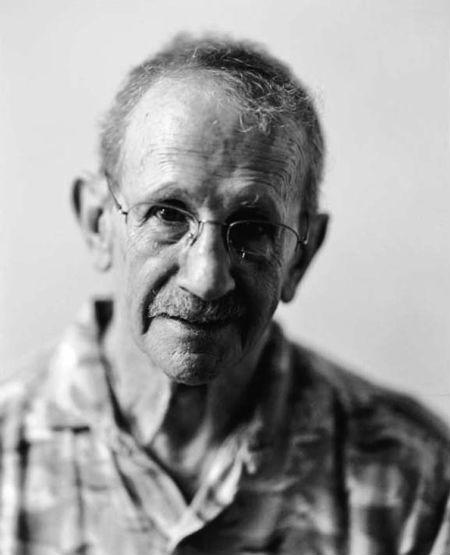

Catching Up with U.S. Poet Laureate Philip Levine

Photo by Geoffrey Berliner

Stretching from the car factories of Detroit to the Poet Laureate's office in Washington, DC, the arc of Philip Levine's life reads like a good story. Or in his case, like a great poem. Born in Detroit in 1928, Levine spent his early years mired in the industrial plants of auto giants such as Chrysler and Chevrolet. He eventually left the city’s assembly lines for academia, receiving his bachelors from Wayne State University and his MFA from the famed Iowa Writers' Workshop. In the intervening decades, he has become one of the nation’s most revered literary personalities, accruing three NEA fellowships, a National Book Award, two Guggenheim Fellowships, and a Pulitzer Prize before finally receiving the country’s top honor for poetry at the age of 83: the title of U.S. Poet Laureate.

And yet Levine has never left his roots far behind. The people and places of his Detroit days figure prominently in his work, and he has frequently been called “the poet of the industrial heartland.” With poignancy, painful realism, and sometimes scathing indictment, Levine exposes the humanity of working-class America.

We recently caught up with Levine at his office in the Library of Congress to talk about jazz, the power of language, and how the right person can make any place interesting.

NEA: Let's start by going back to the beginning. A lot of your work deals with your youth and childhood in Detroit, and your early jobs there. But you've been in the academic, literary world for many decades now.

PHILIP LEVINE: Since I was 30. So it's 50 years. I retired from teaching when I turned 80.

NEA: I'm wondering how you stay connected to those emotions and characters and imagery of your early years in Detroit.

LEVINE: Somehow those years seem more poignant, and they're carved in my memory much more deeply than my years in academia. I never felt like a secure fit in academia. In the late '70s, early '80s, I taught for a semester at University of California at Berkeley. And it seemed to me I was very successful. My students seemed pleased. And when they discovered I didn't have a doctorate, they were unable to keep me, because that was the rule. I wasn't shocked by that. I thought, "Oh yeah, sure. That's the same crap I've been living with." Except for the students, the semesters seemed to blend together. I had some remarkable students, especially at Fresno State. So that's what stands out.

But the jobs I had in Detroit, those were more difficult years. They were more angry years; they were more threatening years to my security. My wife and I and our kids lived in Spain two years, and they too seem very securely carved into my memory. Like all of us who write poetry, we really get our material from our memories. You look at some poets, and childhood is their main subject. It's not my main subject, although it's there and I do write about it. But that young manhood, which was so full of uncertainty and a kind of mental and emotional wandering—it's still very vivid. I don't really go to it; it comes to me. I'll be musing, and bingo, that's where I am.

NEA: What was the turning point for you when you found poetry in what you've described as “stupid” jobs, or in the anger, the feelings of threat?

LEVINE: Oh, I'd already found poetry. I was serious about poetry I would say from about the age of 19, 20, 21—somewhere in there. I got more serious, of course, as I got older. I still didn't know that it was going to be the major occupation of my life. There really wasn’t a turning point. If I go back in my memory and say, "Where did everything change?" it didn't change in any dramatic way. It changed sort of day by day, or year by year. I suppose the biggest change came when I met and married my second wife, because it brought much greater stability to my life. And then having children. In some ways it upsets your schedule, deranges you because you don't get enough sleep in the beginning. But on the other hand, it makes certain decisions for you. You can no longer join the French Foreign Legion. You can no longer just go chasing girls and drinking and being a total jerk. You have to settle down if you're going to be a responsible human being and do what's necessary. So my poetry was much more formal when I was younger. Usually we think of the young poet being a sort of Ginsbergian character and writing poems that are all over the place. But my life was so chaotic in a way that I had to find something stable, and I found it in my writing. But later, when my life became more stable, I could allow myself more freedom in my writing.

