KEITH JARRETT: What I'm seeking is this music that's in the air that is ready to be played at all times, that's why I show up at a concert. That's why I do solo concerts.

When I'm out there and there's just a piano, if I can be available to that music that was not played or if I can manage to mold something that I never expected to happen to me. And that's why being in the room as in the as an audience member for a solo concert, you are actually watching the process

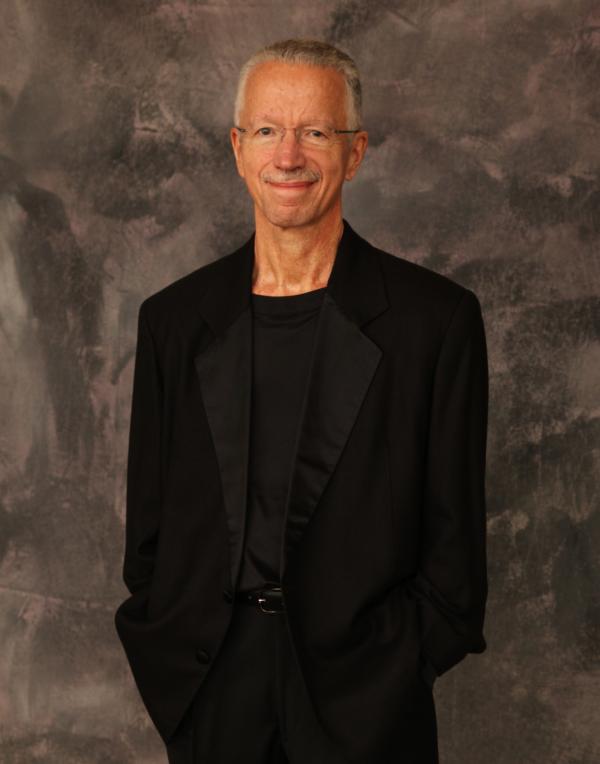

JO REED: That's 2014 NEA Jazz Master Keith Jarrett, and this is Art Works, the weekly podcast produced by the National Endowment for the Arts. I'm Josephine Reed.

Keith Jarrett is one of the most creative musicians performing today. He is a master of jazz piano known for his brilliant improvisations--although he's also written hundreds of pieces for his various jazz groups. Jarrett is also an accomplished classical musician who's composed extended works for orchestra, solo instruments, and chamber ensemble.

Keith Jarrett began playing the piano at age three, and studied classical music throughout his youth—giving his first formal recital by the time he was seven. He continued his classical studies at Boston's Berklee College of Music and with an offer to study in Paris with a renowned teacher, his career seemed set. But Keith Jarrett wanted to play jazz. He turned down the Paris offer and moved to NYC, where he began to performing with jazz greats like Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, Charles Lloyd, and Miles Davis. Keith Jarrett went on to lead his own groups including--simultaneously-- a quartet in the United States and another in Europe. Jarrett also focused on his solo improvised piano work becoming famous for walking out on stage and simply beginning to play without knowing where the music might lead. And creating extraordinarily broad and often lyrical piano performances that have been acclaimed by fans and critics alike. In 1983, Jarrett invited bassist Gary Peacock and NEA Jazz Master drummer Jack DeJohnette to record an album of improvised jazz standards. The session marked the beginning of a fruitful collaboration that has lasted over 30 years.

Although Keith Jarrett has no interest awards--they keep on coming. He’s received many---and now, he's been named an NEA Jazz Master. I spoke with Keith Jarrett in his New Jersey studio and began by asking him when Jazz first came into his life.

KEITH JARRETT: Well, it's hard to say. But I remember having a teacher in Philadelphia who didn't want me to hear other music. And I was already listening to the same thing young people in those days were listening to. Kids. I had my little 45-- record player and some of the silly songs of those days. I think the genesis to actually being a jazz player came from my desire to change notes in other people's music. So Mozart, I would be studying and playing a piece. And I'd say, "I don't really think this is the exact right voicing on for this chord."

The feeling that there should be other notes even in other people's music-- when I first heard jazz I realized that that-- it was almost, like, expected of the player to find those notes that were his.

And so it was a very natural because when I was a very young kids I was doing recitals. And on the recital program would be one thing that had my name on it. And it might be called "Jungle Piece." And it was all improvised except for possibly melodies that-- determined each section. So that was pre my hearing any jazz.

