#artistcrush: Syracuse edition

Right now the mention of Syracuse brings to mind all things basketball. Syracuse is currently the home of the 2015 NCAA Men's East Regional Finals after all. But for me, Syracuse will always bring to mind two artists who had a profound effect on my relationship to the arts in my formative years: screenwriter and media visionary Rod Serling--born in Syracuse--and visual artist and MacArthur Fellow Carrie Mae Weems who has a studio in Syracuse.

Remember 1991? That was the year Child's Play 3 was released in theaters. Barely 11, I couldn't see the movie. But the latest movie about "Chucky"--a killer doll with a bevy of one-liners--was discussed in whispered huddles amongst my classmates, much to the chagrin of our teachers. So when my mom asked me what we learned in school as I did my homework at the kitchen table, I instead shared my classmates’ talk about Chucky in class. My mom was amused. My uncle, who was in earshot, said "Oh, Chucky? That's not scary. I'll tell you what's scary: Talky Tina!"

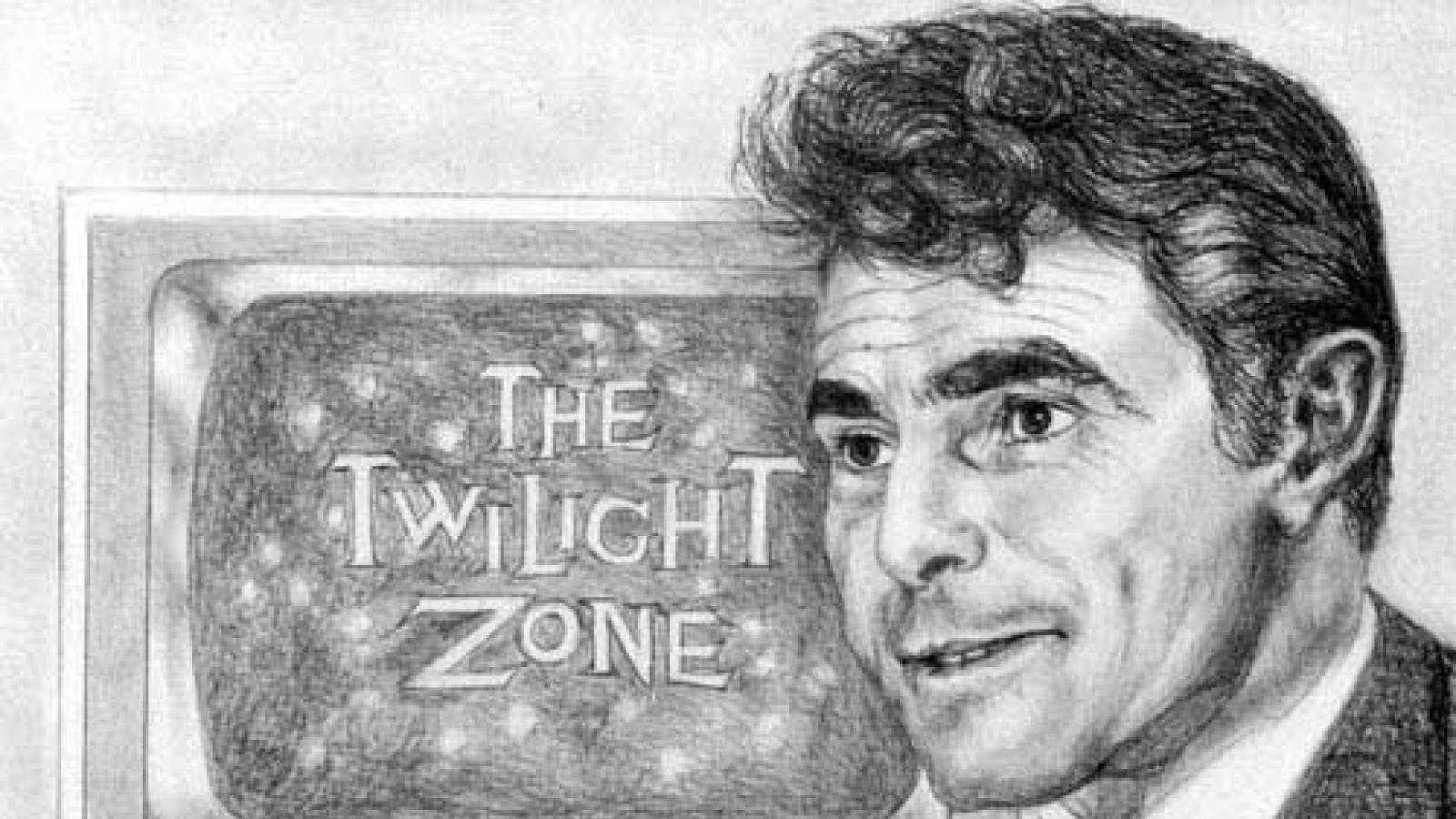

My uncle told me it was the scariest thing he'd ever seen on this show called The Twilight Zone when he was a kid. I told my uncle nothing could be that scary "back then.” Nothing in black and white TV, nothing before Chucky. Fortunately my uncle owned episodes of The Twilight Zone on VHS (remember those?) and soon as my homework was done, I was off to my very first viewing party. From the start of the eerie music and Rod Serling's otherworldly cadence and narration, I was hooked! And yes, totally scared of Talky Tina from the November 1, 1964, episode "The Living Doll."

