Showing What's Possible with Kaya Press

“What we're trying to do at Kaya is to show what is possible,” said Sunyoung Lee, publisher and editor of Kaya Press, a longtime National Endowment for the Arts grantee. Through Kaya’s innovative offerings of diasporic Asian and Pacific Island (API) literature, which push the envelope in terms of content, form, and genre, Kaya hopes to introduce readers to new ideas of what literature in general can be, not to mention what API literature can be about.

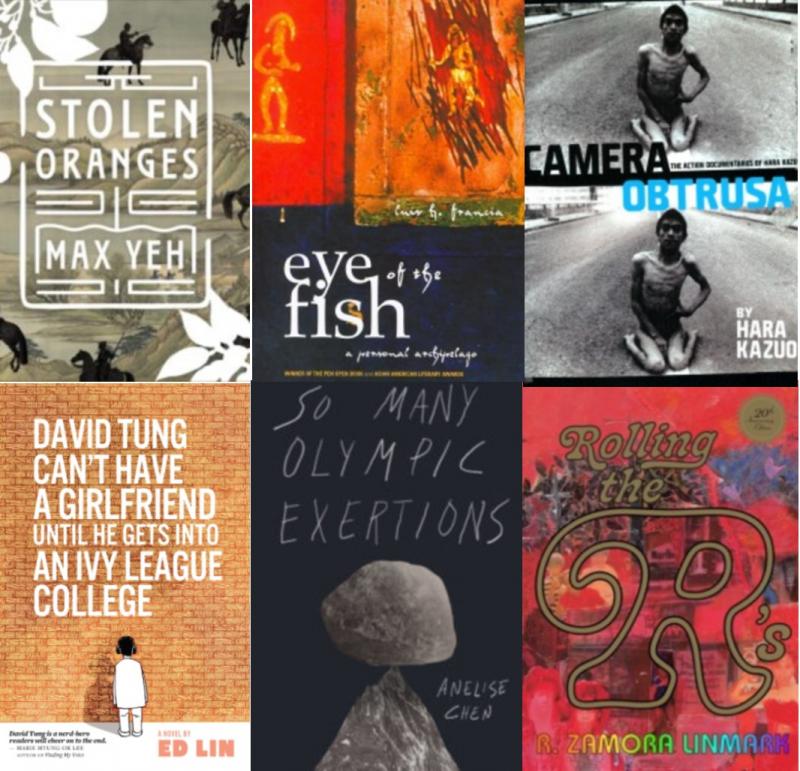

Among Kaya’s diverse list of books include the forthcoming David Tung Can't Have a Girlfriend Until He Gets Into an Ivy League College, the first YA novel by Ed Lin; I Guess All We Have is Freedom, a collection of short stories by Japanese avant-garde artist Genpei Akasegawa; and Stolen Oranges by Max Yeh, which imagines correspondence between the Chinese Emperor Wanli and Miguel Cervantes. Kaya also publishes what Lee describes as “historical rediscoveries,” books that were written or published long ago, that expose forgotten or repressed chapters in our history. This includes Lament in the Night, written in the 1920s by Shōson Nagahara, which describes the literary culture of working-class Japanese Americans in Los Angeles during the 1920s. It was recently translated from the Japanese by Andrew Leong and re-published by Kaya.

We recently spoke with Lee and managing editor Neelanjana Banerjee about what makes their publishing house tick.

NEA: What was the motivation for founding Kaya Press?

SUNYOUNG LEE: The original impulse for starting Kaya was a desire to create an alternative space that was not dependent on mainstream commercial publishing, where you could develop Asian diasporic voices that would have a chance grow into whatever kind of voice they wanted to be, as opposed to being filtered through this mechanism of, "This is the kind of voice we're expecting, this is the kind of story that we're expecting. We want a very specific reiteration of a very specific kind of immigrant success story."

There weren't that many openings for alternative stories and ideas and perspectives. And frankly, there wasn't very much room for Asian diasporic voices at the time when we started, which was in 1994. So that was the original impulse—to create a place where all of these voices could grow and develop and be featured.

NEA: How do you think the press itself has grown and developed over the past 26 years?

LEE: Well, it survived. I think that's always the first and most exciting thing to talk about, because it's not an easy thing.

In terms of growing and developing, one of the things when you continue to persist is you're creating your own history as you continue to grow and thrive. We're not just some idea that sprung up and then faded away. We've been able to see multiple generations of authors that have been published by us, and then inspired other authors that we have then subsequently published.