JO REED: Who did you listen to or were there any jazz players you heard-- you know, in those formative-- in your formative years that just set you back on your heels?

KEITH JARRETT: I didn't hear anybody till-- I mean I-- this is Allentown, Pennsylvania. It's really Wonder Bread, white bread kind of place. And there was almost no music coming through town. So in my formative years I heard nothing. So it took till maybe my early teens before I started to-- I remember-- malls just came into being. There were no such things as malls. And then there were malls that had little record sections. And we didn't have any money to speak of, but I-- whatever we had went to records, if I could find something. And once-- so I'd heard-- all the people you can imagine I heard. I would have heard probably Brubeck, Oscar Peterson. On-- amazing Andre Previn I thought was a jazz player too for a while.

I heard Brubeck and I remember saying to somebody, "There's more than this. There's more to do than this." It wasn't possible for me to-- to-- to actually describe what I meant, even to myself.

And then one day I think it was a mistake the buyer made. I found the White album of Ahmad Jamal. I heard Ahmad's trio and I heard the space in it. There's three guys playing, but they're, they're leaving spaces. And there's phrasing and-- that was-- contagious. And I-- I would say that that was a defining moment. And I found out driving to a gig with my trio, with Jack DeJohnette and Gary Peacock, I brought that album up somehow. It came up in conversation. And they both looked at me startled, like, "You too?" This this was a moment for them too. It was-- a transformative moment.

JO REED: You moved to New York from Boston where you had attended the Berklee College of Music. How old were you when you came?

KEITH JARRETT: Oooh. New York, Boston. ’63, ’64

JO REED: So you weren't even 20?

KEITH JARRETT. Right. Probably I wasn't. I knew I had to leave Boston 'cause I was going up on the list of commercial pianists. Not jazz pianists. All the-- all the jobs there were-- were commercial jobs. I picked up and left Boston because I knew I didn't wanna be in the commercial world at all. So driving down, I'm looking in The New York Times and the five clubs there might have been in New York all had guys like Cannonball Adderly and, you know I thought, "How am I gonna get a job in this city?"

So I patiently went to the Village Vanguard when they had jam sessions. Roland Kirk had-- was in charge of the jam sessions. But of course they wanted to have good music there, so they kept using the same guys that they'd show up and then I'd be in the corner somewhere being very shy and not knowing how to get a chance to play at all.And one day I saw the-- a tenor player taking his horn out. And I thought, "I know this guy. I know this guy." he went to Berkeley too. So I walked over to him and he said, "You're gonna play? Do you have a band?" He said, "Yeah, but we don't have some of the band but I don't have a bass player and I don't have a pianist." Sorry. And I said, "That's okay. That's okay. I can do both. It's no problem." So I played for 10 minutes with this band and Blakey was in the room somewhere. And I got hired. And that was the beginning.

JO REED: What was it like for you coming from a classical tradition. That's the way you were trained. And playing jazz. What's the difference in playing one versus playing the other?

KEITH JARRETT: Well, in the one case you're interpreting and you are correctly glued to someone else's notes. And if you're lucky, you can manage to pull off some unique thing while doing that. While playing that music. But you're not being asked to be yourself. You're not being asked to find the music yourself. So there's absolutely no-- nothing similar about those two things. If you were going to be working on a Mozart project now I would not do any improvising. You know, I wouldn't be able to mix them. Even physically the muscle groups and the techniques you're using are different.

JO REED: Even the hand motion.

KEITH JARRETT: Oh yeah. The whole angle thing, your arms, your fingers, what kind of breathing you do. If I do a solo concert sometimes I'm not breathing at all because there's so much input coming in. It's not just the music that comes in improvising. It's the way of playing it and how loud and what part of the phrase is-- should it be fading in and then where are the waves. And this is, like, being over saturated with input. And it actually comes through your entire body. And people ask me, you know, why I make the noises I make when I play. Anybody in their right mind would try to find an outlet (LAUGH) somewhere, you know, like if something's really happening the passion just takes over.

JO REED: What inspired you to begin evening long, solo improvised piano concerts?

KEITH JARRETT: Insanity?

JO REED: Yeah. It's kind of like jumpin' off a cliff, isn't it?

