Grant Spotlight: Celebrating Women's Suffrage at Brandywine River Museum of Art

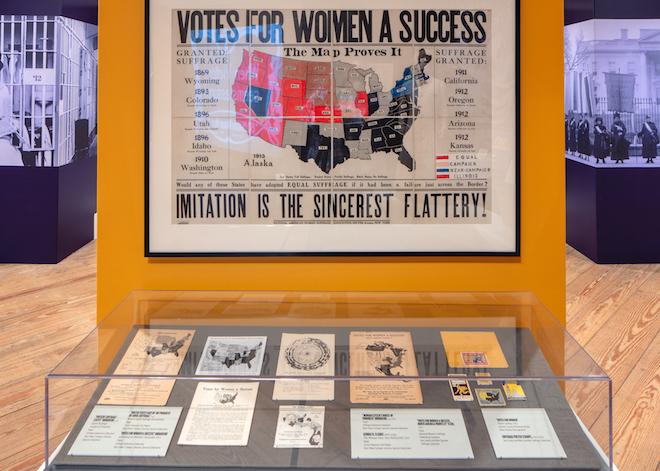

The next time you visit our nation’s capital, if you walk down Pennsylvania Avenue, past the White House, you are sure to see someone standing outside with a sign picketing for a cause that is important to them. If you ask Amanda C Burdan—a curator at the Brandywine River Museum of Art—where the tradition comes from, she’ll readily reply, “I like to think that it all started with the suffragist.” The women’s suffrage movement in the United States spanned several generations, and was unprecedented in its use of visual communication strategies to secure the vote. One hundred years after the passage of the 19th Amendment, with the help of Burdan and grant support from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Brandywine River Museum of Art is honoring the contributions of the suffragists in Votes for Women: A Visual History. While the museum is currently closed to the public because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the exhibition is still accessible through weekly virtual tours on the museum’s Facebook page. The tours highlight some of the costumes, banners, photographs, publications, illustrations, and other objects tied to the visual history of the suffragettes and their pursuit for voting rights. The exhibition also recognizes the contributions of women of color and those who have long been overlooked in the history of suffrage, most notably in a mural, Hidden Figures of the Suffrage Movement, which includes 14 portraits of voting rights activists whose contributions have historically been minimized. We spoke with Burdan about the challenges and discoveries made in developing the exhibition, and what she hopes visitors—whether virtual or in person—will take away from it.

NEA: What story were you trying to tell with this exhibition?

AMANDA C. BURDAN: As a curator, I was looking for a way that the visual arts or visual communication played a role in the suffrage movement. Since visual storytelling is something that we discuss and teach all the time at our museum, understanding how visuals played into the story, the narrative, the arguments, and the campaign for suffrage was my goal for this exhibition. I wanted to find out what suffrage looked like in its time and see if we could bring enough visuals together to get a sense of what it was like in 1913 or 1915 or 1920.

NEA: As I was researching and reading more about the suffrage movement, I learned that it really was a revolution for women. Were any of the visual media approaches used in the movement revolutionary for the time?

BURDAN: Absolutely. There were a couple of things that come to mind, some things that were done before, but not by women. There's one thing in particular that was very visual [and] absolutely revolutionary in the realm of peaceful protests, and that would be the Silent Sentinel campaign. Those are the women who stood in protest in front of the White House between January 1917 and June 1919, taking their message directly to the president with banners that said things like, "How long must women wait for liberty?" It particularly appealed to me, because it was a silent campaign. All of their actions were visual. They stood there to be in sight of the president or all of his advisors, his visitors, and they used banners and signs to communicate rather than making speeches or singing songs. They stood rather motionless. So, it wasn't a performance or a soapbox speech or anything like that. That was truly revolutionary in how protest is performed.

NEA: What were some of the museum programs that are part of the exhibition and how do they help to further your goals for the show?

BURDAN: Well, the kind of programs we often do at our art museum are gallery talks, where I walk through the exhibition and talk to people about the objects. I'm really motivated by storytelling. Seeing the objects connects with the story for me, and for a lot of people. For International Women's Day we had a lot of different kinds of programming. We've often had theater performances at the museum. We did a theater production about Lucretia Mott and Frederick Douglass called Under the Bonnet. We also had a pop-up experience called the Museum of Impact, which had what's called the Upstanders' Festival. In a world of a lot of social causes and things happening, the Museum of Impact encourages people to be an “upstander” instead of a bystander when events are happening. As part of the activities, people wrote letters to women who had been inspirational to their lives. They also created pins and buttons to wear with their own personal causes on the button so they could wear their beliefs on their sleeve and encourage teamwork in all sorts of ways. That brought people together in a unified way instead of more divisive political events.

