Spotlight on Alabama Dance Council #NEAFall14

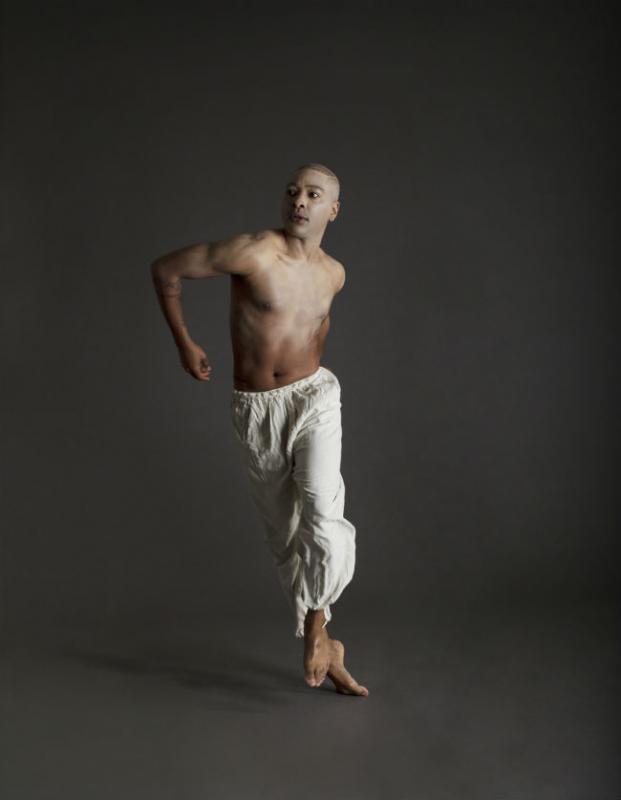

In 1965, it took three attempts for civil rights marchers to successfully and safely trek the 54-miles from Selma, Alabama, to the steps of the state capital in Montgomery. To honor the 50th anniversary of the marches, the Alabama Dance Festival—run by NEA grantee Alabama Dance Council—will be showcasing When the Wolves Came In, the latest work from choreographer Kyle Abraham and his company, Abraham.In.Motion. Divided into three works, When the Wolves Came In offers a powerful kinetic commentary on the meaning and history of civil rights, using the 20th anniversary of the abolition of apartheid and the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation as its frame. To further promote dialogue, the company will serve as the guest company-in-residence throughout the festival’s duration from January 9-15, 2015, engaging in performances and community events in Birmingham, Montgomery, and Selma. The NEA recently spoke with Kyle Abraham and Alabama Dance Council Executive Director Rosemary Johnson about the creative process behind the work, how it fits into current conversation about race, and why the world needs dance.

NEA: Kyle, could you talk about your creative process for When the Wolves Came In?

KYLE ABRAHAM: I think in a lot of ways, it started when I was down in Alabama the first time with Rosemary, just thinking about Birmingham, and about the work. After my trip to South Africa in 2012, I knew that I really wanted to dive into a work that was looking at the Emancipation Proclamation, apartheid in South Africa, civil rights, and where we might consider where we're at right now. So I was doing a lot of reading, and thinking about perspective on American and world history in different ways. Then I wanted to do a lot of diving into music. I love music in general, but [I was] trying to dive into music that was specifically written between ‘61 and ‘68. And then watching a lot of documentaries based on those different subject matters and getting into the studio with the dancers.

NEA: How did that research and that knowledge become translated into movement for you?

ABRAHAM: In some ways, it's the emotions that stay with me from my readings and my research that find their way into the work. But from that, I'm able to step outside of the kinetic world, look visually, and say, “How are we creating scenarios that aren't cliché but that address the subject matter?” So that's a big part of how the research is applied. And also, conversations. Generally speaking, the company and I work together generating, playing with things, making variations on themes, and then starting to put things in some kind of order. Ideally, it's not only me looking at different source material, but working collectively with the company. We then look back at the work and say, “Are we doing enough? Are we doing too much?” A lot of it is discussion. We talk a good deal in rehearsal, both in relation to the movement and to our research.

NEA: This work was in part inspired by jazz drummer Max Roach’s 1960 album We Insist! Max Roach’s ‘Freedom Now Suite.’ He made it very clear that he felt a responsibility to use his work as tool for social change. What’s your view on the relationship between artists and social change?

ABRAHAM: The two to me are inevitably intertwined. The sad thing is thinking about what this work’s inspiration is, and then seeing where we are right now and all the conversations that are coming up. Some of the works didn’t feel finished when we premiered them in New York. They weren't ready to say what I really needed them to say, and wanted them to say. To try and tap into something that is allowing it to have some kind of inclusivity, while addressing exclusivity, in a dance—it was difficult to do.

I've been talking a lot about artists whose work tends to veer more toward the experimental side of things, or the avant-garde. I think in some ways, saying that they don't want to address race or gender or equality comes from a place of a privilege. They don't feel like they need to. They can create movement and be present on a stage and it not be about their body or about their gender or about their skin color. But I don't think, to this day, that a black dancer or two black dancers in space, or a black dancer and a white dancer in space, regardless of their gender, can be onstage together and those issues not come up. That is really at the heart of thinking about politics and social justice and the performing arts, and art in general. As a black choreographer, regardless of my gender or sexual orientation, I think it's pretty much inevitable that the work is going to have some kind of politic to it, even if that's not my personal agenda. I have to be aware that what I'm doing has that capacity. I want to make sure that it's [using] that in a positive way that has some kind of hope to it, or raises conversation and questions that can lead us somewhere more positive.