KEITH JARRETT: Yeah, it's insane. And when I used to teach a little bit some of these guys would say, you know, "I wanna do what you do." And I say, "Okay. Forget it." No-- nobody should do what I do. Even I shouldn't do it. I've been called. I mean as far as I'm concerned, if you're two and you're picking out melodies from songs that are playing on the radio, yeah, you should probably look for a piano teacher. And after not very long I knew this was what I was meant to do.

JO REED: There wasn't a point, I don't know when you were 12 or something, where you pushed away from music?

KEITH JARRETT: No. When I got my first piano there was an old upright that happened to be in the house. That's the only reason that I could pick out the melodies. And when I finally got my first piano, which I have trailed. I know exactly where it is. It still lives. I slept under it you know, like I got up for school and the first thing I did was play it and do some practicing. And then I'd go to school.

JO REED: What you do on that stage is you take the audience through a process of creating. Is that fair?

KEITH JARRETT: That's fair. Yeah. I actually need the audience to help me find a new focus. I mean I'm looking for new music each time.

Music up and hot

So in a very correct way, these are like commissioned work for every particular audience I ever played. So whatever, a thousand or so solo concerts may have existed of course I have to do my work and I have to be in the right state of mind and everything. But truly I am blank walking out. I'm a receptor. And what I'm receiving is things like how concentrated are-- are they?

I often know what they wanna hear after a certain amount of times you-- you can almost tell what they came for. And very often I'll go in the opposite direction. I think shock is very important.

JO REED: I know it's difficult to talk about, but what happens once the solo piece is in motion, so to speak?

KEITH JARRETT: Wow. I have no idea. It's a total mystery to me.

Music up and hot

If I remain the listener and not think I'm the player, if I remain the listener and not control the thing, something happens. I mean on-- the Rio release was not so long ago. And I can't explain why I did what I did anywhere in that concert, but some of the time I'm walking out on stage and I'm playing a definitive A minor chord or an F major chord. When I played that chord, which was the first chord of the second set, I think, I had no concept of what was coming next. Now if I go “oh gee” I don’t know what’s coming next, that's the wrong thing that's going on. But my hands and my listening found that there was something in this chord that led to the next note. It's like my body knows exactly what to do. It's just like my left hand knows how to play. And if I tell it what to play I'm stopping it. Not only-- not only am I stopping it, but I'm stopping it from playing something better than I can think of. that's the reason I'm still playing concerts. I'm too curious.

JO REED: That's kind of be here now cubed. No?

KEITH JARRETT: Yes.

JO REED: And your focus is so extraordinary. I mean the amount of energy that focus must take.

KEITH JARRETT: Yeah. The focus is debilitating. I mean, it's not so much that I come off the stage wiped out from any musical thing. It's it's the synapses that have been used and the speed they've been firing at are beyond my own comprehension. I don't have a way of explaining it. If I did, I would explain it.

JO REED: 04:32:53:00 Do you have routines, Keith, that help you prepare before a solo concert?

KEITH JARRETT: The routine is never to have a routine. That's my routine. Sometimes I say, "Oh, I need a couple minutes." But that's about it.

JO REED: It's interesting for somebody who's known so well for his solo work, you also are a great collaborator. And Manfred Eicher, your producer, is-- this is one of the great musical collaborations.

KEITH JARRETT: I think he's recorded more than any other producer, single producer. He's recorded more and released more CDs than any single producer. But even if that's not quite the case, yes, I don't know of another example of a producer and an artist

I mean he's an artist. He's not just a producer.

His ears are better than any other producer's ears that I've worked with and anybody I ever heard about. But he and I work together well because we're well rounded. We are not, like, doing the jazz thing or doing the classical thing. If I were a producer I'd probably be somewhat like Manfred. If he were a player, he would possibly be somebody who isn't satisfied with just one direction.

JO REED: Your other great collaboration is with your trio, which we mentioned briefly earlier. Gary Peacock and Jack DeJohnette. How did that trio come together?

KEITH JARRETT: It was actually Manfred's idea. The trio idea was my idea, but I was not sure who to use. And I was reminded that I had done an album with Gary Peacock and Jack was the drummer. And that was before the trio started the standards thing. So Manfred said, "Well, why don't you use Gary? You know, and Jack. But what was even stranger was that my concept was to play standards that already probably knew because it occurred to me that it's the side men that have the freedom. The leader's always the leader. I wanted to be my own sideman too. And I thought they would understand this because when you're a leader you have to, like, tell everybody else what you want from them. What about if we have the feeling of being a side man. That there's no leader. And the only way to do that would be either totally free playing or music we already know. So I thought, "Okay, I have these two wonderful players. They're gonna know what to do." Just like I would if they started to play something. And so that's how it works.

