Frederika Randall

Photo courtesy of Frederika Randall

Photo courtesy of Frederika Randall

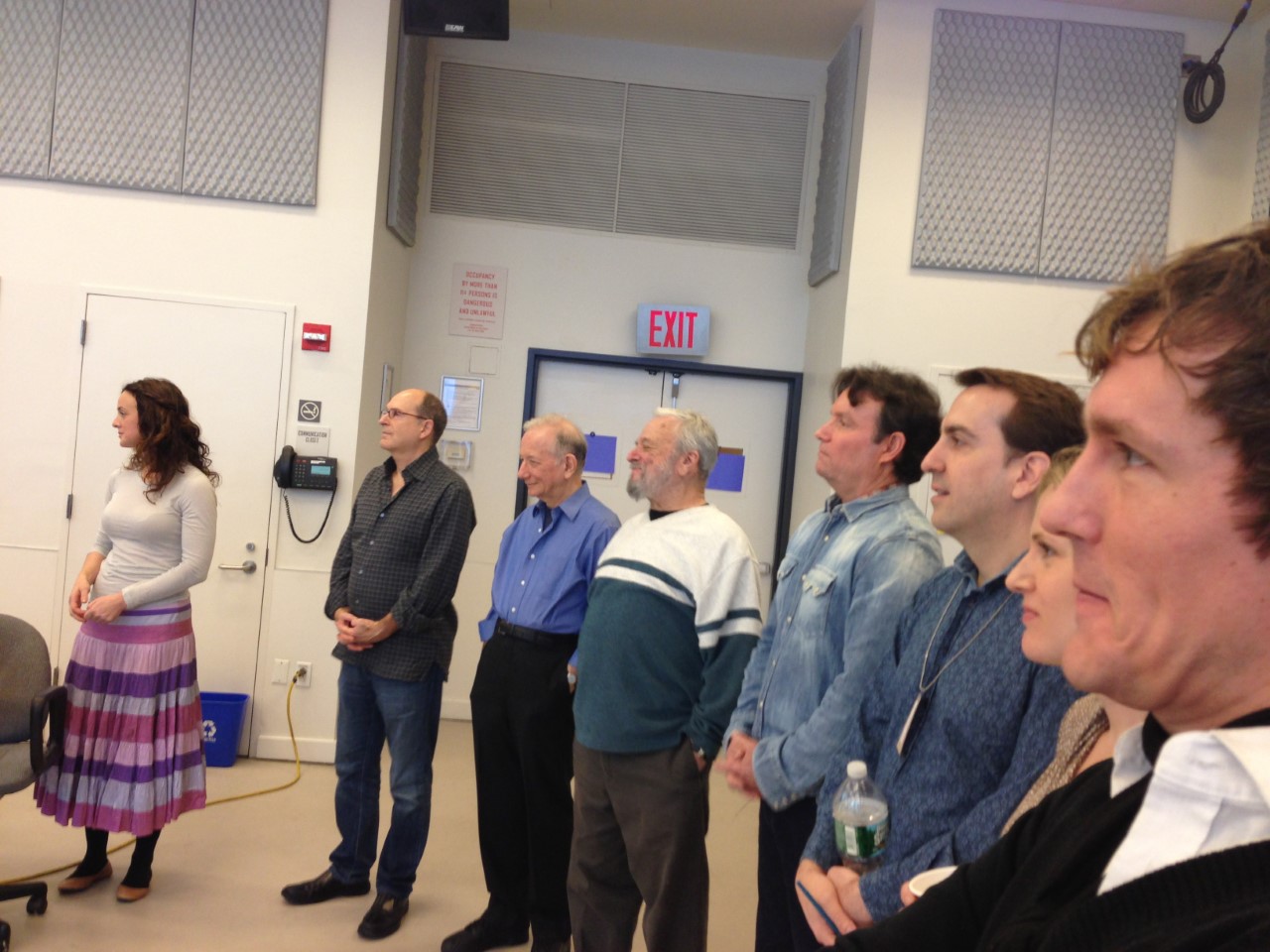

During the Classic Stage Company’s production of his musical Passions, Stephen Sondheim (middle) takes in the first rehearsal. Photo by Greg Reiner

Music Credit: NY composed and performed by Kosta T from the cd Soul Sand, used courtesy of the Free Music Archive

Kelly Church: I come from the largest black ash family in Michigan to have continuously weave baskets and have a lot of extended family who still do it. I like to have my baskets to also include messages for people educating them about why the basket’s important to us, why the tree’s important to us, all of those aspects.

