Spotlight on Canto Mundo

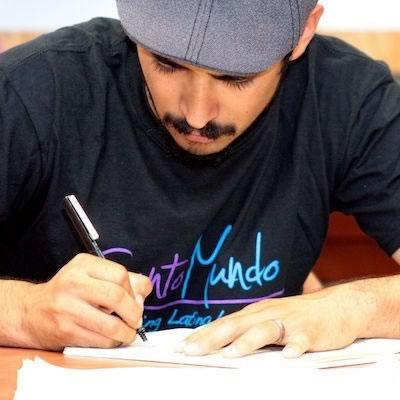

Poet Marcelo Hernandez Castillo at a CantoMundo workhop. Photo by Alberto Gonzales

“Where is the Latino Cave Canem?” This is the question that brought Deborah Paredez, Celeste Mendoza, Norma E. Cantu, Pablo Martinez, and Carmen Tafolla together in 2009. Shortly after, CantoMundo was born. The first organization of its kind to specifically cater to Latino poets, CantoMundo’s mission is to provide a supportive environment in which self-identifying Latino poets can come together to not only learn from one another, but to also cultivate a network dedicated to uplifting their communities. With support from the NEA, CantoMundo presents a yearly retreat that includes keynotes from accomplished poets of color and writing workshops for the fellows. Award-winning poets such as Denice Frohman and Eduardo C. Corral are just two of many CantoMundo fellows who’ve not only made great strides in poetry, but great strides in their communities.

To celebrate National Poetry Month, Deborah Paredez spoke with us about how CantoMundo came to be, the benefits of such an organization, and how CantoMundo poets are working to shape their communities every day.

NEA: What exactly is CantoMundo?

DEBORAH PAREDEZ: CantoMundo is a national organization that supports Latino poets and Latino poetry. We were founded in 2009 by myself and my four other co-founders: my current co-director, Celeste Mendoza, Norma E. Cantu, Pablo Martinez, and Carmen Tafolla. We were a multi-generational group of poets, all of us Tejano Mexican-American, who had been very much inspired by the work that had been done by the organizers of Cave Canem and Kundiman, which of course have both been supported by the NEA. They’re respectively organizations that represent African-American poets and Asian-American poets. They were both founded before we were… so we asked ourselves, “Well, where's the Latino Cave Canem?” We finally realized, “Well, we have to make it.”

NEA: What is the significance of the name CantoMundo?

PAREDEZ: Pablo Martinez came up with the name because we were interested in creating this kind of space in this world. We wanted a name that evoked that kind of world-making or that placemaking sensibility, as well as a world that really reflected a history of Latino poetry and song-making. So Pablo picked the word canto which means song and mundo which means world so this idea of… referring to both the long tradition among Latino and Latin-American poets of creating a “song world,” and also trying to create this space for Latino poets to have their voice and share their voices with one another.

NEA: One component of CantoMundo is bringing Latino poets together for a retreat. Can you speak a little more about this?

PAREDEZ: Again inspired by the model of Cave Canem and Kundiman, the retreat consists of a four-day writing workshop…. We tend to have between 24 and 30 poets attend each year. We find that to be a good number so there's a robust diversity, but also not so many that people can get lost in the shuffle.

Once the poets get to be CantoMundo fellows they can attend up to three total workshops over a five or six year period. This helps us facilitate more long-ranging relationships amongst the poets as well as allowing them to provide mentorship to the newer fellows who come in. We hold an opening circle the night they arrive and then they attend both writing workshop and panels. The workshops are taught by very well established leading Latino poets in the country. Last year we had Juan Felipe Herrera, the current [U.S.] poet laureate. The workshops are faculty-led generative writing workshops where poets come together, create work, and then share it.

Something we also do that is really important to us is we invite a poet from another community, who is not Latino, but who is of a community who's often underserved or historically marginalized, to give a keynote speech after the opening circle. Not only are they invited to read their poetry, but also to talk about how their work with other communities has informed their own poetics. Our first keynote speaker was Toi Derricotte, who is one of the founders of Cave Canem. [We’ve also had] Natasha Tretheway and Nathalie Handal, who’s talked about her experience with Arab-American poets, as well as members from Kundiman.

