Making Design a Necessity for Good Government

In April 1973, NEA Chair Nancy Hanks delivered the closing speech of the First Federal Design Assembly. The objective of the three-day conference was to stress the importance of improving design in the federal government. The event attracted more than 450 federal officials to collaborate with 500 designers in attendance on design challenges facing the government. Hanks summed up the assembly as a new era of federal design because “today, instead of a few isolated people, there are ranks of administrators who equate good design with good government.”

The Federal Design Assembly was one of the first programs coordinated as part of the new Federal Design Improvement Program (FDIP), which sought to enhance graphic design, design hiring practices, and architecture within the federal government. The co-chairmen for the First Federal Design Assembly, Ivan Chermayeff and Richard Saul Wurman, noted in a press release that the U.S. government is the “country’s largest planner, builder, landlord, and printer,” underlining the integral role of design in government. In the final report of the event, it was noted, “…as human needs have become more complicated, and human beings more numerous, the design necessity has become more intensive.”

In an effort to summarize the ideas at the assembly, the NEA and MIT Press published Design Necessity, a casebook to articulate the impact of positive design performance on governance. The primary topics of discussion were visual communications, interiors and industrial design, architecture, and the landscape environment. The casebook served as a catalyst for future assemblies and outlined a cohesive identity for federal design.

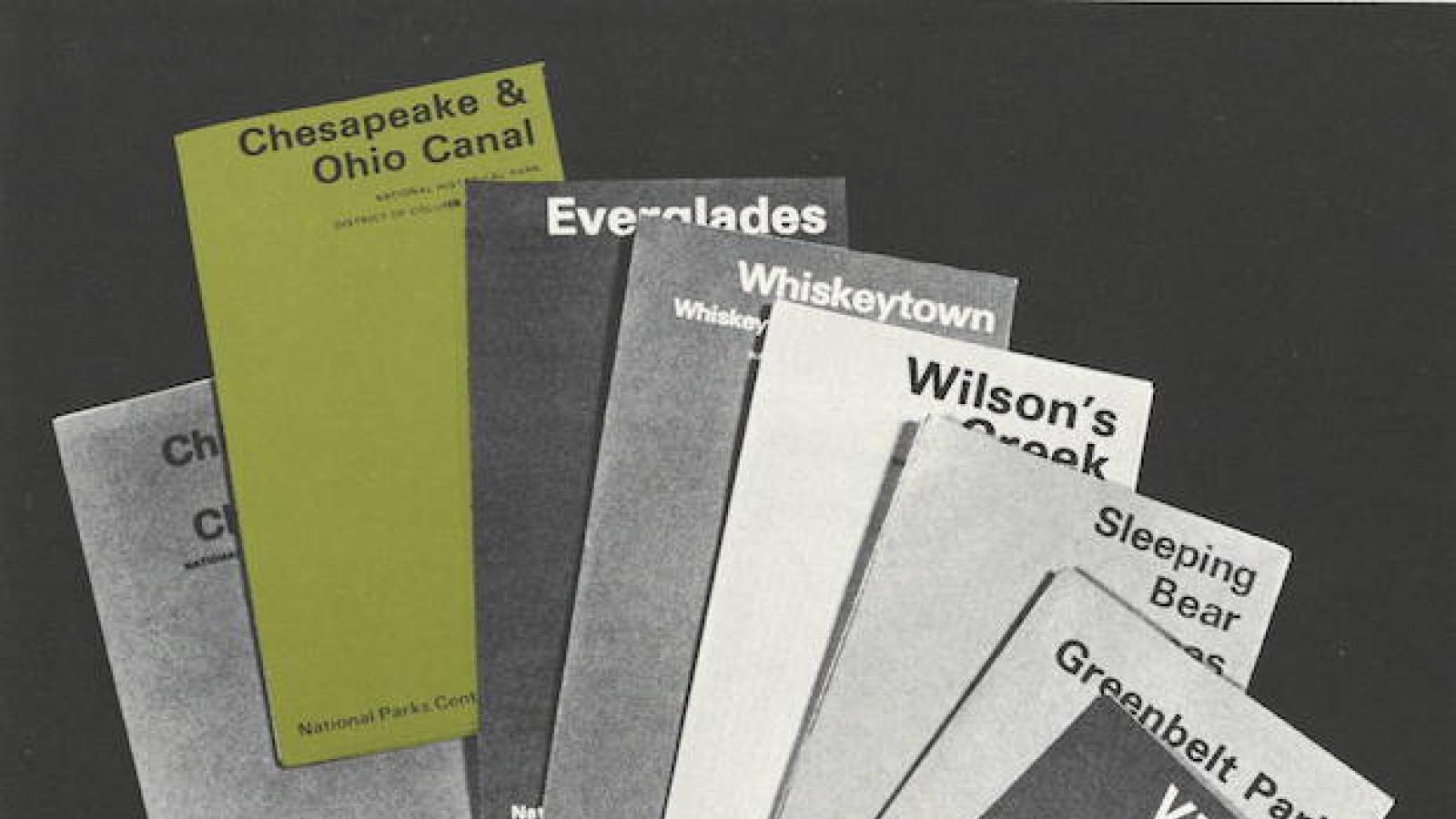

The ideas and projects presented in Design Necessity focused on good design as a way to save time, enhance communication, and decrease costs. One example of improved visual communications was the National Park Service’s (NPS) “Minifolders.” The Park Service distributed thousands of free brochures every year to park visitors. The folders, however, were expensive to produce and did not meet the regulations of the Joint Committee on Printing, which deemed them wasteful. The redesigned Minifolders were brochures that provided the same information as NPS’s previous publications in a condensed form. The project successfully lowered the cost per brochure from 4.5 cents to 2.5 cents. Vincent Gleason, chief of the Division of Publications, estimated that the combined time and money saved by the simple design modification was 20 percent across the board.

In addition to visual communication issues, public transport challenges were also discussed. Boeing and the Urban Mass Transportation Administration collaborated to build a new transit system in Morgantown, West Virginia—home to West Virginia University. Prior to the project, the 11,000-person student body depended on 17 buses to move across three separate campuses. The idea was to establish a Personal Rapid Transit System (PRT). The system consisted of more than 70 “pods” holding up to 21 passengers. Along with their small size, a design modification was that it did not have a set schedule. Passengers simply pushed a button to summon a pod. The tracks were also heated so that school could stay in session during the snowy winter months, which had not been possible with the previous use of buses to tackle the icy Appalachian hills. The project presented a new approach in administering public transit that focused on passenger needs and efficiency. The project is still in existence today, carrying up to 4,000 passengers an hour and serving an expanding student body of 28,000 students.

The Design Necessity projects covered a large range of applications, but shared an embrace of good design. They were presented as examples to convince federal administrators of the necessity of design in governance. Shared with the public, the ideas and projects became part of an outreach initiative to spread the word. Nancy Hanks sent a copy of the publication to all state arts agencies and contacted each state’s governor to galvanize support for good design at the state level. The momentum and positive media response to the assembly led to future design assemblies and strengthened the relationship between designers and government officials.

Subsequently, countless projects grew out of the design assemblies hosted across the country both at the federal and state levels. As a result, more literature on the intersection of government and design was published, generating a national conversation among administrators and designers. The NEA played an integral role in promoting the value of good design—as it still does today—helping administrators to appreciate the role of good design in good governance with initiatives such as the Mayors’ Institute on City Design.