Jo Reed: That’s 2018 National Heritage Fellow, black ash basket maker Kelly Church, and this is “Art Works,” the weekly podcast produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. I’m Josephine Reed.

Today, we’re revisiting my interview with Kelly Church an extraordinarily accomplished black ash weaver—making baskets that range from utilitarian to ornamental—often sculptural and in vivid colors. Her baskets are visual testimony that traditional art also has the wings to fly into the unexplored. Kelly Church is deeply committed to the traditional ways of basket-making—from selecting and harvesting a black ash tree to stripping the bark, to pounding the tree rings, and creating the ribbons of smooth ash that she weaves into baskets. It’s labor intensive, communal, and steeped with history and ritual. And Kelly works to keep this tradition alive and vibrant. Whether it’s teaching children, holding gatherings for weavers or lecturing at colleges, Kelly combines her artistry and passion with her commitment to education about this ancient tradition. And this is timely: black ash basketmaking is under increased pressure because an invasive species, the emerald ash borer is killing ash trees throughout Michigan. Kelly is in forefront of the battle against emerald ash borer—spreading the word about the infestation, collecting ash tree seeds and documenting the process of ash harvesting and basket-making for future generation. And artist that she is—she includes messages about these threats into her weaving. Here’s my 2018 interview with black ash basket maker Kelly Church.

Kelly Church: I am Anishinaabe from Michigan, and Anishinaabe is the Potawatomi, Ottawa and Chippewa of Michigan. So I belong to the Gun Lake Potawatomi Band, and I’m a descendent of the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa & Chippewa. I come from an unbroken line of weavers, so we’re not really sure where they started, but we do have a picture from 1919 of our family weaving. So with that picture I’m fifth generation. My daughter’s sixth generation. So it’s just something that has been sustained in our family.

Jo Reed: How did you learn?

Kelly Church: I learned from my father. I was raised with my mother and, you know, saw my father on the weekends and, you know, the visitations and things, and so I grew up seeing the baskets made with the extended family and such but wasn’t really interested at that time in baskets, and when I got into my twenties and I was older I started taking care of my grandparents. My grandfather needed help at that time, and so by taking care of him is really how I got into black ash basketry. When people would mow the law or bring food, my grandfather would say, “We need to make that person a basket.” Making a basket, to him, was his best way of saying “Thank you” to somebody, so I went to my dad one day and said, “Dad, Grandpa wants to make baskets so we can give them away as thank you gifts. Can you take me to get a tree?” My dad was like, “Let’s get in a car,” and we left within two minutes. You know, most people would say, “Okay. Let’s do it Saturday at two o’clock or so.” Like, literally, I asked and we left, and we drove about a hour and a half up north where he knew some black ash trees where, which are our basket trees, and he harvested it. He pounded it, split it, scrap it, showed me how to do everything. He made it look so easy. So that day when my daughter got home from school at three o’clock I told her, “Hey, come here. I’m going to show you something,” and I couldn’t do anything, and then I learned that it was something that I really needed to work at, to persevere, learn, practice, and sustain the tradition in our family.

Jo Reed: Will you give me an example of what the baskets are used for?

Kelly Church: The baskets are used for so many things. So originally they were utilitarian baskets. They would’ve used them to carry our babies. Fishing creels were made from black ash. Gathering baskets. As non-native people moved in and they started going to the market to buy things, they would make market baskets. So pretty much everything that you had a use for we could make a basket for.

Jo Reed: Weren’t they also given to mark big occasions in people’s lives, like the birth of a child?

