Community Theater? Not Exactly.

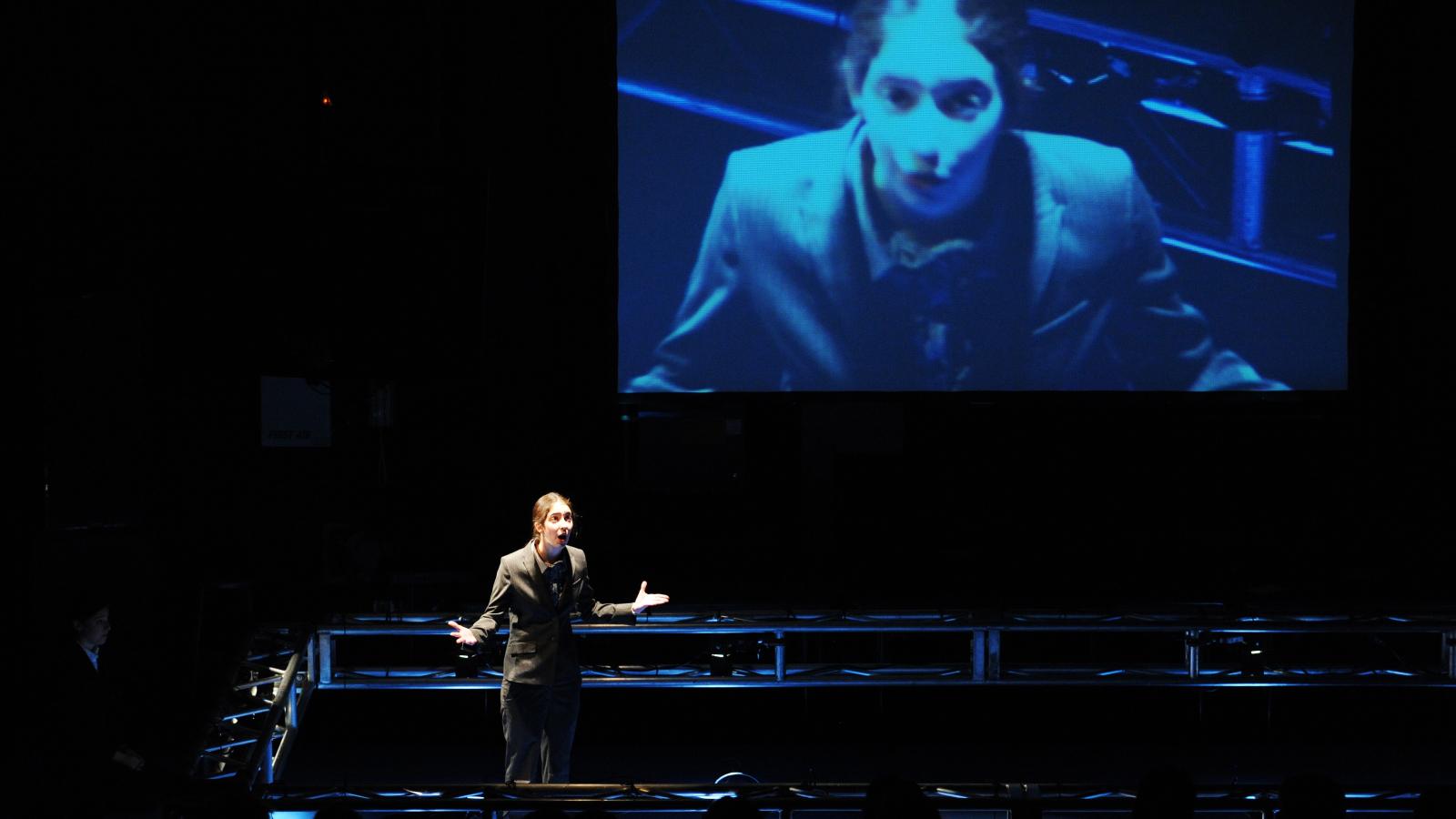

Sojourn Theatre's The Race at Georgetown University's Gonda Theater, 2008. Photo courtesy of Sojourn Theatre

There’s community theater, and then there’s Michael Rohd’s version of community theater. As head of the ensemble-based Sojourn Theatre, founded in 1999 in Portland, Oregon, Rohd isn’t satisfied with traditional notions of community actors or post-show talkbacks. Instead, his productions rely on active audience participation, and aim to encourage civic dialogue amongst both spectators and actors. Part drama, part social experiment, and part champions of social change, Sojourn’s shows have consistently pushed the limits of what theater can do.

Take the show On the Table, supported in part by the NEA. First produced in 2010, the show’s first act was staged simultaneously in two locations: Portland and the more rural Mollala, Oregon, roughly 50 miles apart. During the second act, both audiences took school buses to the same parking lot overlooking a river, where they celebrated the play’s fictional wedding by meeting, greeting, and eating a meal together. “Instead of building metaphoric bridges that we often talk about in making art, we actually traveled!” said Rohd. “One hundred people per night, from a city and a town, come towards each other to talk about the values in place.”

One of the company’s current projects is How to End Poverty in 90 Minutes. During the show’s hour-and-a-half duration, the audience comes together to decide how they will fight poverty using a portion of that evening’s box office proceeds. “Literally, we take $1000 in cash, dump it on stage, and the show is how the audience wants to spend that money,” said Rohd. During the play’s Chicago premiere, the company gave away $12,000 to local organizations that combat poverty. For that particular project, Rohd said, “The practice of the art itself involves giving back to the community.”

But Rohd expects the show’s in-house conversations to be just as influential as its charitable efforts. “Our hope is that whatever you come in thinking or feeling, we're making a space that's safe enough that you can have that point of view, but you can encounter different ideas,” he said. “We hope that for the audience, just like for us, every time that particular piece is performed, we're reflecting on our own perspectives and values around poverty and our responsibility for other community members.”

Of course, this type of spirited dialogue necessitates different perspectives, which is not always a given. To ensure spectators bring a mixed-bag of attitudes, Sojourn employs what Rohd calls “audience design.” “We're not putting up posters and hoping we get theatergoers to come,” said Rohd. “We work for months and months and months on building relationships with partners who will help us identify and bring in constituents who would not be in a room together otherwise.”

For How to End Poverty, the company worked with entities such as social service organizations and business councils in attempt to attract people with different opinions on and experiences with poverty. “That is as much a part of our creative work as the writing of the text or the staging of the piece,” Rohd said. “You have to rehearse the audience design as much as you do any other element.”

As he shifts the paradigm of art for art’s sake into art for community’s sake, Rohd is committed to using his creativity for a higher purpose. “My responsibility is to make work, projects, and practices that put me responsibly and curiously in relation to the larger world,” he said. “What's really powerful is the notion of people coming together—not just to be together, but to be in dialogue with each other. A great play, contextualized well, can do that.”

Interested in the relationship between theater and community? Check out the Center for Performance and Civic Practice, founded by Rohd in 2011.