#ADA25: Disability Rights through Tom Olin's Lens

Before the Americans with Disabilities Act was passed 25 years ago, curb cuts were a rarity, making sidewalks inaccessible to people in wheelchairs. Nor were there guaranteed ramps allowing entry into buildings—including schools and courthouses—or wheelchair lifts on public transportation. Employers could deny employment if a person’s disability seemed onerous to accommodate, and families often institutionalized disabled relatives to avoid the dual burdens of shame and physical care. But in the 1970s and 1980s, the disability rights movement began to gain traction, empowering a group of people who, throughout history, have often been hidden within their own homes.

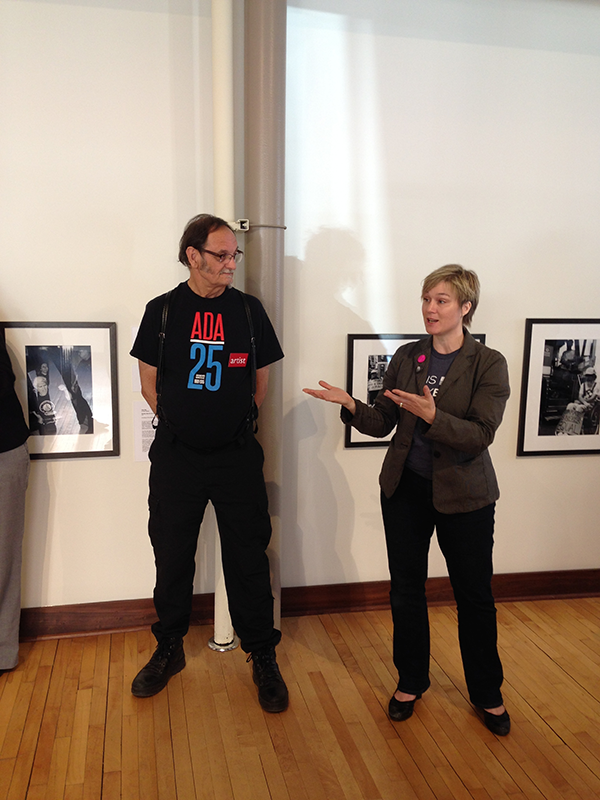

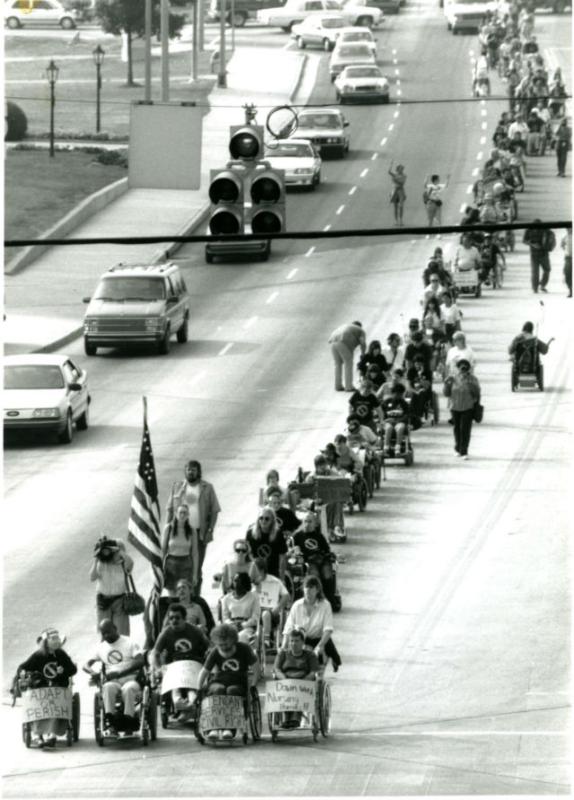

It also empowered photographer Tom Olin, who began to document civil actions and protests, turning his camera into a tool for social justice. He was there when activists blocked traffic as they rolled through downtown Atlanta, and he was there when activists—including his then eight-year-old niece Jennifer Keelan—left their wheelchairs to crawl up the Capitol steps to demand equal rights. Today, he is a critical figure in the disability rights movement, not just for his work as a social documentarian, but for his tireless advocacy spanning three decades.

We recently spoke with Olin from the ADA Legacy Tour bus, a traveling exhibition that he and others have driven across the country for the past year. The goal is to “raise awareness and build excitement” for the ADA’s anniversary on July 26th, when Olin will be back in DC not to protest, but to celebrate. Below is an edited version of our conversation.

