The Art and Science of Libraries

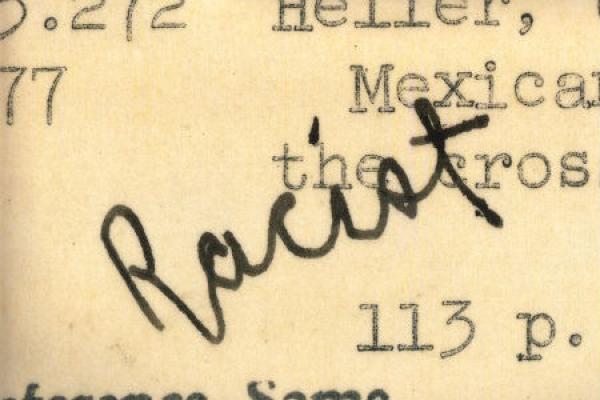

David Bunn, Youth U.S., 2004 (detail). Unique Iris print, Los Angeles Central Library catalogue file and plexiglass. Print 29 x 40 inches famed; Library card 5 x 7 x .25 inches framed. Overall dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and Angles Gallery, Los Angeles

In Youth U.S., Bunn magnifies the hand-written word "Racist" which was written on the catalogue card entry for the book Mexican-American Youth: Forgotten Youth at the Crossroads.

As someone who is completely enamored with libraries, I was immediately intrigued when I read about Library Science, a new exhibit at Artspace in New Haven, Connecticut. Open through January 28 and funded in part by the NEA, the exhibit explores our multifaceted relationships with libraries, as well as the many roles libraries have come to serve: they are places of order, stores of knowledge, community centers, and home to one of the most rapidly changing technologies of our time---the book. Featuring pieces from 17 different artists, the exhibit also includes four site-specific installations at libraries across New Haven. I spoke with curator Rachel Gugelberger about the exhibit and her own thoughts on reading and researching in the digital age. Dispersed throughout the interview are images from Library Science, with explanatory texts provided by Artspace about the larger works each image is from.

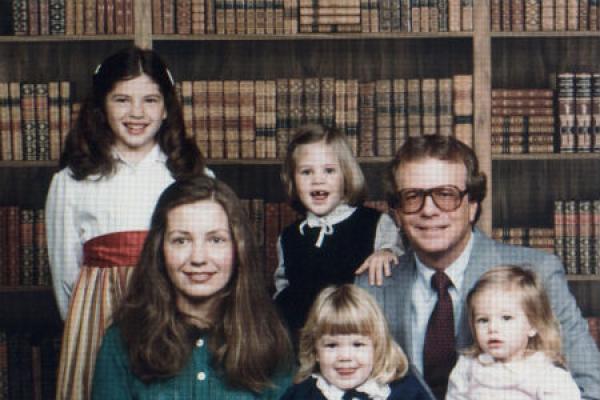

Mickey Smith, Corroborating Information, 2010 (detail). Five archival pigment prints in vintage frames. 4 framed photographs: 8 x 10 x 1 inches each. 1 framed photograph: 11 x 14 x 1 inches. Ed. 1/3. Courtesy of the artist and INVISIBLE-EXPORTS

In Corroborating Information, Mickey Smith has assembled and re-photographed found studio portraits that present the library---both fake and real---as the backdrop for portraits, exploring the relationship between the obsolescence of printed materials and the role of books in conveying status and mobility.

NEA: What inspired you to create the Library Science exhibit?

RACHEL GUGELBERGER: The earliest works I started seeing were focused on card catalogs. I have a particular attraction to them because my mother was a librarian. I remember when they were updating the card catalog at the University of California Riverside library, my mother would bring home the discards, and those would become notepaper for leaving messages or grocery lists, and what have you. So the first works I saw were a bit more nostalgic for me. And then Google announced what is now called Google Books, and the whole debate started about copying the world?s knowledge and making it accessible. I was of course thinking that [Google Books] was a digital parallel to many different variations of the universal library, whether it was the Library of Alexandria, or a fictional version in the case of Borges [and his Library of Babel]. And I realized that I wanted to do a project that looked at our relationship to the library.

Philippe Gronon, Catalogue des manuscrits, Bibliothèque Vaticane, Rome, 1995 (detail). Photographs mounted on aluminum panel. Five pieces at 28 x 40 inches each. Installation 28 x 197 inches. Edition 2/3. Courtesy of the artist and Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Philippe Gronon explores the idea of obsolescence vis-à-vis libraries and their artifacts in pristine black-and-white photographs that capture the surface details of the card catalogue at the Vatican Library, one of the oldest libraries in the world.

NEA: Have you seen your own relationship with the library change in the digital age?

GUGELBERGER: I feel that physically, it's changed things a lot. Perhaps there's a little bit less serendipity that happens when you're engaging with digital material, although there?s a whole different level that occurs when you?re online. But for me, it very much is about the physicality. I like holding a book. I get tired when I read online; I get uncomfortable when I'm sitting at the computer too much. I feel that the computer has kind of homogenized our whole life experience in some way. I appreciate that it makes things more efficient, that of course you can carry more books on a Kindle with you than you can if you carry a physical thing. [But] I feel that it's changed our relationship to information as well, and possibly in a way, we have less access, because I think we also have a certain kind of attention span that's developed as a result of our excessive computer use. If we don't find it on the web, we tend to think it doesn't exist, rather than being encouraged to go look for it in some other physical archive and really dig deeper.

