capacity that we all have to blossom, you see? To bring forth color, to bring beauty, to bring blessing. Now there was no language that I was hearing, it was images. It was visualizations that I could see in my dreams. And so then, after a series of dreams that I had, they ended like that. Then I recalled what he said-- that he would continue the lessons, he'd give me four lessons. And then I realized he did his part. <laughs> He did his part. Now it was up to me. But then, so I didn't know what to do. And then interestingly, he had obligated himself to go on this eight-week USI-- it's a State Department tour-- U.S. Information Service tour to Africa. So then, after he died-- well, they asked his mother if she could recommend somebody to go in her son's place. So then she said, "Well, take my other son." She meant me. It's just the way they are, the elders are. And we're that way, too. She says, "Take my other son, he can do it." And so then they asked me. But I knew I couldn't take his place, because I didn't know what to do. Oh, I said, "Well, okay, I'll try. I'll try to take his place." That was all I could say. Couldn't say I could do it. I didn't want to say I couldn't do it. So anyway, I went on that tour, and then the first place we went was to Dakar. And so the rest of the group, they're all going around, they're trying to-- I guess, they gave them a little decompression time for jetlag-- but I-- practiced, practiced, practiced. You know what? Because the dreams that he gave me, they were not instructional. They weren't recipes how to do the dance. They just told me the meaning behind it, see? And that's all I got out of that.

Jo Reed: And patterns.

Kevin Locke: The patterns. Yeah, I could see those. The storyline, I got that. So that's what I was trying to replicate. But then, see, we did-- we were doing like two, three presentations per day for two months, really. I'm sure at the beginning, I was just awful, you see? But then after a few days, I started to get a little pattern going. And I started to add on, add on. And so after about a few months, I started to have a nice little routine going. So I just kept on adding on to that, see? So that was really fortuitous that I started over there. And I'm sure it was all part of some big plan going on that I wasn't aware of. But everything he did predict, it came to pass. Since that time, 35 years ago now, really, I've been able to tour and perform in, I think it's over 80 countries.

Jo Reed: When did you begin to bring the Lakota language, stories, songs, dance, into the classroom?

Kevin Locke: I was enlisted in Teacher Corp, which was one of the Great Society programs. It was to develop teachers from local community to work on the reservation areas. So then, that was through the University of North Dakota. And I found that I was very poor in classroom management, and I'm still that way. I'm a very poor disciplinarian. Very lax in that regard. So then, what I found, the way I would engage the kids, is I'd get them involved in different music and dance. And I'd just use the arts to do that. I think around 1979, the arts council there-- now this would have been the South Dakota Arts Council-- they didn't have any tribal people on their artist roster to offer programs for the schools. So then they approached me and asked me if I could do some presentations. And I said, "Yeah!" So I officially became part of the roster of the South Dakota Arts Council. And then I used to do a lot of Artists in the Schools presentations. And so eventually, it just got to the point where even though I was initially a full-time teacher, and then I became a school administrator. Since about '84, I've just been freelancing. I say, like self-unemployed. But doing a lot of school programs. And so I've been doing that since then.

Jo Reed: You've developed a curriculum.

Kevin Locke: Yes, yeah, yeah. Yeah, we're trying to revitalize the flute. The traditional flute. Around 1980, there was a gentleman who was making the traditional tune flutes. But he found that they were not commercially viable. So then he started making these flutes on a minor pentatonic scale. It's called the melodic scale. That's not a traditional tuned instrument. It's a very modern creation. But everybody thinks that that flute, that tuning system has some relationship to native North American musical aesthetic. But it doesn't, you see? It doesn't. So meanwhile, the traditional tuning system kind of died out. And there's really only like one guy I know that makes the traditional flutes. Anyway, what we decided to do was to introduce this traditional tuning system. And so we developed a curriculum and the flutes that we make-- we make the flutes with the kids-- and so I've been making hundreds. And maybe it's been thousands now in the schools. And the flutes are very versatile, because you can get the traditional like Lakota, or Meskwaki, or any of-- Kiowa tuning system in there, but you can also play the chromatic scale, full chromatic scale. It's really versatile. You can play the full diatonic scale, and two pentatonic scales.

Jo Reed: You had a screening of a video recently in Washington, D.C.

Kevin Locke: Yeah. Oh, yeah. It's called Rising Voices. It'll have a national release very soon. And it's a documentation on the Lakota revitalization initiative. I think a lot of the listeners, whoever's listening to this, know that there's currently 140 tribal languages spoken in the United States. And within a generation, it's predicted that that will be down to probably a dozen to fifteen, because of the fast attrition now. Where there's a--

Jo Reed: Wait, you're saying it'll be reduced by a dozen, or reduced to a dozen?