One example of that is one of the first books we published, Rolling the R's, by R. Zamora Linmark. Rolling the R's is a book that's written primarily in pidgin about these kids growing up in 1970s Hawaii. That book was read by another one of our authors, Amarnath Ravva, who was in college at the time. He said, "If this kind of a book can exist, then I, too, can become a writer. This is something that I can become." And then we published his book, American Canyon, several decades later.

As you're going through it, you don't necessarily notice the effect and the impact you might be having as an organization, but over time it becomes clearer. That's always one of the most gratifying things about being able to persist and survive in this way.

NEA: How else do you think Kaya has impacted not just the API literary scene, but the American literary scene in general?

LEE: The way I always describe what we're trying to do at Kaya is to show what is possible. Not just that this is the story that an Asian American can tell, but that this is the kind of storytelling that can happen. A lot of times in commercial publishing, people are looked at in terms of presumptions about what the public wants. When you're somewhat blinded by a preference, whether it's conscious or unconscious for certain kinds of narratives, it's almost like you're putting blinders on your own self about the actual experiences, stories, and perspectives that are out there, and just focusing on the ones that are familiar and interesting to you.

NEELANJANA BANERJEE: Our starting point is to center things around these ideas of Asian-American, Asian diasporic voices, and innovate around those voices. We don’t have to make choices by what we think will sell, what is trendy. I'm teaching a course right now on Asian-American publishing. One of my students asked a great question: "Why is it that with Asian-American mainstream texts, it's traumatic experiences that are the ones that get promoted?” Those are the books that get published. We have to kind of sell our trauma in order to be accepted by mainstream literary organizations. I think there's this thing in the mainstream publishing industry where you're either "too ethnic," or "not ethnic enough." [Kaya Press] doesn't avoid themes that are very specific to Asian Americans, but we are able to innovate around that. One of the reasons Kaya created this space was to say, "We want to tell the stories of all kinds of people.”

NEA: What do you hope the impact of Kaya will be on audiences who are already familiar with maybe more mainstream Asian and Pacific Island literature, as well as those who haven't read any at all?

BANERJEE: The diversity of our list is so exciting. I really worked over the years to talk to educators and create a better space for educators and academics [on our website]. Oftentimes, academics and educators jump to [teaching] really big canonical work. Amy Tan, you know, or Maxine Hong Kingston, which I think is great. Teach those works, but can you also challenge the students by teaching a Kaya book? We've always pushed against this idea of “just” being Asian American and diasporic. How do we challenge people's ideas about what these things are and what they could be?”

LEE: My goal for every book, regardless of who reads it, is to have that book blow their mind a little bit. By blowing their mind, it means making them think, “Oh wow! I had no idea you could write on this level of language." That's one of the things that we pay a lot of attention to, whether it's because it's a kind of a hybrid text, a mixture of autofiction, a mixture of fact and fiction, whether it's because it's taking a story someplace that they've never really thought possible. Again, there's that idea of expanding the notion of what is possible from a reading experience from a book.

NEA: Can you identify any common elements in a manuscript that make you think, "We need to represent this author.”

BANERJEE: When you come across something that has the potential to be a Kaya Press book, it has this kind of special feel and magic to it. We say on our website that we're looking for innovative work, cutting-edge work. But that doesn't just mean experimental, avant-garde work. It's really about where are these voices coming from? What are they pushing against? What are they talking about that might be new or really interesting? It's when a text is really pushing boundaries, whether they're talking about identity, whether they're talking about language, whether they're talking about experience.

NEA: So why is it so important for readers to push themselves to have their minds blown?

BANERJEE: I think on a basic level it’s able to shift and open your brain, and help you think through new things. Sometimes we sadly come across resistance to this as a nation—we're seeing resistance to that difference. Sometimes when I am presenting our books at an event, people will be attracted to our books, and they'll come over, oftentimes a non-Asian-American person or a non-person-of-color, and they'll be like, "Wow! These books are amazing! Tell me about these books!" And I'll start with, "Well, we're an Asian diasporic press." Before I even get to the end of the sentence, more often than I would like, the person will say, "Oh, I guess not for me, then," and walk away. That is the moment where we really see the importance of our initiative, the importance of this idea that you're the diversity of the things that you read. The narratives in books will diversify your imagination, decolonize it. The work that Kaya is publishing is doing its part, even if only gets to a small percentage of the American reading public. For those people, these books are really doing the work to decolonize ideas of a certain kind of narrative on one level. But on another level, they’re also doing that really important work of decolonizing our collective imaginations, and our collective spaces of connecting and thinking about people.

LEE: What is so ridiculous is this idea that a book is not for you. Why? I think every reader of Kaya's books, or every potential reader of Kaya's books—which is the whole world of people who read books—has the ability to not just process, but digest and get a lot of nourishment from any book that we get out there.