The things we often do in the museum include First Family Sundays and we have a sensory-friendly Saturday for families with children on the autism spectrum, where we have the museum open for limited activities and quiet time. That's one of the things about this exhibition in particular—since it wasn't a straight-forward paintings and sculpture exhibition, we had the opportunity to reach audiences that had different interests, like social justice, women's rights, and historical interests.

NEA: In the course of putting together the exhibition, what were some of the challenges you faced and how did you navigate those?

BURDAN: One of the major challenges to this exhibition was in terms of conservation of the objects, particularly the objects that were coming from the National Woman's Party, which were textiles and works on paper. They needed a lot of tender loving care to travel and to be on display. They needed conservation work to clean and stabilize and stitch any parts of banners or capes that needed reinforcement. A lot of times in the museum world, if there's an object that you want to show, but it's not in the greatest condition, you end up skipping it, because it's a very expensive project to do a lot of conservation. But in this case, it was so important to have these original objects, the banners and the capes and the drawings that tied directly to the period. The challenge was being able to conserve those items and being able to fund it. It was a real goal of our fundraising to foot the bill for the conservation that needed to take place. It was nice that we could explain to our funders, like the National Endowment for the Arts or the Coby Foundation or private individuals, that these objects that we were conserving, like a flag that was [used] in a suffrage parade 112 years ago, were really being preserved for future generations, not our exhibition alone.

It's a little bit easier to put that financial investment into objects that belong to your institution, but these all belonged to somebody else's institution. But we thought it was very, very important to do this work, particularly for the National Woman's Party collection, which is fantastic.

NEA: Were there any interesting things you learned through the development of the exhibit that you didn't know previously?

BURDAN: For me, there were revelations in looking at the visuals, because I can read books till the end of time, but I really understand and digest visual information a little bit better. One thing that really hit home, looking at the materials, was how very young so many of the women involved in the later phases of the suffrage movement were. It had been going on for decades and there were many generations involved, but I think one of the important parts of the success of the suffrage amendment in 1920 was that the older generations had not given up on the fight, while the younger generations were joining in the fight. Alice Paul was in her mid-20s when she was running this Congressional Union. Harry Burn, the man who cast the deciding vote in the Tennessee legislature, was 24 years old. They were crazy young for doing the important things that they were doing. Seeing pictures of them, I was like, "Wow, she's just a baby and look at what she's accomplished." I think that's a fault of histories as they've been taught or haven't been taught [that] we think of it as a stuffy generation of old ladies from upper-class families that were interested in this, but to see how it penetrated to different segments of society was so interesting. And that goes for women of color as well. The visual materials for suffrage in communities of color is kind of rare. So, when I saw it, it was absolutely amazing. You've probably heard the accusation that the suffrage movement was racist or didn't allow women of color to participate. There was certainly segregation in the movement, but that doesn't mean that women of color weren't also fighting for their right to vote. Finding the visual culture that goes along with that was a discovery, because it's proof that all these women from different backgrounds, from all over the country, were participating—that working women were participating, that African-American women were participating, immigrant women. Seeing the visuals like the handbills for a march aimed at African-American women or the scrapbooks kept by suffragists who were campaigning in African-American communities, that was such a surprise to me.

NEA: Was there one overlooked figure from the suffrage movement that stood out to?

BURDAN: Well, if you ask me on any given day I'd probably give a different answer, but since I was just mentioning that scrapbook, I'm thinking about Alice Dunbar Nelson. I went to see her papers, her scrapbooks, her letters, her personal belongings in an archive at the University of Delaware. I feel a really tangible connection to having learned about her. She's a woman who is known for many things. She was a poet and a writer. She was married to a very famous poet herself and she had notoriety. She had status as a celebrity. In 1915, she was living in Wilmington, Delaware, which is not far from where we are here in the Brandywine. Alice Dunbar Nelson worked for the Pennsylvania suffrage campaign in the summer of 1915. In Pennsylvania, they were scheduled to have a referendum on women's suffrage in November of 1915, so that summer was a really hot campaign time. Alice Dunbar Nelson kept not a journal, but a scrapbook. It's important, because a scrapbook is a lot more visual than a journal. She kept articles that were written about her; her own picture accompanied those articles. She kept handbills from rallies that she spoke at. She had saved some material directed at African-American women and African-American citizens, because, of course, under the 15th Amendment, African-American men were legally allowed to vote, even though voter suppression was taking place. So, it was seeing the things that she saved about what she called a “not-entirely uninteresting” campaign from that year. And then she went on to do other things. She worked particularly during World War I on peace efforts and on supplying African-American soldiers. She had so many different social causes that were dear to her. Maybe someone would know her from her poetry or from her peace work later on, but she had a suffrage chapter in her life as well.