The principle in this trio has been the same from 1983 to 30 years later. It's been exactly the same.

JO REED: So you get on the stage. You don't have a song list--

KEITH JARRETT: No.

JO REED: per se.

KEITH JARRETT: No, I have-- pieces of paper on the piano. If you saw over the years they're in the same order all the time. I barely refer to them. When I'm in a bind and I really don't have an idea I might look at the list for a second and whatever. The 300 or 400 songs we've played. They just developed. Sometimes at sound checks.

JO REED: You were a leader with in other circumstances, as you said. And I'm thinking about the American Quartet with Charlie Haden and Paul Motian and Dewey Redmond. Can you describe a little bit what being a leader meant?

KEITH JARRETT: If you are a good leader then you are also a psychologist of some kind. And if you know the potential of the players, if you're lucky or smart-- like Miles is an example of being smart, most of his career he had people playing with him who already knew something. And he would just have to give them a little tiny bit of a hint of about what-- the material is about.

With the quartet, I was writing all the music for Dewey and Paul and Charlie. And it was written for them. So it's a kind of getting to know the player so well that the music you write you're hearing them in your head so you're writing for them. And for me.

So there'd be pieces where like, Dewey did not like to play on chords very much. So I'd make it so that there would be a section when Dewey's solo would be there that either I'd go to percussion and Charlie, being an old Ornette staple Charlie knew exactly what to do in most situations. So Dewey could get to play free if he didn't wanna play chords.

On the night that Don Byas the day Don Byas died I didn't know he died. He was a tenor player. Dewey and the quartet were the Vanguard. And Dewey on a tune that had fairly complex harmonies Dewey played just all over and through these chords. And I-- I never heard him play like that before. And after tthe set I said, "Okay, Dewey, what happened just now?" And he said, "Oh, Don Byas died today and I was thinking about him." And I said, "Oh," to myself. "See he-- he can do all this things he doesn't know he can do." He was, like, channeling somebody else's playing.

JO REED: Fascinating. When you played with Miles Davis you were playing electric piano. Can you talk about how you hooked up with Miles Davis?

KEITH JARRETT: Let's see. There was the fact that he would come to the clubs we were playing in, the trio. And I'd walk past him and he'd say, "You're playing the wrong instrument." And I'd say, "What do you--" I know exactly what he means. I-- you know, I can't get what I really hear out of the piano. He's the first person that ever, you know, actually said that in the most terse way and I understood what he meant.

He brought his whole band to hear the trio that I had with two European players in Paris. So he was interested in what we were doing. And in that club he said, "How do you play from nothin'?" And I said, "I don't know. I just do it.“

And then I had heard his band, of course, a lot of times. And it was getting to be, like I felt like he needed something new. And I-- it seemed like he felt that way too. So at some point he just said anytime I feel like it, I should show up. And this was when he had Chick.

JO REED: Chick Correa?

KEITH JARRETT: Yeah. Chick Correa. So we had an electronic instrument there. The organ. (LAUGH) A piece of you know. Terrible metallic nothingness.

And Chick was on the other side of the stage. And it was nice to play with another keyboard player in the band. The only other time I did that was also with Chick when we played Mozart together. Jack was in the band and I had known Jack's-- Jack and I kept ending up in the same bands. And then Miles said, "Well, which instrument do you wanna play?" And I said "Both?"

Music up and hot

'Cause I hate-- you know, I hate both of them equally, but maybe if they're together something'll be different. Like, the organ and piano might sound different together. I can get vibrato out of one of them and not the other one. Or I don't know. so he just started bringing both-- both keyboard instruments.

JO REED: And how were they set up?

KEITH JARRETT: In a V.

JO REED: How old were you then? Just a ballpark.

KEITH JARRETT: Must have been '70 or '71.

JO REED: So you were young. You were 25?

KEITH JARRETT: that was a young period in your life. Was that a formative even though you were playing on electric instruments, was it still a formative relationship?