NEA: How did you become interested in photography?

TOM OLIN: I think I was always interested in any kind of the media arts. It was a way even in high school to see and to feel. I never had a camera when I was young, but when I went to Berkeley at the end of my 20s, I decided to look into video production. I thought that was a way to communicate to more people. I ended up in a video production company, and one of the things that I did was I worked on a video camera. When I looked into it, a few times I thought I should get a little bit better composition. So I took a 35 mm class at a small community college. The instructor took a liking to me. His work was very well-documented around the Bay Area—he did a lot of the first hippie and free love photos. He told me to follow him around, and I learned through his eyes what it meant to take photos.

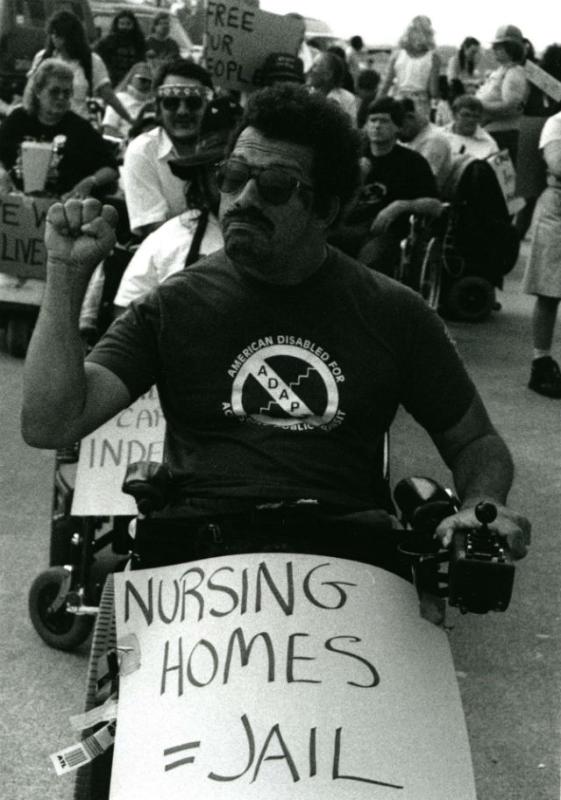

At the same time, I was working as an attendant with people [with disabilities] around the Bay Area. Those were the people that were my subjects. The first series I ever did was of a person that had chemical sensitivity. Trying to show that through 35 mm was not the easiest thing to do, but it was interesting. It became a little show there in Berkeley, and then from there I just kept on taking photos. I ended up within the year or so moving to L.A. where there was a group of people with disabilities that I was very much in touch with. We were very active in trying to get UCLA more accessible. Around that time, Wade Blank and Mike Auberger from [disability rights organization] ADAPT, which had just formed, were coming to L.A. in the fall of ‘85. They came down and we went to a national action. I took my camera but I only had one roll of film, and that wasn't even a roll of 32—I had a roll of 24. So my first action I took 24 pictures. I still use a few of those photos. One has become a very iconic photo of a hand handcuffed behind a wheelchair, and that was on that first roll of the first national action I had gone to. So that was my start as a social documentarian for the disability rights movement.

NEA: So did your interest in disability rights stem from your time as an attendant?

OLIN: I grew up with dyslexia, and I had to go to the “dummy class.” So I knew what it felt like to be on the outside, and have people look at you and think that you were less than what they were, just by having a disability. Having that, and then later on, working in a rehabilitation hospital when I was around 19 years old in Grand Rapids, Michigan, I got to look at disability in another light, and understand that there were other disabilities that people had prejudices against. It was very hard to take a person that I was working with out into the community when things were not even accessible. I remember taking someone to the movies. Finally we found a theater that you actually could get into and they had to sit way in the back. Thank God we had a van from the rehab facility, because how can you get from one place to another place? These sidewalks didn't have curb cuts! So I learned a lot from being an orderly at a rehabilitation hospital.

NEA: When you first started taking photographs of the people you had been working with, was it your intention that this would become a tool for social justice, or did that evolve over time?