Kelly Church: Yes, yeah, definitely. There are wedding baskets that are made for weddings, ceremonial baskets that are made. We have corn winnowing baskets. All different kinds, and then you’ll have a ceremony for harvesting the corn. You will have the baskets which winnow the corn. So yes. They’re really important in marriages. People will exchange baskets filled with things that they promise to each other, and beautiful things like that, so yes, our baskets were a integral part of our life.

Jo Reed: Now, you gave a sense of what the process was like from living tree to basket, but can you walk me through that more slowly?

Kelly Church: Yes. Black ash trees grow in the swamps. So that is the only place you can acquire the trees. They only grow in the Northeast United States and Southeastern Canada. When I go into the woods I’m looking for a tree that has straight bark and the growth rings need to be about the thickness of a nickel. That’s the ideal basket tree. So when we find these characteristics in a tree, we will harvest it, and the first thing we’ll do is we’ll offer tobacco, and that’s giving thanks before we take that tree, for all of the keepers of the forest that have kept these trees good for us and also for the ancestors for passing on all of these wonderful teachings to us. And once we harvest that tree, because we are in the swamp, like I said, we have to put it on our shoulders and walk out of the woods, and when we get to our car we’ll drive home, and then we’ll pound on it with the back side of an axe. So the first thing, you have to imagine a log like six foot in length, maybe 8 to 10 inches in diameter, and we’ll debark the log from end to end, and we’ll do that with a hatchet or an axe, and then we will begin to pound on that with the back side of a very old axe.

Jo Reed: Why does it have to be very old?

Kelly Church: Because new axes have those sharp edges and they can ruin your wood. So if we can find one that nobody has any use for anymore, it’s very useful for us.

Jo Reed: Oh, so it’s already smooth and worn down.

Kelly Church: Yes. An axe is about a inch wide, so as you pound, you have to overlap every pound. So you’re actually pounding about a half inch down that six-foot log at a time, and you have to pound as hard as you’re chopping wood. So it’s a really laborious job, but when you are pounding, it separates the fibers in between the growth rings, and each growth ring will begin to pop up. So with the men in the family that are the great pounders that we have, they can usually get about 8 to 10 growth rings at a time from pounding. If I do it alone, maybe it’s five, because I can’t pound as hard, and so once the growth rings come up and they pop up, we separate each growth ring from each other, and then I will take this growth ring, which is about the thickness of a nickel, and I will score across it with a knife until it is just barely peeling apart, and then I will separate that, which-- and you kind of peel it like a banana from end to end, and so the outside of this growth ring is very rough. There’s nothing smooth about it. It’s course, and once you score that and peel it apart, on the inside it’s very smooth, it’s silky, it’s beautiful, and that’s where we get all of our basket weaving material from.

Jo Reed: And do you soak it then? What’s the next step?

Kelly Church: If we get it green from the forest we can pretty much pound, split and scrape and do everything right away, but water is very useful for us, because it does grow in the wetlands. So I can pound these strips off and I could keep them somewhere-- I’ve actually put some in storage for three years once when I moved and forgot about them, and you can rewet them and you can use them again.

Jo Reed: So the process of making the strips of wood that you actually weave, it’s like an art unto itself.

Kelly Church: It is. It’s about 75 percent of the process that we actually do, so when someone asks me, you know, “How long did it take you to weave that basket?” the basket part might only be 5 hours, 10 hours, 15 hours, but it’s the process leading up to that that really took the time.

Jo Reed: It also seems, given the nature of it, that it’s something very difficult to do on your own.

Kelly Church: Definitely. And so that’s what I love about black ash teachings. They teach you to work together. They teach you community, sharing. You know, all of these great teachings go into black ash. Patience. That’s another great teaching that we all have. Yeah, you couldn’t do it alone. You wouldn’t want to harvest alone. You could have the tree fall on you. Pounding you would get way too tired. So it is a wonderful thing that brings all of our communities together and families together.

Jo Reed: You talk about memory a lot. How does memory factor into this?