NEA: As you mentioned Kyle, the past few months have seen increased debate and demonstrations focusing on race relations. How do both of you hope this work will contribute to the conversation?

JOHNSON: I have a personal connection to each city. I was born in Montgomery, I grew up in Birmingham, and then before I was in this position, I was fine arts director at a community college in Selma. So for me, it's a personal journey regarding life experiences, and living and dealing with a state that is very conservative, and finding constructive ways to talk about difficult issues in a non-confrontational way. Those are still things we struggle with. Hopefully some positive actions might come out of the residency activity that put us in a little bit of a different place, and allow us to talk about things that are hard to talk about in a face-to-face conversation.

Maritza Mosquera is director of outreach and community programs for Kyle's company, and she’s going to be moderating a community forum that will take place after each performance in each city. I think in terms of art for social change, we're hoping to have some concrete dialogue, [and for] teaching artists to give this a life of its own after the company leaves Alabama.

ABRAHAM: The exciting thing is thinking about what can be sparked. To be completely honest, I don't know if it's necessarily going to be the dance; I think it's actually going to be the fact that we're trying to engage so much. We're talking about not just what you see, but we're using the movement and the performance to be a partial catalyst for change. We're not thinking that the dance performance is going to change everyone's life, but we're coming at this with the knowledge that we need to make sure people feel as if we want to know more about them and want to hear their voices. It's through that trust and honesty that hopefully my entire company is going to come with. [We want to] figure out ways that the conversation doesn't become a cyclical thing. We address the cyclical nature of the history and the current state of events right now. We shouldn't be walking on a bridge for the same thing. We're walking more in unity, yes, but we're still fighting for the same things, just on a different bridge.

NEA: Rosemary, you brought up how art gives us a way to talk about difficult situations or issues that can seem almost impossible to talk about otherwise. What about art do you think breaks people's defenses down and allows us to have these conversations?

ABRAHAM: One of my favorite things about art is that you can touch people and no one has to know how it affected you, or the person sitting next to you. So I think there's a comfort in that. You can totally have your own personal experience. I think the next part of it is the conversation that happens as people discuss what they see and how they saw it.

JOHNSON: It's a way to remove yourself, to step outside of yourself, and talk about what you see and what it meant to you without having to confront someone about it. What I'm most interested in seeing is how Kyle's work affects people in different ways, because I know it will. Each person is bringing their own life experiences, no matter what their age is, and somehow that movement is going to speak to them about their life. And so being able to talk about that afterwards is a safe way to maybe even bring up some of the things that bother you—things that happened to you, or things that you experienced—that were negative. But it would allow you to talk about it objectively without that particular event being the focus of the conversation. It's the art that's the focus of the conversation.

NEA: I know that working with schools is a major component of the festival. Why do you think arts education important?

JOHNSON: So many kids don't get the opportunities I had growing up in the schools and having access to the arts. But through the residency program, and giving teachers tools they can use and giving artists that work in schools special tools they can use—that's a way to bring the arts to our students in Alabama.

ABRAHAM: Dance for me didn't happen until really late in the game, like age 16, [when I saw] my first dance performance, and then decided to go to the performing arts high school half-days senior year. We had the Bill T. Jones dance company doing a lecture demonstration of Still/Here when I was 17. Hearing that company speak, and talk about who they were, made me feel prideful about who I could be. So separate from thinking about being a dancer necessarily, or being a choreographer, seeing these people move with such passion, and with such a great ownership of who they were— that was exciting to me. It made me feel like I should feel proud of who I am.

Moreover, art class was one of the only classes that actually blended kids from different academic skill sets in the same room. It made us all equal in a way that the academics in my regular high school did not. The highest academic level classes were all on the top floor, and the lowest were in the basement. Oddly enough, all the art classes were on that top floor, so everyone would be in those classes. It made me feel accepted. Allow[ing] people to blend together in a way created this whole other acceptance that I know I needed going to the high school that I went to. In the bloods territory, so there's that.

Separate from all that, there's a respect that then happens when people are able to see your work, and teachers are asking students to critique each other's work. Then people are giving honest feedback about what you do, and there's a level of respect that's going back and forth. Moreover, [the arts] make it much easier for someone like myself to tap into why the academics were important. It wasn't really until I started studying dance in the performing arts high school that I actually tried in school. It was the art classes that made a lot of the history and the literature that we were reading—it made it all relative. So it brought excitement to every other aspect of school, which of course then plays itself out in how people are then thinking about their future.

NEA: We need dance because...?

ABRAHAM: I don't want to sound cliché in saying that it changes lives, but it does. It's healing, it's affective. Dance to me is the boiling point of everyone's emotions. If you don't like it, you're frustrated, and you drive yourself crazy. If you love it, there's that chance that it's going to drive you over the edge with passion and emotion and of course. It's all rooted in passion in some way, because why else are we doing this? Why not just be doctors and make lots of money? [laughs]

JOHNSON: For me, I think movement is life, and so dance is a snapshot of life. To me, it's an all-encompassing art form. My training as an artist is in music, and I think the thing that fascinated me when I immersed myself in the dance world for the first time, was seeing the music come to life. It was like a 3-D version. It was just fascinating to me that I could actually see the art moving, instead of just listening. That was my entry point in terms of what dance means.