KEITH JARRETT: Well, here's what happened. I was under the strong impression, which turned out to be correct, that Miles wanted more funkiness. And he was already using electric instruments and he was already using wah wah pedal on his trumpet. So as far as I was concerned, if I was gonna ever contribute anything to his band it would have to be on his terms as far as the instruments were concerned.

JO REED: He knew I hated them. I mean you know. But it piano would have stuck out like a sore thumb in with everything else being louder, basically.

You were also playing classical music. You hadn't stopped--

KEITH JARRETT: All along.

JO REED: Yeah. But quite famously you wouldn't compose a cond-- a cadenza. You wouldn't-- you wouldn't improvise one. Can you explain your thinking behind that?

KEITH JARRETT: Yeah, it's too short an improvised moment. (LAUGH) No, actually, for me what it would mean would be that I'd have to develop this cadenza in the style of the piece, somehow. And I didn't wanna do that. I-- I didn't-- I don't wanna do that on demand. That's like, "Okay, play something from the 19th century. Improvise something." I don't wanna be a period improviser." I just wanna be in the moment at the moment doing what seems right with no music on the left, no music on the right. That's basically-- that's-- that's my--

JO REED: 05:06:50:00 You don't wanna create the thing that takes you from point A to point B?

KEITH JARRETT: Right. There's no points.

JO REED: You made a decision to step away from performing classical music.

KEITH JARRETT: Yes.

JO REED: Why did you do that?

KEITH JARRETT: Because the classical world almost created a nervous breakdown for me. Starting at bar 163 or whatever bar it is in the middle of a Samuel Barber piano concerto that's at that point you're supposed to be feeling passionately screaming at something or, you know, very much into the piano.

I could never-- I could never do this. If I had two careers in two eras, I'd wanna be in like, in the '30s when editing was not so easy or-- or even possible. And like Schnabel, Artur Schnabel, who was a Beethoven player. He has said what I wished I had thought of saying, which is, "I don't like doing another take just because I played a wrong note. If I do another take, it might be better but it won't be as good." (LAUGH) And I love this guy. He's the world's most honored Beethoven player. And you can hear every now and then that he's a human being and he's just hit the wrong note. And so what?

But the classical world, it's so different than the jazz world. The classical world is so uptight and so speedy. They're worried about their playing. I mean they're worried-- they have to-- I did a project with various people and they're always in here practicing, practicing. The same piece, same piece, same piece. I mean it's like what I think about Broadway shows. Would I wanna be saying the same lines every night all the time? And then practice them and practice them? And then would I wanna be with a bunch of people who have just done the same thing and they're worried for their own reasons. And everybody's on stage being, like, nervous wrecks.

So jazz is not like that when it's good. I mean when things are right. Actually, I wish jazz players would listen to other music more and I wish classical players would participating-- let somebody take the music away. See what happens.

If that makes you angry and psychotic, okay, put the music back. But I think there's not enough of a mix. And I'm not talking about-- fusion stuff. Somebody once said, "Every word you read in a book stays with you." So I mean if you-- if you listen to enough kinds of music, that starts something completely new and chemically-- happening to you. Especially if it's strong music.

JO REED: You also compose classical music.

KEITH JARRETT: Yeah.

JO REED: Less so now.

KEITH JARRETT: Less so after chronic fatigue syndrome, when I made a kind of resolution to be an improviser until I had to stop.

JO REED: Talk a little bit about that illness and that was a horrible, horrible thing that happened. That was in the mid-'90s?

KEITH JARRETT: Yeah. You just explained it.

JO REED: It sucked--

KEITH JARRETT: Chronic fatigue sucks. (LAUGHTER) It's-- the-- the best explanation of it that I've heard is it's like the last four months in an AIDS patient's life. But it goes on forever. But I found a doctor who was having success. And I stuck with him. Followed his protocol.

JO REED: How long did you not play?

KEITH JARRETT: Well, you know, it was a gradual trying to play again. I had a rehearsal with the trio in the studio maybe a year and a half after I got sick. And had a relapse immediately.

I think it took another six months before I could say I trusted myself. So-- so let's say two years. Two years of being totally absent from the scene in a way.

JO REED: Do you think a CD, for example, of your solo concerts or-- of your work with the trio, do you think it gives the listener something close to the experience of actually being in that hall with you?

KEITH JARRETT: Can I just say no to that? (LAUGHTER) No. A CD is not close to the experience of being in the hall.

JO REED: What does the CD give you then?

