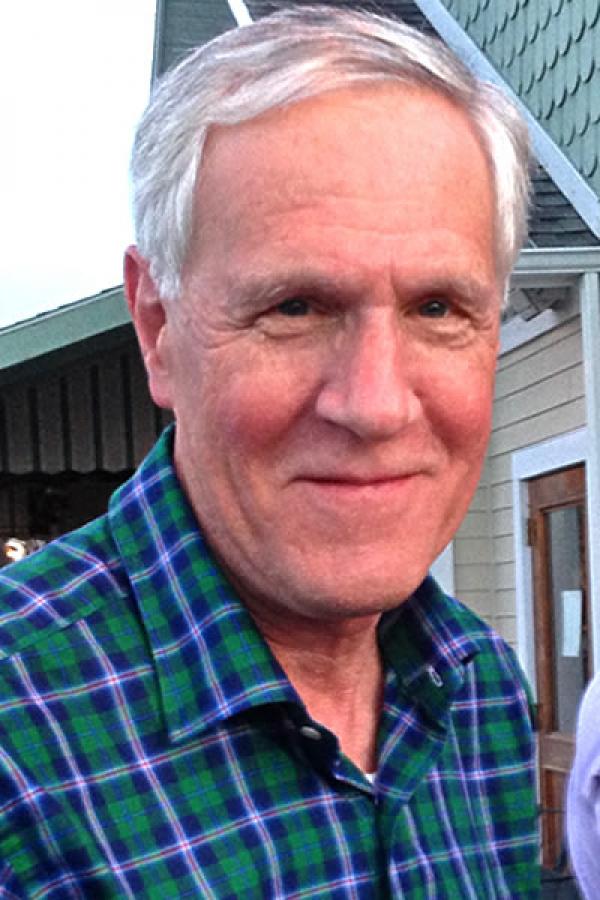

David Dollenmayer

Photo by Linda Pape

Bio

David Dollenmayer has translated works by Rolf Bauerdick, Bertolt Brecht, Elias and Veza Canetti, Peter Stephan Jungk, Michael Kleeberg, Michael Köhlmeier, Perikles Monioudis, Anna Mitgutsch, Mietek Pemper, Moses Rosenkranz, and Hansjörg Schertenlei. He is currently at work on a translation of Martin Walser's A Gushing Fountain. His translations of reviews by the art historian Willibald Sauerländer appear frequently in the New York Review of Books and a translation of Sauerländer's The Catholic Rubens: Saints and Martyrs is forthcoming from the Getty Foundation. Dollenmayer is the recipient of the 2008 Helen and Kurt Wolff Translator’s Prize (for Moses Rosenkranz's Childhood) and the 2010 Translation Prize of the Austrian Cultural Forum in New York (for Michael Köhlmeier's Idyll with Drowning Dog, forthcoming from Ariadne Press).

Translator's Statement

We all owe a great debt of gratitude to the National Endowment for the Arts for supporting the vital activity of translation, which connects us to a vast and otherwise inaccessible world. Without translations I'd have to do without the Bible, Homer, Dante, and Dostoevsky—just for starters. Rather late in a career spent teaching German language and literature, I stumbled upon the enormous pleasure of making great novels such as Michael Kleeberg's A Garden in the North available to readers who don't happen to know German. Close reading of texts was at the core of my interest as a scholar and teacher and translation feels like an extension of that – the closest of close readings. My translation philosophy (if that isn't too grand a word for it) is straightforward and consists of three principles: 1) account for every word of the original, 2) strive to find the English equivalent of the author's voice, and 3) strive to make the work sound like it was originally written in English. Another way to put the third principle is that I do not subscribe to a theory that asks the translator to make readers aware that they are reading a translated work. Like it or not, the translator should be invisible, or at least inaudible. Except to repeat a loud THANK YOU to the NEA, and to Congress for continuing to fund it.

Excerpt from A Garden in the North by Michael Kleeberg

[translated from the German]

A Turkish girl was perched behind the reception desk. She was pretty and shy. The room upstairs smelled like deodorizer and varnished veneer. I got right into the shower. No soap, no bath gel, no shampoo. I sat down naked on the bed, picked up the phone, and dialed O. The Turkish desk girl was unfazed: "You must come down and I give them to you. Oh, and here there’s a man. He wants to speak to you."

"There’s a man who wants to speak with me?"

"Yes.”

She said nothing more, so I got dressed again and went back downstairs. The girl handed me a wrapped bar of soap and a tube of shower gel that could also be used as shampoo, and gestured toward the door with her eyes. There stood the blond driver of the Golf convertible. He was taller than me, about 6’2”, and wore his hair short in front and long in back. He had on a three-quarter length belted black leather jacket and gray pants with a crease. He stared at me out of small, light blue eyes.

The boy drew himself up to the full height of his perhaps twenty-two years.

"When you parked you hit the bumper of the person behind you. I saw it. And you didn’t even look to see if you’d done any damage," he said, menacingly.

Not "Good evening" or "Excuse me" or "May I speak with you for a moment?" I was about to answer when it occurred to me that he’d only seen the plates on the Renault and probably thought I was French.

What was there to say? That the car behind me was a 1969 Commodore coupe that only the rust was still holding together? That I had touched the bumper, but less roughly than my interlocutor probably pinched his girlfriend’s nipples on a Saturday night? That he surely wouldn’t have made this much fuss about someone setting fire to a shelter for asylum seekers? In his years abroad, the exile both discovers and invents good reasons for despising his homeland, for considering it hopeless, especially when its name is Germany, and after all, this boy was only confirming what I was already convinced of. Perhaps my compulsive desire to collect evidence against my country of origin had something of the aggressive insecurity of a soldier who has never been at the front. I belonged to a generation who were sure we would have behaved better than our parents. Whatever the reason, I suddenly saw in this young man, so eager to protect German streets and German Opels, the epitome of a Nazi.

"What are you, some kind of SS guard? Mind your own damn business!"

The young man and the Turkish girl both stared at me dumbfounded.

"So you refuse to come outside with me to check for damage?"

I twirled my index finger toward my temple, turned on my heel, and climbed the stairs to my room.

"You haven’t heard the last of this!" he called after me.

About Michael Kleeberg

Michael Kleeberg is widely recognized as one of Germany's leading novelists. In A Garden in the North he exploits elements from popular fantasy writing to connect two narrative and temporal levels: the post-reunification present and the problematic German past from the 1880s to the 1930s. Kleeberg's first-person narrator Albert Klein reimagines historic figures such as Richard Wagner and Martin Heidegger not as an anti-Semite and a Nazi sympathizer but as creators of elegant, graceful, accessible, and unencumbered works. He also writes one of the greatest love stories in post-war German fiction while coming to terms with his own alienation from his native land.