NEA: Since you write about people and places very frequently, do you think that you could write about anything and make it interesting? Is it a matter of perspective? Or are some places or people or experiences simply more interesting than others?

LEVINE: They're all interesting. Every place is someplace, you could say. But you could take me to a neighborhood here in Washington and it would look like something I knew out of Brooklyn or Fresno or Detroit. You take somebody else there, and it's full of memories; it's full of little totems he or she looks at and says, “I went there when I was 19 years old," or, "I went to someplace like that. That's where my mother broke down and cried. That's where this happened." So I think it would be very difficult to say there is no place worthy of poetry or no place that can sponsor poetry, for the right person.

And there's no place that can't fall upon deaf ears for the wrong person. You could take me to Paris and I'd say, “They charge too much for dinner here. Let's go." As many times as I've been in Paris, I've never written about Paris. It isn't for lack of trying.

Listen to Levine discuss his attempt to write about Les Halles in Paris

NEA: Do you have any poems that you have put in books that you've come back to and regretted, and wish you could un-publish?

LEVINE: Oh yeah. I'm not going to name them. There are plenty of people who are willing to name them, so I don't have to name them. I had to go back recently and look at some earlier books, because a woman who I like a great deal was starting a publishing venture and she wanted a book of mine that my publisher, Knopf, didn't own. So I went back to this one book, and it was painful. It was painful! I mean, there were some really good poems in it, but there were some really bad poems too. Sort of stilted. If I had it to do over, I would certainly leave them out. My first book got rejected many times, and now that I look back on it, I'm probably fortunate, because I kept changing it, dropping the poems I thought were the weakest. It would be hard for me to believe that there's any American poet over 65 who wouldn't look back at some of his earlier work and regret it. I shouldn't say regret it. I don't regret writing these poems because oftentimes they led me to really good poems. And sometimes both good and mediocre and bad, all three, can come out of a same sort of nexus of experiences and emotions.

Listen to Levine describe a time when he realized a poem stunk.

NEA: You've been described as a proletariat poet, a humanitarian poet. You've described yourself as giving voice to the voiceless. Given that, do you think that poetry can effectuate social change?

LEVINE: I don’t think so, no. I don't agree with [W.H.] Auden that poetry makes nothing happen, because it's had such a huge influence on me and many people that I know. But it changes us one by one. If it's aimed at that kind of universal change, it usually turns out to be crap. It's propaganda, and most Americans can see through that.

NEA: In an interview, you said that when you were younger, you believed that language could do anything. Is that still the case?

LEVINE: No, I don't think so. When I was younger, I didn't know as much. [Language] can do a lot. I mean, it's what we have. I would never complain about it, because I'm lucky enough to have grown up as a speaker and reader of English, which is a hell of a lot better than being, say, a reader and speaker of Walloon or something, with a reading public of 18. If you're gifted with English or Spanish or French, you have a huge reading public. And I think English is a particularly rich language. [It’s] maybe not capable of as much sonority and beauty, say, as Italian or Spanish, but its vocabulary is immense, and the combination of the Anglo-Saxon words and the Latinate forms—there are such wonderful contrasts and such depth in our language. I think it's a great language. It can't do everything. You can't fix your broken leg with words. But it does enough. And when you add silence to it, it does almost everything. Sometimes you need silence. Sometimes you need language. I think as I've grown older, I've become much more enamored of silence because one thing, it's so rare. I appreciate it so much. Living in Brooklyn, I'm in a “quiet” neighborhood. And if they stop building things, it would be quiet. And in Fresno, I also live in a very quiet neighborhood, but there are airplanes going over all the time. But I can find silence within the noise too.

NEA: Can you talk about that a little bit?

LEVINE: Well, once you stop struggling against the noise, if it isn't breaking your eardrums, it just becomes bad background music. It's just noise. There's a lot of music that's even worse than the noise.

NEA: True. Speaking of music, you're a huge jazz fan, I understand.

LEVINE: Yes.

NEA: Do you feel like jazz has influenced your poetry in any way?

LEVINE: It's a hard question to answer. People tell me it has. Jazz influenced my life more than my poetry. I was in school with these jazz musicians, some who became famous: the greatest baritone saxophonist ever, Pepper Adams; Tommy Flanagan; Kenny Burrell. When he was just a kid, I knew Elvin Jones, who played with Coltrane. And a woman named Bess Bonnier, a pianist. These people were pretty much in the same bag I was in, my age, and they were ferociously committed to music. I was so full of admiration for them. I had no question these men and women were going to go on and become professional musicians. They were the first real artists I ever met who were about my own age and were a kind of model to me. I thought, "If Kenny can do it, if Tommy can do it, if Bess can do it, I can do it." So in that way, they had a huge influence.