OLIN: It actually evolved really quickly. When I moved to L.A., I became a teaching assistant in the L.A. Unified [School District] in the special ed programs. I ran into a lot of young people that had no idea about other people with disabilities. There wasn't even very much [material] for the teachers. I'd bring back photos that I had taken of people with disabilities, and later on, of different actions and demonstrations. I can remember once taking a book of photos into a mainstream classroom. I was a one-on-one assistant to a young person that had been mainstreamed—he was the only person in a wheelchair in the whole school. That person opened up the book and the first picture he saw was of a group of about 50 people [in wheelchairs] in a line marching down a street. He turned real quick and said, "I didn't know there were that many people in the whole world that were in chairs." Of course—he'd never seen them, and we didn't have the ADA. No one was out of the house. I had a headline [in the album] about an action out of San Francisco from TIME magazine about the group ADAPT, which I followed, and took pictures of at actions. TIME called them "wheelchair warriors." That kid saw that phrase and just smiled and said, "I can be a wheelchair warrior!" So you can see how I felt when I realized that people could be impacted by photos, especially young disabled people. One of my favorite new venues around that time was the Weekly Reader. I realized here I was able to show people images of people [with disabilities that were empowered and they were fighting for something. There hadn't been photos of people like that before.

NEA: How do you think your photographs have helped shape public opinion and public policy?

OLIN: There was a time when I worked with Lucy Gwin, who was the editor of [disability rights publication] Mouth Magazine. A member of the Clinton administration ordered eight copies of every issue. Back then, people needed to actually see photos. When something is so new, if you talk about it, you can't really see it in your mind until you see it visually sometimes. Seeing a photo of people that were like you was very different than reading about it. It's something I've seen over and over. I've even seen it internationally, where people in Brazil had heard about people in the United States [taking action]. But until they actually saw the [disability rights publications] Ragged Edge or the Mouth or Mainstream magazine with photos in it of people actually doing what they were talking about, they didn't feel like it was real. And when they did see it was real, they became active in those countries. It's just something that just happens. It's not that I think photos are more important than words, but they do something to you, they do something to your psyche. It's a roundabout thing that you can grab and hold onto. Words are sometimes more slippery. People know that people can lie with words, and back before Photoshop, photos couldn't lie.

NEA: Do you think your photos influenced the passage of the ADA?

OLIN: It influenced it on two different levels: policymakers saw that there were people out there in the country actually doing something. And for sure it was helping people on the ground, the grassroots, to look at photos like this and say, "Hey, it's happening just 100 miles from here. It's happening in the next state. Look at what this group is doing." They could say, "We are not the only ones." And that feeling kept on going throughout the ADA. If there was something happening, we would go right to DC and make sure that [policymakers] knew that we were out there. I can't remember how many times ADAPT went to DC and took over. There's an exhibit that the Department of Transportation is co-sponsoring right now [at the Smithsonian Museum of American History]. We had taken over the whole DoT building at one point in the ‘80s on fighting for the transportation section of the ADA. Now they embrace it as a part of civil rights.

NEA: What has it been like for you to watch this evolution of this movement from such an intimate perspective?

OLIN: I just spent some time in New York City with my [bus] driver. We got to take some photos out and show them to some students. They're just learning about the history, and for them to see not only the photos but to meet someone who has been there is very important, still. It's not over yet, by a long shot. We don't have everyone out of the institutions that want to be out. That’s something that the ADA has been trying to address. They're trying to get a community integration amendment into the ADA. So it's something that is alive. This is a civil rights law—it's alive and you have to keep it alive. That means taking it to the next generation and the generation following them. What the whole ADA, for me, stands for is getting people into the community. Until that last person that wants to be in a community is in that community, and we have economic justice for all in that community, then I feel we've got a long ways. We're getting there. I think we're on the right path.

NEA: Can you tell me more about what does the ADA mean to you?

OLIN: It means that I can take a friend and we can go to the movies, we can go to a gathering, and know that we can get there together, we can hang out and be entertained together, or be at a restaurant or a movie theater. Before there were curb cuts, a lot of times people were just stuck in their houses. It was just too hard for them to get anywhere. Now the kid that did not know that there were hundreds of thousands of people with disabilities and wheelchairs knows that he’s not alone. That's what the ADA means to me, that people with disabilities have a community—not only their own disability community, but they can be a part of any community in the U.S. And if it's not us, it's our parents. I think we're all a little scared of how disabled our parents are going to become. In the fight we're doing, is a fight not only for those who have disabilities because of being older, but also because of giving up their bodies for our country. Anyone can become disabled to fast. I have police officers who suddenly realize that the people that are on the other side of the line protesting are also the people helping them and their brothers who have been wounded in their line of duty. It's a movement that helps all.