Art Talk with Michael Vasquez

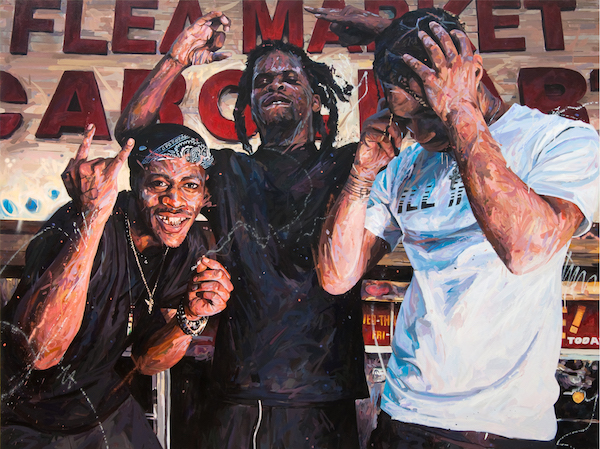

The great painter Edgar Degas is credited with saying, "Art is not what you see, but what you make others see." It is hard not to see the truth of that in the vibrant, oversized portraits of street life by Miami, Florida-based visual artist Michael Vasquez. Where some of us might see street thug, gangster, fear, Vasquez sees acceptance and connection. He sees boys trying to figure out how to be men. He sees people trying to craft home out of what is broken, what is overlooked, what is looked away from. The paintings often start as photographs, which are then transformed first through collage and then through paint into layered investigations of the postures, gestures, and settings that comprise what Vasquez describes as his subject's energy. When we spoke with Vasquez via telephone for this interview, he noted that even as he explores the lives of others through paint and canvas, he in turn learns about himself and what drives him from the work. "Art at least for me was a tool of self-discovery. I realized each thing [I painted] was about growing up without a father figure," he said. "I made the art, I looked at the art, and then I had these revelations, 'Oh wow, maybe that's why I'm making this stuff.'"

NEA: What’s your origin story as an artist

MICHAEL VASQUEZ: The second grade is my earliest memory of me realizing, "Oh wow, I like this art stuff." I was in this combination class of second- and third-graders, and there was this kid in the third grade that could draw really well. The other students would crowd around him to see what he was drawing, and when he was done they would ask him if they could have it. I recognized the attention that he was getting from his peers from just creating something. I was attracted to looking like I was cool, so I decided that I was going to learn how to draw, whatever that meant. [I started] checking out books from the library like how to draw horses, how to draw people…. Art became not only a hobby, but this passion, and it's something that would grow with me through the years.

My interest in art evolved, ultimately, to being interested in graphic design, specifically in the realm of apparel. I pursued a degree in graphic design upon graduating high school but in the midst of that I figured out that I really didn't want to do graphic design. I came to a realization that there was this other option of being an artist, like a “real” artist, [laughs] is what I called it. What I mean by that is someone that's making the work that they want to make and being recognized [for] and supported by it. Where I grew up in St. Petersburg, Florida, we never really had an art scene so the idea of being an artist was something foreign to me. It turned into something more commercial, and that's what led me to this idea of becoming a graphic designer because I could go to school, I could become superior in this thing, and then I could hopefully get a job with this degree doing this stuff.

While I was in college at the New World School of the Arts, I realized that being a fine artist was an option. There were students there, actual peers of mine that were a few years ahead, and they were already making the work that they wanted to make, and getting recognized and supported for it. I thought that was awesome, you know, this idea of really I can do what I want to do. I can make the things that I want to make; someone else isn't dictating what I'm doing with my time from day to day. In an entrepreneurial sense, I liked that idea of freedom, of being able to control exactly what I wanted to do.

NEA: You work lot in portraiture; what does it mean to you to make someone's portrait?

VASQUEZ: The straightforward definition is that a portrait is a visual presentation of identity. [There are] all kinds of things that can inform this idea of identity. There are aspects of likeness--does this look like this person or not? Other visual cues that are present in the portrait [include] where is the setting of this portrait, patterns, and sort of any sort of specificity, like clothing and things like that. All these things together inform… this identity that's being presented. In my painting I hope to touch on those things, but more importantly, I hope to be able to capture this attitude or energy of the subject and the environment the subject is in.