Also of course, it was the open expression of jazz; it was the wonderful sense of syncopation. The fact they could start with nothing and make something—all of that free-wheeling that goes on with jazz.

Listen to Levine talk about how jazz is bigger than sheet music.

NEA: Do you play?

LEVINE: No. No, I would have been so bad that I would have been shamed.

NEA: Do you ever listen to music while you write, jazz or otherwise?

LEVINE: Yes. When my kids were still home, I had to find a way of not hearing them, and I started with Indian music, ragas and stuff like that, and I would hear them so often that I wouldn't hear them anymore. So I could turn them up, and if they were killing each other—three boys—I could mask the things that I shouldn’t have been hearing so that I would have been a good daddy. That was the main function. I don't need it now, but sometimes I just play it anyway—stuff that I know really well. I have a record called [Cry of My People]. It's Archie Shepp, played sort of like gospel music just with a piano. He's on the tenor sax; he plays different saxophones, actually, on this record. It's beautiful. I don't much like him usually, his music—Archie Shepp—but he's got three wonderful, wonderful records. They're sort of free jazz, which honk and scream and purr. These are melodic.

NEA: Do you have an ideal writing environment in terms of where you are, or a type of day, or noise levels?

LEVINE: Time of day would be morning, about seven in the morning, in my study in Fresno. That's my ideal place.

NEA: There’s always the ongoing debate for writers about whether you need an MFA, or whether real-life experience is more important. You've had both. Do you think one is more important than the other?

LEVINE: No, I don't think so. I think it depends on the person. It isn't the degree that matters; the valuable thing is who you meet. Who are your colleagues—fledgling, rising, learning poets. And maybe you get a great teacher. I was lucky I had a great teacher, John Berryman. And I was lucky because I had terrific classmates. But I can imagine a situation where the teacher isn't particularly good, or isn't committed, or doesn't give a damn whether you learn, and I've visited enough programs to see it happen. My last class before I retired was absolutely stupendous. The students were so gracious to each other and to me. There was such generosity. There was a wonderful spirit. It was at NYU. I would think that any young poet, or young in experience as the age wouldn't matter that much—a learning poet—would have benefited from that class. If he or she didn't get anything from me, they would have gotten a lot from their classmates. So I think it's very valuable. It can save you an enormous amount of time.

I was so conscious of that when I took the class with Berryman. Or even the semester before when I was in [Robert] Lowell's class. I came into Lowell's class with a very inflated notion of how good I was. Well, I didn't leave with that notion. I was not a kid. I was like 26. But I had been in Detroit, and I was as good as anybody, maybe better. But I went [to Iowa] and I saw, "Those three people are ahead of me. I'm not saying they're more talented or they got more to write, but they're ahead of me." And I knew it. I knew it within a few weeks. And I listened to what they said, I looked at their writing, I talked to them, found out more about how they got to be who they were. Donald Justice was one, a woman named Jane Cooper. Those two were wonderful and generous, and I got a lot from them.

NEA: Okay, last question or two. How has it been being the Poet Laureate so far?

LEVINE: It's been a kick, you know? It doesn't change anything, and it shouldn't. It's fun. It doesn't say anything about who I am or what I've written or anything like that. I'm getting a lot more attention, which can be disastrous, I suppose, but I'm old enough so that it doesn't turn my head. My books are selling like mad. My editors and my publishers are thrilled with it. I met a lot of people I wouldn't have met otherwise. That's probably the biggest bonus, meeting people that I wouldn't have met. Like here [in Washington], I read for the AFL-CIO. That was really wonderful. I was invited to a writing group in Harlem. [It was] this writing group of 14, they were all sixth-graders, and they were fabulous kids. Their teachers were there. One of the kid’s grandmother's was there. A priest from the local church was there. A poet from the neighborhood, a guy who'd published. Some of them were white, some were black, some were Asian, some were Hispanic. But these kids were just off the charts. And it was all the work of their parents and these dedicated teachers. It was absolutely inspiring. I was there for almost two hours, just answering their questions. I never read a poem. They never asked me. They had already read me. They asked me questions about the poems. It was terrific.

NEA: If you could use your pulpit from the Library of Congress to change a misperception about poetry, or tell people something about poetry that we might not know, what would it be?

LEVINE: It's better than you think. It's richer than you think; it's much more about you than you would have ever thought. It's waiting for you, and if you don't go get it, you're the loser, because it'll be there forever.

Listen to Levine talk about the inspiration behind one of his favorite poems, "They Feed They Lion."

Special thanks to Adam Kampe for his help with audio recording and editing.