A Helping of Holiday Art History

Ah, December. A time for family, friends, and frosting binges. But it’s also a time for art. Snuck in there between the gifts and the Hanukkah gelt are poems, folk songs, and symbolic pieces of visual art. In fact, they’re so ingrained in our festivities that most of us think of them simply as traditions rather than pieces of artwork. Here’s the skinny behind a few notable pieces.

“Auld Lang Syne”

New Year’s wouldn’t be New Year’s without champagne and “Auld Lang Syne.” Granted, most of us are only vaguely certain about what the lyrics actually mean, but with good reason: it’s written in an old Scottish dialect. As it turns out, the tune is an old Scottish folk song, which was passed down orally until Scottish poet Robert Burns set a reworked version to paper in 1788. A few years later, it was published in an anthology of traditional Scottish songs called The Scottish Musical Museum, which standardized the song for the future. In case you’re wondering, “Auld Lang Syne” is actually a song of reunion, not of parting, and it has been used at conciliatory events as varied as the Christmas Truce in World War I, when British and German troops sang it together, and at the end of the Civil War, when General Grant ordered a military band to play it as a symbol of the country’s reunification. So how did it become a New Year’s Eve staple? That’s due in large part to Guy Lombardo and his Royal Canadian Big Band, who played it on New Year’s Eve radio and television shows beginning in 1929.

White House Menorah

Since 1993, every sitting U.S. President has presided over a menorah-lighting ceremony at the White House in celebration of Hanukkah. This year, President Obama turned to the public for help in choosing which menorahs to light by asking, “What’s the story behind your menorah?” Of the two selected, one came with a particularly poignant story about how art and beauty can persist in the darkest of dark times.

Erwin Thieberger began making menorahs while interned at the Auschwitz concentration camp during World War II. Trained as a mechanic, he made these early works from scrap nails and solder—whatever materials he could find. After emigrating to Maryland, making menorahs became a favorite hobby of Thieberger’s, and he fashioned hundreds by hand before his death in 1987. He continued to make most from solder and concrete nails, recalling his earliest materials in Auschwitz.

On the fourth night of Hanukkah, one of Thieberger’s menorahs, made of nails, was lit at the White House by fellow Holocaust survivor Manfred Lindenbaum. However, it wasn’t the first time Thieberger’s has been featured on federal grounds: in 1980, he donated a menorah to President Jimmy Carter (it now lives at the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library in Georgia), and another of his menorahs was lit for many years during Hanukkah celebrations at the U.S. Capitol building. His work, including chandeliers, was also featured several times at the Smithsonian’s Festival of American Folklife.

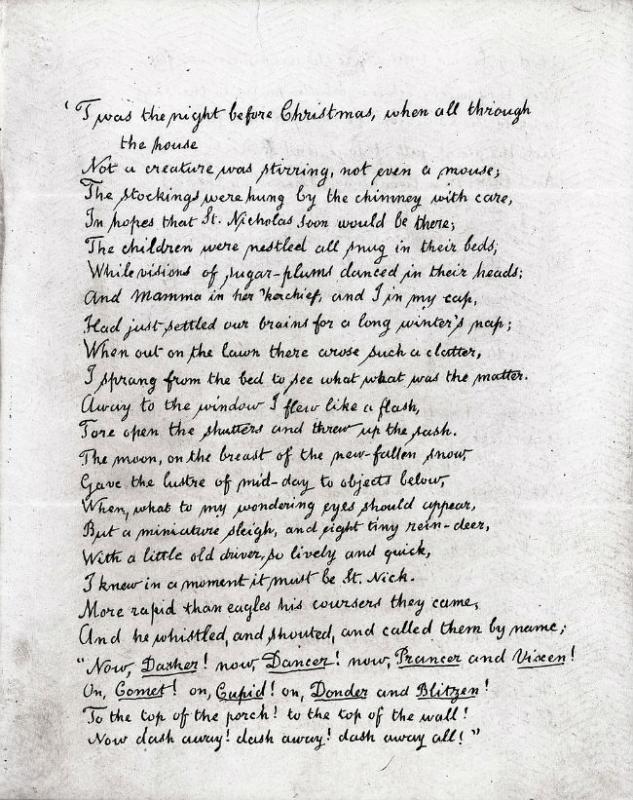

“A Visit from St. Nicholas”

One of the best-known poems in American culture, “A Visit from St. Nicholas” (frequently referred to as “’Twas the Night Before Christmas”) was first published anonymously in 1823 in the upstate New York newspaper the Troy Sentinel. It had been penned the year before by professor Clement Clark Moore for his children, and was submitted to the paper by a friend of Moore’s. As a distinguished scholar, Moore distanced himself from the children’s poem. However, at the urging of his children, he definitively responded to speculation that he was the author when he published the verse in an anthology of his poetry in 1844.

As the poem grew in popularity, it helped solidify a number of concepts that are now firmly rooted in American Christmas tradition. For example, the number and names of Santa’s reindeer, and the fact that he makes his house calls on Christmas Eve rather than Christmas Day, or some other date during the Noel season.