KEITH JARRETT: The CD can give you---the ones I decide that should come out are ones I also decide as a listener. What is happening to me while I listen to it? If it's enough of what was going on, and if-- you know, if there's enough that it should come out and other people should hear it, then I know that.

But there're a tremendous amount of concerts that are good but they were besides the sound problems, besides the fact that not-- not every recording can-- can be released 'cause of other things, or the pianos, there is this factor of how much of the event can the listener to a CD can they grasp what just happened? Can they grasp it? Because it isn't in the moment anymore. It's on the CD. There's some ways of recording and there's some kinds of music you could record that don't have that problem. But live? It's almost always live when I do solo. It's a different thing by far to be in the hall.

JO REED: And let me ask you in closing…This was you quoting somebody. "Don't follow in the footsteps of the wise. Seek what they have sought."

KEITH JARRETT: Oh yeah.

JO REED: And I'm just wondering what have you sought?

KEITH JARRETT: What I'm seeking is that. This music that's in the air that is ready to be played at all times, that's why I show up at a concert. That's why I do solo concerts in particular because the trio has a manifesto. You know, we know what we can do and can't do and drums are drums and bass is bass.

But when I'm out there and there's just a piano, if I can be available to that music that was not played or if I can manage to mold something that I never expected to happen to me and that's the right phrase to use. Happen to me. And that's why being in the room as an audience member for a solo concert, you are actually watching the process even if your eyes are closed some of the time. You're seeing what I'm going through and hearing the sounds that come out. So that takes you much closer if you are a sensitive person. If you are paying attention. And not coughing. (LAUGHTER)

JO REED: Or shifting

KEITH JARRETT: Or using your cell phone.

JO REED: Keith, thank you. I really appreciate it. And congratulations on being named a 2014 NEA Jazz Master. I think we were all very touched that you agreed to accept this award because you’re not interested in awards, typically.

KEITH JARRETT: Oh, you knew that.

JO REED: We did. So we rolled the dice with that one.

Well, there was a time in the beginning that I decided I don't do these things and I'm gonna have to say, "No, I don't do this." And then I asked Steve Cloud if he could look up the people who already won the award. And I realized how many of those people were people I heard when I was young who you know, opened the doors for the music for me. So I thought-- I can't not be in their company. So basically I still feel the same way about awards except I've also said to people, "Oh well, if someone's gonna give me an award, I deserve it." (LAUGH)

JO REED: Well, there you go.

That was 2014 Jazz Master Keith Jarrett. Keith Jarrett and the other 2014 Jazz Masters will be honored with a concert and ceremony on January 13 at JALC in New York City. The NEA is webcasting the event live---go to arts.gov for details.

You've been listening to Artworks produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. Adam Kampe is the musical supervisor.

The Art Works podcast is posted every Thursday at Arts.gov. You can subscribe to Art Works at iTunes U--just click on the iTunes link on our podcast page.

Next week, we go backstage and find out how the SAG Award Show is put together. To find out how art works in communities across the country, keep checking the Art Works blog, or follow us @NEAARTS on Twitter. For the National Endowment for the Arts, I'm Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.

MUSIC CREDITS

Excerpt of "Ahmad’s Blues" composed and performed by Ahmad Jamal from the album, Portfolio of Ahmad Jamal, used courtesy of Universal Music Group, Inc.

used by permission of Warner-Tamarlane Publishing Corp [BMI].

Excerpt of "God Bless the Child" composed by Billie Holiday and Arthur Herzog Jr. and performed by The Keith Jarrett Trio from the album, Standards, Vol. 1, used courtesy of ECM Records.

used by permission of Edward B. Marks Music Company c/o Carlin America Inc. [BMI].

Excerpt of "Rio Part I", "Rio Part XV" composed and performed by Keith Jarrett from the album, Rio, used courtesy of ECM Records.

used by permission of Kundalini Music c/o American Mechanical Rights Agency, Inc. [BMI].

Excerpt of "No Moon At All" composed by David Mann and Redd Evans and performed by Keith Jarrett and Charlie Haden, from the album, Jasmine, used courtesy of ECM Records.

used by permission of Music Sales Corporation and RYTVOC INC c/o MPL Communications [ASCAP].

Excerpt of "Honky Tonk", composed by Miles Davis, used courtesy of Sony Music Entertainment and Universal Music Publishing Group and East St. Louis Music, Inc