Kelly Church: I love to say blood memory. Blood memory exists, and so when I work with people that I know have had ancestors in their family that were weavers, you can almost see that blood memory just coming out in them. It can take a person, you know, maybe up to a month to learn how to split a growth ring, and occasionally I’ll work with children who I know their grandmothers were weavers or such and they just catch on really quick, and I myself believe it is the blood memory in all of our children, and so today we still, even though we are losing our trees very steadily to the emerald ash borer, we like to hold black ash gatherings and keep on making what we call black ash memories.

Jo Reed: When you’re weaving, is that a time for storytelling or talking about the people who have come before, your ancestors, elders?

Kelly Church: Yes. When we hold basket gatherings, that’s one of the best parts about it too, is hearing people say, “You know, I remember my grandmother doing this and I remember my uncle pounding,” and these stories do come out, and then people are sharing these stories. They’re making new stories too as we’re weaving, because, you know, there might be something funny that happens. So those will be stories that would be told in, you know, 10 or 20 years. “I remember when we had a gathering--” and this happened. So there’s a lot of knowledge to be shared during that time with, “My grandmother used to weave like this. This is the kind of basket she made,” and then there’s also just a lot of just good memories for everyone to have, that they probably don’t sit around and reminisce about as much as when they are actually with the material and weaving.

Jo Reed: What about your own weaving? What is it that you like to weave best?

Kelly Church: Coming from a large basket family, my daughter and I early on, we would always make baskets just like everybody else, because there’s family styles and there’s also traditional utilitarian baskets, and so early on we would look and we wanted people not to say, “This is a Church basket.” We wanted them to say, “This is a Kelly basket,” or “a Cherish basket.” That’s my daughter’s name. And so early on we started just coming up with different concepts and ideas, and what we found is you can make anything out of black ash. So my daughter, she wove the body of a woman, and so she is well-known for weaving her body baskets of pregnant women, and I make baskets, fashion them into top hats, and the top hats represent our treaties in Michigan. We were big into fur trading and we had top hats early on, our native people did, and so I’ll use these top hats to share the treaties that we have signed in the area, which give us our rights to harvest, which are very important to our people, and one basket that I make I call the fibergé egg, because it’s made out of fiber. So it’s not Fabergé, it is fibergé, and with this I do it in a green color and I weave copper into it, and so it will draw the viewers in when they come to see this, and then they’ll open it up and it will have a bug inside, and really that is to draw them in with the beauty of the product, but then I want to share the story with them of the emerald ash borer, because the emerald ash borer’s been killing all of the trees in the United States, and it’s the trees that we use, the black ash trees, and so the emerald ash borer’s brilliant green. It has a copper belly, and so that’s why I use those colors in that basket.

Jo Reed: Aw, it’s such a beautiful bug, even if it’s deadly.

Kelly Church: It is a beautiful bug. <laughs> Yes.

Jo Reed: Well, I was going to talk about this later, but I’m certainly happy to talk about it now. The emerald ash borer is an insect. It’s not native to the United States. It came over from Asia, and it’s destroying the ash trees.

Kelly Church: Yes. The emerald ash borer is about the size of Lincoln’s head on a penny. So it’s a very small bug, but it is very devastating to the ash tree. In Michigan alone we’ve lost definitely over 500 million ash trees already. The mitten of Michigan, the lower peninsula, is almost decimated of them. So there are some trees but pretty much, you know, the emerald ash borer will eat anything from a inch big to, you know, 20 inch in diameter, young to old trees. So at this time, we have lost over 500 million. There’s 803 million that have been predicted to be lost in Michigan. Not black ash particularly, but all brands of ash trees, but now the bug is in over 30 states, 2 provinces in Canada, and it’s just so small to detect that you really don’t know you have it until it’s about its second or third year in and it can kill the tree in about five, so...

Jo Reed: Is there any way to stop it?

Kelly Church: There really isn’t any way to stop it. You just have to be aware of it. So collecting seeds is going to be the most important thing that everyone can do to bring back these trees and to, you know, have them regrow again in the United States. It is a indigenous native tree to the United States, so it’s something that we would want to keep here.