I'm a Korean-American woman and nobody would say to me, "Oh, Moby Dick! That's not for you! You can't possibly read that, not being a white dude." The presumption somehow that a book written by a person of color is only for the people of that particular ethnicity or cultural background or whatever it is, is so ridiculous. It's always fascinating to me why and how people have that idea in their heads. I think that's part of what we're trying to work against as well by putting these books out there, by making them available. To publish something means to make it public, and then having the faith in that wider public that they will be able to understand and appreciate wherever that book went. Whether it is a truly challenging abstracted avant-garde piece, or whether it's just a completely new idea.

NEA: Neela, you mentioned that people are attracted to your books from across the room, and I know that book packaging is very important to Kaya. How did that become a part of your publishing approach?

LEE: The way that I think about editing a book is you're trying to polish the jewel in such a way that it will shine as brightly as it can. If you have a beautiful jewel, and you put it in a really ugly setting, it distracts from the beauty of the stuff that's there. I know that there's a power to the word, and that can get conveyed whether it is in a lovely font or a less lovely font, or whether someone has paid attention to margins and leading, or whether or not someone has put attention and care into what the cover looks like. But it makes it easier for a book to shine if there's been a holistic consideration of all of those elements of a book. It is an experience that we have when we're reading a book. We're not just functional machines. It's not just information input. It is an experience. So that's why it is so important that we get the covers right, and that we make sure the books are something pleasurable to own and to hold and to have.

NEA: Both of you mentioned that it's an accomplishment in and of itself to have kept this press going for over 25 years. Right now, every arts organization is struggling in a way they might not be familiar with. Do you have any advice for other literature organizations about how maybe they can keep going right now?

LEE: Having been based in New York until 2003, Kaya went through first the Asian financial crisis, which had a big impact on us for various reasons, and then we were below Canal Street when the World Trade Center happened. So this is our third big traumatic event. This is very different in many ways. 9/11 was so deeply impactful to the whole city in a very immediate and present way. This is weird, because there's nothing to look at. There are no columns of smoke, there's no endless footage on TV.

The reason why people go into publishing is because they love books. And not just that they love books, but they understand the impact that books can have. I wouldn't be doing this work if I did not think that books can actually change people's lives. Personally, my life has been expanded multiple times, and in infinite directions by the various things that I've read. There's something about that act of imagination, which is so critical to the work that we're doing.

It's important to connect to why you're doing publishing, and why it matters to you, and continue to pursue that through whatever means possible. There's something very deep and resonant about publishers and the reasons why they publish. I feel like that inner drive will continue. Who knows what the future holds in store? The economy shutting down is not something any of us have ever seen before. So it's hard to predict how you move on in that sense. But the work of writing, the work of publishing, the work of making things public, the work of sharing the wealth that exists in people's imagination is not going to stop.

NEA: Do you have any suggestions for what books people might pick up during these strange times?

BANERJEE: There's an author that I love—Vivek Shraya, and she writes the most interesting multi-genre, queer books. She has a new book out called The Subtweet, and it's about two South Asian musicians—one whose name is Neela, so that's probably why I'm into it. This is the kind of book I feel like is a great distraction at this time, but it’s also a beautiful book about South Asian female friendship. One of the things that I was especially excited about with this book is that [Shraya] actually recorded two versions of this song [as if recorded by the book’s musicians] that you can hear—the hardcover book comes with a CD. That just seems like something awesome that Kaya would be really interested in doing.

LEE: Amongst Kaya books, I would say, go for funny. So in that sense I would say So Many Olympic Exertions by Anelise Chen, would definitely is funny, and it made me laugh out loud. Or Waylaid, which was Ed Lin's first book that he published with us, which is about a 12-year-old in a seedy motel on the Jersey Shore, who's trying to deal with his sexuality. That's another funny one.

There’s also so much anti-Asian crap happening in the world. My own personal non-Kaya reading habits have tended toward reading about China, or Chinese writers. And again, a non-Kaya book that I read recently that was, again, laugh-out-loud funny to me was Mo Yan's Life and Death are Wearing Me Out. It was hilarious. I was recently listening to a presentation about someone who was talking about being afraid to go out with a mask on in New York as an Asian American. There's a very real effect that is happening that is bringing to the surface a lot of latent concerns and fears that have historically been in this country.

We published two other authors, Younghill Kang and H. T. Tsiang, who lived in an era where they could not become American citizens because people were scared of Chinese people. So I would suggest that readers go out and make a conscious and conscientious effort to try to dig into some of the authors who might give them a different perspective.