I made several weekend trips to the library to check out the rest of the Twilight Zone series after I exhausted my uncle's collection. I became obsessed with knowing more about Rod Serling. Where was he from? What inspired him to create this amazing television series back then? What else did he create? It was in the library I discovered that Rod Serling was born in Syracuse but was raised in Binghamton, New York. As a child, I always took great interest in knowing where people were born, so I filed Syracuse away in my mind with fondness, along with the certainty it was much colder than my Louisiana home.

I also learned Serling was the creative force behind the original Planet of the Apes film and envisioned the film's now iconic twist ending. Through my research, I got to know more about Rod Serling the artist and how he used his artistic skills as a storyteller to show the world what strengthened our humanity, like compassion and intellectual curiosity, but also to make public those things that weakened our humanity, like racism and bigotry, earning him the moniker of "television's last angry man."

Little known fact: Rod Serling produced a script "Noon on Doomsday" inspired by the murder of Emmett Till. The television networks at the time deemed the script too controversial. Indeed for one of my favorite Twilight Zone episodes, "The Monsters Are Due Out on Maple Street," Serling's ending monologue resonated strongly with me as a black girl growing up in the deep South: “For the record, suspicion can kill, and prejudice can destroy. And a thoughtless, frightened search for a scapegoat has a fallout all its own, for the children and the children yet unborn. And the pity of it is that these things cannot be confined to the Twilight Zone."

I soon discovered Serling's Night Gallery series at the library. My apologies to the Met and Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler, but it was Night Gallery that instilled in me an intellectual curiosity for the mysteries of museums. Night Gallery was Serling's television series that followed The Twilight Zone, airing from 1969-1973. In each episode Serling unveiled a painting representing a macabre moment frozen in time to introduce the story. It was in Serling's Night Gallery that I learned that a painting's context, not just its content, was key to understanding how art works. I also spent time reading short stories in The Night Gallery Reader and getting an introduction to genre-defining giants like Ray Bradbury and Richard Matheson. It was around this same time I spent Saturday evenings with my dad watching Star Trek: The Original Series and started to see similar parallels to The Twilight Zone in Gene Roddenberry's groundbreaking series. Little did I know, I was what we now call "geeking out."

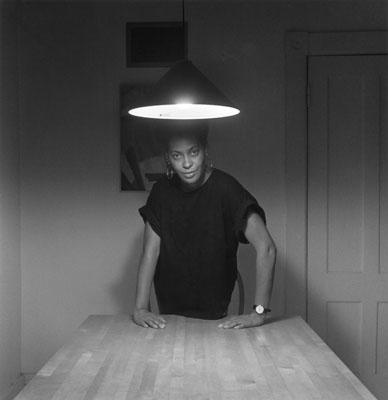

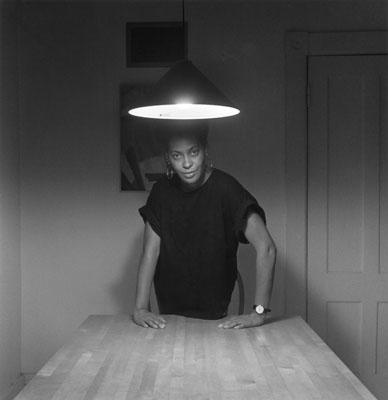

Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled (Woman standing) From the Kitchen Table Series, 1990, gelatin silver print, 28 1/4 x 28 1/4 inches. © Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Fast forward to my freshman year of college where I was intent on becoming a psychology major. Nothing was going to stand in my way until I learned I needed a certain number of art credits. Enter, art history. It was in Professor Joan DelPlato's survey of western art that I was introduced to the art of Carrie Mae Weems through The Kitchen Table Series. The series read as a narrative tableaux collectively, yet individually each picture had a story to tell. The tension in the framing of Weems and others in the photographs around a kitchen table gave a clever caution to the viewer as if to say, "nothing in life is truly ever black and white" even in the most common places. I was enamored by Weems's ability to capture the rawness of relationships coupled with the complexities of race and identity in her photographs. As I studied more about Carrie Mae Weems's work, I learned about her background in folklore, and how her art subverts and challenges notions the black female imagery.

Each scene in the "Kitchen Table Series" was a glimpse into a larger story still unfolding for me. Not only was I a part of that story, but I could have a role in telling that story. Maybe I could be more than just the conscious collector of art. Maybe I could be a curator or a museum educator in a position to support museums as environments where visitors as learners can have a space to engage authentically on issues like race and identity in the work of Weems and other fearless artists. It was the first time I considered having a career in the arts as I saw how much the arts mattered for me and society.

My senior year I decided to focus my honors thesis on representations of the black female self, examining the art of Carrie Mae Weems, along with Adrian Piper and Emma Amos. While most of my fellow art history undergrads were researching artists who had long passed I remember the excitement in my voice when I told my professor there was something invigorating about writing about artists who I could one day meet. She replied, "Well you know Carrie Mae Weems teaches in Syracuse and has a studio in NYC?" It was as if the earth stopped. Did she just say Syracuse? I smiled and suddenly wished more than anything I could fill the room with the Twilight Zone theme song. In that moment, I put together the pieces that somehow, across time and space, Rod Serling and Carrie Mae Weems both nurtured my geeky tendencies to another dimension--one of artistic stewardship, a process that could only be found in The Twilight Zone by way of my kitchen table, the local library, and, of course, Syracuse!

#artistcrush is an occasional series in which we ask NEA staffers and other friends to write about artists and other cultural figures they admire. You can check out the series kick-off by Adam Kampe on Sufjan Stevens here.