Jo Reed: You’ve said you think 99 percent of the black ash trees will be lost?

Kelly Church: Yes. Definitely. The emerald ash borer actually prefers the black ash tree, so it will eat the black ash before it eats white ash or green ash, and so the UDSA predicts 99 percent of the trees will be gone, but what I like to say is, “Listen, there’s one percent living,” so if, you know, I like to see everything as the glass is half full instead of empty, so I like to think that we will be able to sustain this by collecting seeds, by teaching our youth now how to harvest trees. That’s one of the most important aspects, as I was saying, it’s about 75 percent of all the work we do, harvesting, and so that’s a very critical point of this whole juncture, that we as adult harvesters and weavers, are all coming to recognize that we might miss a whole generation or two of harvesters, and then how do you teach them after the trees are gone? So we’ve been coming up with other ways to do this, such as videotaping step by step into the forest. I had a videographer tell me I have the most boring video ever made, but if you watch my video from beginning until end you would know where to go to look for trees, what kind of soil you have to look in, what the trees look like, what a black ash stand looks like, what a good tree looks like, how to pound it, split it, scrape it. So I did one of those really boring, every step, every minute, never-shut-off-the-camera videos.

Jo Reed: Oh, I think that would be fascinating.

<laughter>

Kelly Church: Yeah, and then-- I think it’s fascinating too-- and then we also have been doing-- taking pictures. I make little flashcards. But one of the most important things I do today is teaching youth. By bringing youth out into the woods and showing them now, in my mind it will be like riding a bicycle. You know, 20 years from now, 30 years from now, when those seeds can be replanted and the trees are old enough to harvest again, then these will be the kids that will be adults teaching the next generation and bringing back the harvesting part should we actually lose a generation or two.

Jo Reed: So you’re gathering seeds, you’re saving seeds, but when will it be even safe to plant these seeds?

Kelly Church: That’s a great question, and I actually asked that of Deb McCullough. She is one of the researchers from MSU University who discovered the bug, and so I’ve met her, oh, goll, almost 15 years ago now, and I asked her that early on, about 2006, “When will we be able to replant these seeds?” At that time I really didn’t get the gravity of the situation, and she said, “Maybe in controlled areas, you know, a while after the emerald ash borer leaves.” So we’re looking at, you know, at this point in Michigan, we might be getting near what people would call the end, the end of our trees. So I like to think that maybe on islands we could start replanting our seeds. You know, places where you actually have to move the bug to get there, and the bug can fly a mile by itself, so if we could find a island maybe three miles out somewhere and start replanting there, that would be ideal.

Jo Reed: So not any time soon for replanting, and how long does it take for a tree to grow?

Kelly Church: Yeah, not any time soon. We would want to save those precious seeds right now, and the trees that we harvest are usually about 20 to 35 years old when we harvest them. So we are looking at replanting, you know, remembering where you replant. Trying to have somebody who can stick with it for a few decades, definitely.

Jo Reed: This is the long view--

Kelly Church: Yes.

Jo Reed: but you’re optimistic.

Kelly Church: I am. I totally believe in my heart that we will not lose it forever, that we will be able to sustain it and that we can continue to make black-ash memories; I just won’t let myself believe otherwise.

Jo Reed: Back to basket-making: How do you begin a basket? Do you sketch? Do you let the wood tell you what it wants to be? How does it work?

