Taking Note: Can/Should We Distinguish Between Basic & Applied Art?

I'm writing this from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, just off Dupont Circle in Washington, DC. Although the focus of the workshop I'm attending is not explicitly (or even largely) on global welfare, the dialogue here, if it precipitates action, could have striking implications for how postsecondary schools do their part toward this larger goal.

With support from the Mellon Foundation, the workshop is being convened by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Its aim is to help the sponsors determine whether a two-year study is warranted to explore "integrating education in the arts and humanities with education in science, engineering, technology, and medicine."

The meeting so far has included brief speeches by National Endowment for the Humanities Chairman William Adams, Susan Albertine, a VP at the Association of American Colleges and Universities (AAC&U), Laurie Baefsky, executive director for the Alliance for the Arts in Research Universities (A2RU)—which receives funding from Mellon—and, among others, Norman Bradburn, a senior fellow at NORC at the University of Chicago (and himself no stranger to NEA research).

In addition, researchers from Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania, presented a tentative theoretical frame within which to consider opportunities and obstacles for integrating the arts and humanities with STEM in higher education. Their findings were grounded in a review of the relevant landscape and literature, and in their own experiences as educators in the social sciences and in engineering.

A closing session on the agenda promises to discuss "is there sufficient 'preliminary evidence' of the benefits and the process of implementing such experiences on our campuses" as well as "what is our definition of 'evidence'? What kind of data do we need to create a solid evidence base? What is the value of 'narrative' and 'testimonial' in assembling the evidence base?"

As research director at the NEA, I naturally gravitate toward these questions. Still, I want to pose what might be considered a “meta” question about such collaborations and then attempt to answer it.

*

Many examples exist (some were shared at the workshop) of scientific and technological endeavors that have benefited from artistic practice or pedagogy. “Design thinking” leaps to mind, but so do arts integration with medical training, or artists who help scientists visualize their data, especially to communicate a public health message. Indeed, scientists at the workshop—and at similar events I’ve attended in the past year—readily acknowledge that the infusion of the arts and humanities could awaken in scientists and engineers a capacity for emotional connections, creativity, and complex problem-solving that might lie dormant without such exposure.

My question: if we strive for full integration, then what new “habits of mind” (as one workshop participant called it today) should be cultivated by STEM-related training for arts/humanities students? Or is the relationship not in fact bi-directional?

Artists perennially have raided scientific topics and themes as subjects for their creations, but how often have we seen scientifically validated techniques or hypothesis-building brought to bear on the artistic process? Arts funders and arts organizations, to be sure, have leveraged the social sciences to good effect, as I seem never to tire of pointing out—but less visible are instances of artists or arts organizations embracing the scientific method (or indeed science literacy) as a factor in their productions. Nor is it necessary or at all desirable that they should.

This conclusion, if tenable, implies that while STEM-related knowledge should be valued as an integral part of the formal education system for everyone, it may not follow that—just as artistic techniques and mindsets supposedly enhance STEM education—scientific approaches hold a reciprocal value for artists or arts organizations. Nevertheless, there is at least one trope from the scientific methodological literature that could be worth weighing in an arts context.

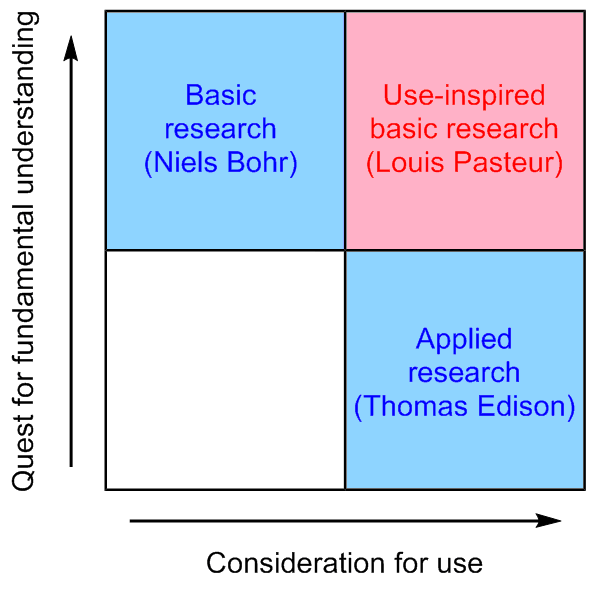

The distinction between “basic” and “applied” research just might be useful when we consider how so many arts projects these days are intentional in serving a broader social agenda. Think of creative placemaking or the use of arts practice and therapy in healthcare settings. Think also of the arts’ inclusion in programs about social justice and equity, or in rehabilitation strategies for prison populations.

It’s clear to anyone but an outright philistine that the arts matter not only for these tangible contributions to individual and societal health and well-being—but also for outcomes that may not have been intended. Just as basic scientists (typically “bench” scientists) keep working at problems that have no immediate consequences for human well-being or productivity, so too should researchers (and certainly evaluators) recognize that many (most?) artists do not seek deliberately to solve an individual or societal problem. By freeing ourselves up to consider artistic practice along this continuum—and it is a continuum, as “basic” can be the scaffolding for “applied”—we avoid holding all arts projects to the same sets of outcomes. We also retain an appreciation for “non-applied” practice as equally legitimate.

This is all a bit of a thought experiment, but right away I spy one potential threat. Scientists know too well that in strict funding climates, basic research is increasingly undervalued—and we wouldn’t want to compound the problem within the arts. So how about this model advanced by the late political scientist Donald Stokes?

In his book Pasteur’s Quadrant: Basic Science and Technological Innovation, Stokes posited a category of research that marries a “quest for fundamental understanding” (read: basic research, or, in my thought experiment, basic art) with a “consideration for use” (strictly applied research or, again, art). Do we think there are certain “basic” arts projects that fall within the category of “use-inspired,” but where utility is not the primary motive?

Either way, it’s clear that by striving to integrate the arts and humanities with the sciences in higher education (not to mention lower levels), both the STEM and arts communities might be able to reach, together, a larger, more diverse student population than either can alone. Many STEM proponents agree that the arts and design can provide inroads to learners who might not come in through traditional curricula or teaching methods. Similarly, cultural policy-makers and funders have put a greater premium of late on reaching historically underserved communities, just as many arts organizations have sought to examine representation of these groups in their governance and programming. From this angle, arts integration in science learning could prove salutary for both fields.

My break is over, and I need to get back to the workshop. How does any of this relate to “global welfare,” to which I hinted in my opening paragraph? Based on testimony from many workshop participants so far, empathy is a competency that the arts and humanities might be particularly good at instilling in STEM learners. To confront perplexities at home and abroad—failures of anticipation, comprehension, and articulation—we would do well to think of the stakes as cultural no less than curricular.