NEA: Can you explain what you meant by saying that there's less serendipity now with the Internet?

GUGELBERGER: Well, there are quite a few projects in the show that focus on [how] when you?re browsing in the stacks, you see things that aren't necessarily meant to be next to each other because they've been misplaced. And because of someone's mistake or deliberate intervention with the library...you might stumble on something that might pique your interest. That kind of serendipity I think happens less online. I think what happens online is that you're distracted more, you're pulled away from your subjects. The distraction's just a click away. On the other hand, it might turn you into a much broader reader. But perhaps that's not the technology so much as the person.

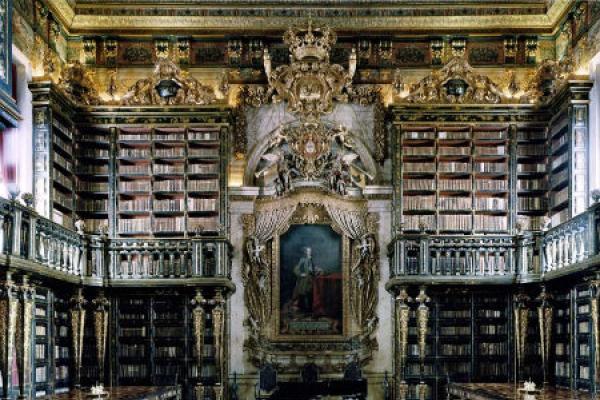

Candida Höfer, Biblioteca Geral da Universidade de Coimbra IV, 2006. C-print. 80.5 x 97.375 x 2.375 inches. Courtesy of Sonnabend Gallery, New York

The photographs of Candida Höfer capture the interiors of public and institutional spaces such as museums, zoos, archives and libraries devoid of human presence. Documenting the details of interior design, the intention of the space and the order and logic of the contents within, her images capture a universe of human knowledge.

NEA: How do view the role of libraries in the community?

GUGELBERGER: The public library in particular plays an incredibly important role, especially during times like in an economic recession. They're providing free materials, they are providing resources, sometimes there are workshops for resume building, free access to computers, to the internet, etc. So in that sense I feel like it's very important. I also think that in terms of larger communities, that [the library] is a shared space. When you?re working on the computer at home, or remotely, in Starbucks or what have you...the community is a little bit more dispersed. You don?t have to go the physical library anymore; you can go anywhere. To go back to what I was saying earlier about the recession is that at this time when more people in fact are needing the library and can utilize the library as a resource, library budgets are being cut as well. It?s an unfortunate situation.

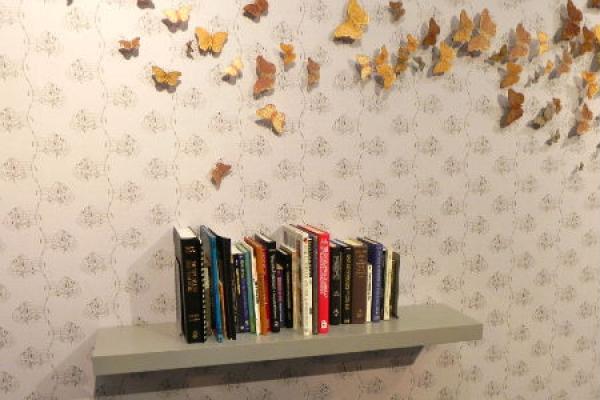

Melissa Dubbin and Aaron S. Davidson, CIA Reading Room for Kids, 2006/2011 (detail). All of the books from the CIA's Intelligence Book List for K-5th and 6-12th graders, wood and paper butterflies, glue, wallpaper, carpet, furniture, shelf. Installation dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artists

CIA Reading Room for Kids is a physical manifestation of the CIA's recommended reading list for grades K-5 and 6-12 as posted on their website. The wallpaper is based on illustrations from My Adventures as a Spy, a 1915 book by Lord Robert Baden-Powell, the founder of the Boy Scouts and a British spy. One of his disguises was that of a butterfly enthusiast. Prior to his service in South Africa, he spied around military forts, sketching the plans and armaments of each fort, and their size, type, and location of its guns concealed within the delicately drawn veins of the butterfly's wings and body. Veins on the ivy leaf show the location of a fort, as seen looking west (point of the leaf indicates north). The butterfly contains the outline of a fortress, and marks on the lines of the wings note the caliber and position of guns.

NEA: Is there anything else you?d like to add?

GUGELBERGER: I'm really not taking a stance. I feel that the library is adapting, and that's what happens with technology---technology has always informed the shape of the book. If we look back at the book, and how information was disseminated, first we had clay tablets, and then when we had scribes, we had scrolls, and then when we had the printing press, we started printing multiple copies. So in a way, the book and the classification tools used to archive it and make it accessible have always adapted to technology. I see the exhibition as having one foot in the physical past and one foot in the digital future.

Xiaoze Xie, Untitled #3, 2010. Oil on canvas. 20 x 30 inches. Courtesy of Chambers Fine Art

Xiaoze Xie contemplates the relationship between history, media, and time in photo-based paintings that reflect on the conditions of materials in libraries and historical events. Untitled #3 is painted after stills from the documentary Degenerate Art (1993), and presents a detail from a scene on book burning under the Nazi regime during the 1930s.