Kelly Church: All in my mind. So it’s funny, because sometimes my husband, he would go to work and he’d come home and say, “Well, I don’t see any baskets made,” and then I would tell him, “Well, today they were being made in my mind because I was thinking about them,” and, you know, he thinks that that’s just me saying, “Oh, I did nothing today,” but really I am thinking. <laughs> I am thinking about the next project, the next idea, and so my baskets I don’t sketch. I just have them all in my head, and I have a lot of ideas in my head. You know, like when people say, “Oh, is it hard to come up with ideas?” No. I have a few years of ideas still to execute yet. The baskets take time to do, so I’m always excited about when, “Oh, I cannot wait to start that one,” or, “I cannot wait to start this one.” I like to have my baskets to also include messages for people just to educate people. Education is very important to me with the emerald ash borer situation, so educating them about why the basket’s important to us, why the tree’s important to us, you know, why do we care about these trees so much? Why should we care about the seeds? And it’s not just we as native people, but we, as everyone, should care about the seeds, because it is a tree that belongs to all of us, and black ash trees in particular grow in the wetlands, and when that stand dies, the water table will rise. So there’s a lot of effects all the way around by losing our ash trees.

Jo Reed: You’re known for many baskets, but among them is your beautiful strawberry basket. Tell me about it.

Kelly Church: The strawberry basket is made with the black ash. It’s a vibrant red, and then on top of it I put flowers and little tiny strawberries. So it’s like a strawberry blossom. My cousin, John Pigeon, and my father, Bill Church, are my two mentors and my teachers of all of my black ash teaching. So without either one of them, I would not be where I am today, besides my grandfather, who really got me, you know, interested in inquiring about it. So I was eating breakfast with my cousin one day and he said, “You know, Kelly, I have this great idea, but I think you could execute it well,” and so he kind of sketched out what a strawberry patch looked like, and so he was thinking more about a strawberry patch on the ground, and so what I thought of was putting the strawberry patch on top of a basket, and so our strawberries are our heart berries. They’re really good for our health. We have strawberry ceremonies. It’s also a very important time for our young women as they go into womanhood. Strawberries are very important for that. Our strawberries also represent forgiveness and, you know, just healing. It’s a basket that has a lot of different representations. People like to buy them for weddings, and then when people pass away as well, our people will sometimes put a strawberry basket in the casket with the loved ones for their journey.

Jo Reed: Do you ever surprise yourself?

Kelly Church: <laughs> You know what? I would say my last hat I made, my last top hat, it was one where I liked. I was like, “Oh, I like it. It even turned out better than I thought it would,” so...

<laughter>

Kelly Church: So occasionally, yeah, and sometimes when you execute an idea and you do it the first time, you look at it, you’re like, “I know just what I’ll do next time,” and so everything is always growing and evolving, but I think <laughs> as artists, we’re always our biggest critic as well.

Jo Reed: I am not going to let you go without you telling me about birch bark biting.

Kelly Church: Oh, <laughs> yes.

Jo Reed: I’d never heard of it before. You’re one of the few people who do it. What is it?

Kelly Church: So birch bark biting is done with really thin layers of birch. If you pick the bark off of a paper birch tree, and that’s the really white, vibrant one, around the time when the strawberries grow, and so it’s, again, you know, the strawberry’s really important time. When the strawberries start growing, the bark will be ready to pick off the tree, so it’s not really like, “Oh, hey, it’s June 20th today. It’s Bark Day.” You’re really watching, you know, the seasons. So when the strawberries begin growing, we start looking for bark. I use summer bark for birch bark bitings, and so when you take the bark off the tree, it has about 15 to 20 layers. I know no one would think that but it does, and they’re thinner than a piece of paper. So I’ll cut little squares and then I peel apart all of these layers down to one layer. The thickest I can do it is two layers. If you do two layers, you can fold it in half and I can bite a butterfly or a dragonfly, but if I want to do something like a turtle or a flower, then I need to fold it maybe four times, which makes the one layer more ideal. So it’s all about folding. You have to imagine. When you make the snowflakes with scissors when you’re a child, it’s kind of the same thing, except you’re drawing with your teeth. So after I fold it, depending on which design I’m making, I put it into my mouth and I have two teeth that work very well for biting, so it’s always on the right side of my mouth and it’s my eye tooth and the tooth below it, and then you have to imagine that you’re drawing with your mind. So when I teach people to do a butterfly, that’s what I’m telling them. “You have to connect your mind with your teeth, so you have to just think about how you’re turning it, which way you’re biting it, and where you’re placing your bites,” and so if I do like a flower or a turtle, you fold it four times. I know where to bite, and when you open it up, you know, it’ll have the design on four different sides, and so that’s how these designs are made.