NEA: What really struck me about your work was that the paintings were making beautiful these places and people that we don't necessarily see the beauty in.

VASQUEZ: My work is loosely inspired off my personal history ... I mean that certainly is the starting point. I grew up as an only child to a single-parent mother, so I didn't really have a father figure in my life…. I met the kids that were in the hood, and some of them were either in or associated with this neighborhood street gang. I didn't realize all the stuff at the time but… not having a male figure in my life to guide me, and also not really having any brothers or sisters, [I was attracted to] this neighborhood street gang [because it] embodied many stereotypical traits of masculinity, this kind of shallow, bravado, toughness that to a young teen that's trying to become a man would be attractive.... The work that I make was basically demonstrating this story, this concept of this child and his relationship with his family, home, and then this relationship with kids in the neighborhood. I have been stuck in [making work about] this neighborhood. I don't want to say stuck, in a bad way, because there's many things that I want to explore now that are a part of this subject matter. Visually there's things to explore and psychologically there's things to explore. There's social aspects that I often explore and certainly identity. Talking about portraiture, say you're talking about a portrait of a gangster, for me in many ways this gangster is the perfect subject for a portrait that can be visually rich in the sense that the gangster has visual cues that he has to uphold and that inform his identity, his affiliation. These visual cues that this person exudes can make for a very rich portrait.

NEA: Can you talk a little about how you work? I wasn't sure if you worked from photographs or people coming to the studio?

VASQUEZ: Most of the portraits started as photographs that I [took] during a photo shoot. [It might be] me going to them, which is usually what I prefer, because I can capture them in their environment, and the things that are in the background can inform the viewer more about this person's identity. But sometimes I have them come to the studio and do it here because I can control things a little bit better here in terms of lighting, and the whole set up. Often in that case, the background would then get Photoshopped in…. I have some portraits where I have these aerial views of a neighborhood, like one would see on Google Maps, that sort of thing, behind the sitter…. Sometimes collages happen with the photographs. I'll print out many photographs, and then I'll cut them up and collage them, different guys with different photos, different backgrounds, different objects. I take the pieces from these photographs and then put them together to create this collage and then the collage is recreated in the computer, and then I work [on a painting] from that sometimes.

NEA: It's interesting to hear you talk about collage, and Photoshop, and the different ways you manipulate the starting image into a narrative. Do you think there's a certain narrative you keep trying to tease out or that you're drawn to again and again?

VASQUEZ: Sometimes I feel like I’m telling the same story over and over, but that is not necessarily a bad thing because there's different things, different details that can be discovered by telling the story over and over again, different ideas to take note of. To sum that story up, it's really acceptance. It's about feeling a sense of belonging, being accepted, by your peers.

NEA: Your work is about looking at others. As you're looking out at others, what do you find out about yourself, or what do you think that you're revealing about yourself?

VASQUEZ: I think about that sometimes--why am I drawn to this sort of subject matter? I've been making this kind of work now for 10 years. That's a long time to be doing something... I guess I realized that it helps me realize the value in relationships between people, bonds that people create and that connect people.

NEA: Your Neighborhood Reclamation series is a series of urban landscapes. How does that relate to your portrait work, or is it a completely different direction?

VASQUEZ: On the surface it definitely seems like a different direction, but for me it's all the same stuff.… The landscape sets the stage for the other work; it's where all that other work happens. This landscape can tell us, or inform us more about why people gravitate toward that sort of street lifestyle. [I’m] taking these photographs of these homes and then trying to invigorate them, give them this hope or life, even make improvements to these structures in some cases, through this process of collage, and then taking the collages and translating them into paintings, again with this idea of like energizing the landscape through paint.

NEA: What is the role of the viewer or the audience in your work? Do you think about them at all?

VASQUEZ: I like painting at a large scale for all kinds of reasons, but one of the main reasons is to literally position the viewer under these people, looking up to these larger-than-life portraits of people that, I don't want to generalize and say most people would look down on, but that maybe people would pass in the street and not look twice at them, or [would] feel too intimidated to look twice at them. This gives the viewer an opportunity to connect with these people, because hopefully there's not only this visual presentation of this person, but there's also this energy and sort of mood that's created with the painting that the viewer can actually connect with this person's energy that's translated through the paint.