NEA: How do you think bringing in poets that represent another group speaks to the mission of the organization?

PAREDEZ: I think it literally embodies the very kind of coalitional cross-cultural influences of our own formation. It also really speaks to the fact that many of our poets themselves are members of multiple communities. We have Afro-Latino poets, Jewish-Latino poets, and Filipino-Latino poets, to name a few. There is such a range of communities that it also allows us never to forget the ways we might be positioned across communities and definitely keeps those lines of communication open. Given the limited resources for artists and for poets, it could be easy to fall prey to the zero sum game like, “Oh no if that community gets something, then somehow there's going to be less of the pie for us,” and we really want to refuse that kind of thinking.

NEA: What do you look for in candidates when choosing program fellows?

PAREDEZ: On a basic logistical level, what we require of the applicants is to write a cover letter in which they talk about their experience, their commitment to communities or what they think of as their own commitment to Latino communities, and then [we also] have them speak a bit about themselves as writers. We do have them include samples of their work and they can write a CV of the places they've performed or that they've been published. While it is important to see how or if they’ve been published that matters less to us overall than thinking about their work and how it relates to Latino communities. For example, we’ve had poets with a long history of working in nonprofits serving Latino immigrant communities. We have others who are absolutely terrified to be with other Latinos because they've been in settings where they've been the only one [Latino] and they’re desperate and also terrified to finally be in a room with other Latinos. We’re eager to serve that wide range of experiences. We want to be able to offer the opportunity to someone who actually might not have ever been afforded that opportunity. We often look at things like diversity of life experience. Some of our poets are in their 20s and have just graduated from college. Some have raised their kids and have a career and are coming to poetry for the first time in their 50s. We have some who are published in the New Yorker and we have some who would never publish in the New Yorker by choice. So we do like to look for that range both aesthetically and in terms of experience and generation. It’s also important to us to, as I mentioned before, to make sure we're open to the wide range of diversity within Latino communities in terms of cultural and national origin.

NEA: What impact do you think CantoMundo has made in the community it serves?

PAREDEZ: It’s been tremendous to see as [our community] has grown how the poets who have had more exposure and access to more established venues in the poetry world have mentored and provided opportunity for the poets coming up through CantoMundo. For example, we have a poet who has been writing with the Kenyon Review, which is very important within the world of poetry. She then provided opportunities for other CantoMundo poets to be published. Once they were published there, it provided opportunities to be published in other places, so the development of a broader network or mentoring which provides professional opportunities has certainly happened. CantoMundo fellows have gone on to receive a wide range of prizes and often acknowledge that their time as CantoMundo fellows has been important.

NEA: What’s next for CantoMundo?

PAREDEZ: We just recently moved to New York City. We're actually based in Columbia University and have some funding through them. Because we’re uptown, I am very interested in having us reach out and do more work with the Latino communities that are uptown in Harlem, East Harlem, the Bronx, and Washington Heights and using our shared interest to think through how we might serve and partner with existing organizations who are already doing that work. Most immediately, we’re actually about to launch a program… as a part of the Poetry Coalition’s programming on migration. We partnered with a couple of different organizations [including] an organization called Letras Latinas, another Latino literary organization based at Notre Dame University. We partnered with them to do a series of blog posts in which Latino poets got together with other Latino poets and showcased their work. We also partnered with another organization that was founded by a CantoMundo poet called Undocupoets. They’re an organization that tries to serve undocumented writers and provide opportunities for them…. We’re going to be doing some work with [military] veteran writers because Latinos are a large percentage of the veteran population. We’re working with an organization called Combat Paper Project. They do fascinating work with papermaking out of veteran uniforms. The veterans come and transform their uniforms into paper and then they write their experiences on them. So our poets are going to pair up with them and do an exchange of papermaking and poetry-making workshop together over a several month period where they are exchanging work.