Jo Reed: How did you learn?

Kelly Church: I actually learned from Ron Paquin, he is an elder from back home. He taughtme how to do them and this was the best advice he gave: He said, “None of them can be wrong. If you bite something and it doesn’t look like what you wanted it to be they’re all snowflakes” so <laughs> it’s like how can you-- if you can’t go wrong then it’s really encouraging. And so when I teach people how to do birch bark bitings I tell them the same thing, “There are no wrong bitings.”

Jo Reed: Where do you use them? Do you use them on baskets? Do you use them separately? I know you carve and you do all kinds of artwork.

Kelly Church: I’ll frame them. In the old days they would have done birch bark bitings and sometimes you would find the design perhaps underneath beadwork or crewelwork.

Jo Reed: You’ve talked about teaching, weaving, the process of making baskets, and the importance of teaching it to younger people. How do they respond to it? Is there an interest?

Kelly Church: Oh, yeah. So people will hold like black ash camps or they’ll have camps and they’ll have me come in and teach the kids. It’s not every child that’s interested. You’ll have some children that find it very difficult and they’ll lose interest right away. You kind of have to be there one-on-one with them. Then there are other kids that I can just watch around a room, and I literally do. You know, nobody knows I’m doing this, but every time I teach I’m watching the kids that are starting it and then they’re taking apart and then they’re trying it again, or the kids who are very patient, or, you know, the children who just kind of pick it up, like I said, the ones with the blood memory, and so those are the youth that I’m watching to take care of the next generation, the ones who want to do it, the ones who naturally get it, the ones who mostly want to do it. Because it’s not something that’s forced on you. So even though I came from a large basket weaving family, no one was saying when I was growing up, you know, “You’re going to grow up and be a basket weaver. That is what we do.” I think it’s really important to let people come to their own place in their own time, and so with these children I’m going to encourage them all I can and I will be there for them when they want me to be.

Jo Reed: You once said that basket making isn’t just what you do but it’s who the Northeast people are. I’d like you to say more about that.

Kelly Church: Yeah. The native nations of the Northeast. So it would be the Nishnaabe. That’s all of us in the Great Lakes area. The Iroquois and the Haudenosaunee, which is the New York areas, and the Wabanaki, up in the Maine area, and it is something that’s just integral to our people, but I do believe it’s that blood memory that makes it so precious to us. You know, why do we love this tree so much? It’s the stories that we hear from our ancestors, it’s the stories we hear from our families. I fell in love with basket weaving from hearing the stories that my grandfather told about him and his mother harvesting trees, weaving baskets, and then he’d always say this funny part, “But, ohhh, when tourist season came.” That was his worst time because his mom would throw down a blanket. They would put all the baskets out and have to sell them to the tourists all day, so...

<laughter>

Jo Reed: Well, Kelly, you’ve been named a 2018 National Heritage Fellow. Can you tell me what this award means? Not just to you, but to the community at large, to black ash basket making.

Kelly Church: Yeah. It is an incredible honor. I have to say that first. I’m very humbled and honored by receiving this award, and I don’t think of it as receiving it for me. I think of it as receiving this for all of us who do ash. It’s important to all of us because this is the tree that our people have always used forever, but it’s also something that is becoming a diminishing resource, and so I think being able to represent black ash with this fellowship will bring it more to the limelight, and it’s a real honor to be able to work with all the people that I do that are interested in it.

Jo Reed: It’s an honor that’s richly deserved. Your work is not just beautiful, but it’s also important. So thank you for all the work that you’re doing.

Kelly Church: Thank you.

Jo Reed: You just heard my 2018 interview with National Heritage Fellow and black ash basketmaker Kelly Church. You can check out her work at WoodlandArts.com. You’ve been listening to Art Works produced at the National Endowment for the Arts., I'm Josephine Reed. Stay safe and thanks for listening.

###