The University of Delaware, which owns the papers of Alice Dunbar Nelson, is working on a digitization project. Among the very first things they digitized was that scrapbook. They had these high-resolution images, which meant that I could use those images and re-create her scrapbook so that people could actually flip the pages and sit and read the passages, the articles, look at the pictures, and page through every part of that scrapbook.

NEA: Votes for Women has a companion exhibition, Witness to History, featuring the photos of the 1965 civil rights march in Selma. How do these exhibitions highlight similarities or differences between the suffrage movement and the civil rights movement?

BURDAN: It was important to me and to our institution that no one leave our exhibition thinking that the work for voting rights was done with the 19th Amendment, because there was voter suppression since the 15th Amendment had passed allowing formerly enslaved men to vote. So, the 19th Amendment was sure to have all the same issues. In fact, many of the campaign tactics in, particularly, southern states set about to reinforce and remind the male voters of the state how African-American voters would not be a problem if the 19th Amendment passed, because there were ways of taking care of them. And, so, we saw a parallel with the Witness to History exhibition, because that Selma march and the Civil Rights Act of 1955 was taking the time to close the loop-holes that were left by the 15th and 19th Amendments. You have the right, but in practice, there is intimidation, suppression, poll taxes, literacy tests, and all those sorts of things that have been put in place to edit the voting populace. In Witness to History we focus on just one march. It's a really concentrated view, but that march… so clearly echoes the marches that suffragists had been making to have their voices heard and protest peacefully. The idea of having a march to bring your message directly to your government leaders was something that I saw great parallels to in the suffrage exhibition. And this body of photographs has not been very widely exhibited. This photographer, Stephen Somerstein, took the pictures in 1965 when he was a college student. He was 24 years old, just as young as we were seeing in the suffrage movement. He published a few of those in the school paper and then he put them away until 2010. He didn't go on to become a photographer or a journalist. So, it was a little bit of an uncovering of this point of view of a very important march that led to enacting and enabling the two constitutional amendments to actually fulfill their promise.

NEA: How does Votes for Women balance the progress that has been made when it comes to racial and gender equality, while still acknowledging that we still have a ways to go?

BURDAN: I think one way that we're doing this is with that mural, [Hidden Figures of the Suffrage Movement]. We like to think of that as a conversation starter. There's a conversation that's still to be had in history among citizens, at institutions, libraries, universities about the role that women of color, or in the 1960s, people of color played in securing the rights of others to vote. By pointing out and telling the stories of women who you hadn't heard of, I hope that it fosters an understanding that there might be more of those women out there. When I talk about the research on African-American women that I've been doing, realizing that the material is rare but it's out there, it's really a challenge to the kinds of research that we do. Where do you go to do your research? Do you just go to the local university library? Or are you looking at the records, research, and archives of African-American communities or Native-American communities or immigrant communities? I think there's changes in how we research things that are coming forth that I'm just learning, too. I think the mural opens up a conversation about the history that we know. It makes us and the visitors realize that there's more out there, and hopefully, they'll want to know more, as well.

NEA: What do you hope that visitors take with them when they leave?

BURDAN: I think, regardless of your party, regardless of your gender, regardless of your racial background, one thing that both of these exhibits brings home is how hard other generations, other people who've come before us, have worked to secure that right to vote. If you know the history of exactly how hard, how difficult, how painful it was to secure that right that you probably have taken for granted in your lifetime, I hope that people give more thought to exercising that right when it comes to election times, whether it's primaries or later this year. I hope just understanding a little bit more about the history of why you even have the right to vote is meaningful and impactful. And then, as we talked about, because it was a youth movement, that you can't rely on generations before you to make the decisions or to change things. It takes the cooperation of a younger generation to join in whatever that issue is. There are plenty of social justice issues today that are all the better for the participation of the young generation and so, of course, that should apply to voting as well. I would love for people, especially younger people, to be energized and engaged, and actually, maybe some of them will vote for the first time knowing the history behind the ballot they're casting.