Kevin Locke: Reduced down to about twelve. It's very fast, because now like every month, practically, there are languages dying out. We have one language in North Dakota, it's Mandan. You know the language that Lewis and Clark, went in that. There's only one speaker left, one fluent native speaker left. Arikara, there's basically no fluent speakers. There's a lot of people who grew up with it, but they maybe lack the confidence to converse in it. So these languages are just dying out at a very rapid rate now. There's just a few that have potential to be stabilized. And Lakota is one of them. And we have so many speakers of Lakota that we could actually revitalize it. And so this is what this documentary is about. It's a situation that's happening all over the world. But it just happens that the United States is one of the most critical places of language loss on the planet right now.

Jo Reed: Are you finding that the younger generations are interested in these traditions?

Kevin Locke: Yes. I see this for Lakota. It's young people, who are educated, very intellectually gifted, who have the capacity and the willpower to do this. Most of the native speakers would be like in their 60s and 70s, and so a lot of them, you know, even though they're actively speaking the language, they may not have the drive or initiative to really spearhead it. Whereas, the younger people do.

Jo Reed: Yeah.

Kevin Locke: Yeah.

Jo Reed: We're sitting here in the Library of Congress and getting ready for the 2015 National Heritage Awards. And of course, you were a recipient in 1990, I believe.

Kevin Locke: Yes.

Jo Reed: I'd like you to just share your thoughts about the National Heritage Award. And what it means to have an award like that in the United States.

Kevin Locke: Oh, it's fantastic! Because you know, the United States is noted all over as being so much into development and putting the past behind itself. And I think it's such a great thing that this award is receiving more and more attention, and the awardees are receiving more recognition. And so I'm really excited to be a part of it. And again, the whole idea behind it for me is that this focuses on these traditions that connect all people throughout the world. You know, there are so many art forms or forms of expression that are just passing. You know, they'll have popularity maybe now, but they'll soon be forgotten. But these traditional arts, they have continuity. So they connect us all the way back to the past. And I think there's more and more awareness of the imperative, the need to make these connections now throughout the world.

Jo Reed: I think about that when you do your hoop dance, because you have 24 hoops.

Kevin Locke: Yeah, usually, it's 28, yeah.

Jo Reed: Or 28. But then by the end, it's one pattern.

Kevin Locke: Yeah, yes.

Jo Reed: It becomes one.

Kevin Locke: Yeah, yeah. I think it's underlying vision that the Lakota people have. See, in our language when we talk about socio-political groupings or ethnicities, we say, <speaks Lakota>, Hoop of the Nation. It's just the way of describing peoples. And so the vision is that the people, the Lakota people, in the future, will be one of many hoops, you see, that will form one great design, one great hoop of unity in the world. And so that we all have something beautiful to contribute to an emerging global civilization. So each of these diverse peoples in the country, in the world really, has some unique special gift, which is so much contained in these individuals that are the recipients, you see, of the Heritage Award. And so then, it just gives you that hope, that realization that it's possible! That we can offer these gifts and thereby empower one another to achieve that destiny! And from there, just to soar off as a collective human family.

Jo Reed: And there we'll leave it. Kevin Locke, thank you so much.

Kevin Locke: All right, you bet!

That is Lakota flute player, hoop dancer, and 1990 National Heritage Fellow, Kevin Locke.

That was my 2015 conversation with Lakota flute player, hoop dancer, and 1990 National Heritage Fellow Kevin Locke, who passed in September. He will be missed and remembered by many. To get a sense of the way folk and traditional arts accentuate the nobility of the human spirit as Kevin suggests, mark your calendars for November 17 when we’ll premier a film that documents the extraordinary work of the 2022 National Heritage Fellows. Go to arts.gov for more details.You’ve been listening to Arts Works produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. Follow us wherever you get your podcasts and leave us a rating on Apple –it helps people to find us. From the National Endowment for the Arts. I’m Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.

Kevin Locke passed away on September 30, 2022. He was a Lakota flute player, hoop dancer, teacher, and 1990 National Heritage Fellow. In this 2015 podcast, Kevin Locke talks about learning to play the Indigenous flute—which had been on the brink of extinction, his work in the revitalization of the Lakota language, and the difference in meaning dance has in Indigenous culture as compared to European culture. Locke also describes the Hoop Dance and its significance—the Hoop Dance is another traditional practice that almost died out—in which he uses 28 wooden hoops to create a series of designs and patterns. Locke also discusses the universal importance of traditional arts and how the specificity of them creates connections. We’d love to know your thoughts—email us at artworkspod@arts.gov. And follow us on Apple Podcasts!