NEA National Heritage Tribute Video: Wayne Valliere

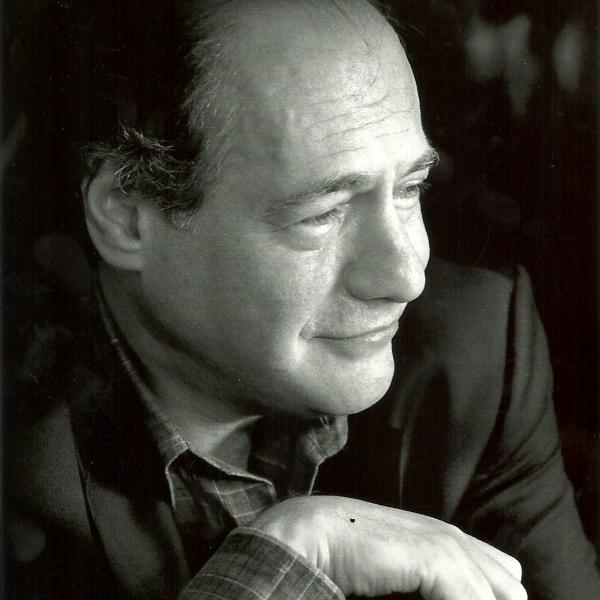

Birchbark canoes are considered an apex of Anishinaabe culture—aesthetically beautiful objects that for centuries represented one of the most sophisticated inland watercrafts in the world. Mino-Giizhig (Wayne Valliere) is one of only a handful of Native birchbark canoe builders today in the United States, and he has dedicated his life to carrying his culture forward through traditional arts.

Born with a white streak in his hair, it was said Valliere would be an elder before his time. According to Valliere’s grandmother, it signified that a “spirit of an old Indian” went into Valliere.

From a young age, Valliere took a great interest in Anishinaabe culture. In high school, he learned to paint scenes of traditional Ojibwe life. Over time, he became increasingly interested in producing the traditional arts that he was depicting in his paintings. He spoke with elders, like Joe Chosa, Marvin DeFoe, and Ojaanimigiizhig, to learn to construct the crafts he painted. Later, he began studying ethnographies and working with historical artifacts to reverse-engineer historical technologies and crafts.

Valliere has a vast artistic repertoire: beadwork, quillwork, regalia, drums, basketry, pipes, lodges, weaponry, hunting tools, and more. He is a respected singer and storyteller. But of all these talents, he is best known as a birchbark canoe builder, a craft he learned alongside his brother Leon.

Because of the craft’s complexity, it takes years to learn to independently build a canoe. One must have a deep understanding of the forest to locate, harvest, and process natural materials for the canoe: thick, pliable birchbark for the hull; straight-grained cedar for ribs and sheathing; spruce roots for stitching and lashings; and pine pitch, which is mixed with oak ash and deer tallow to tar the stitching.

In older times, birchbark canoes were used for transportation, fishing, harvesting wild rice, and hunting. Canoes still are used in these ways. They are a way of life, and they represent a way of perceiving the world for Anishinaabe people. In the Ojibwe language, for example, the words for the bow and stern of a canoe—niigaan jiimaan and ishkweyaan jiimaan—also refer to the notions of the future and the past, conceiving of one’s passage through life as a journey by canoe.

Valliere, who works as an Ojibwe language and culture teacher at the Lac du Flambeau Public School, has been actively working with apprentices and other Native communities to help keep this important art alive. He was recognized for this work in 2015 with the Jennifer Easton Community Spirit Award from the First Peoples Fund, and a 2017 Mentor Artist Fellowship from Native Arts & Cultures Foundation. From the ceremonial harvest of birchbark and sacred cedar to the creative and innovative modifications to the process of their construction, these canoes carry culture and traditional knowledge. They carry identity and worldview. They carry the future of the Anishinaabe people.

By Tim Frandy, Western Kentucky University