Taking Note: Yeats and the Economics of Creativity

Last month, at the invitation of the U.S. Embassy in Dublin, I took part in a conference titled "Creative Minds: The Importance of the Creative Economy in the U.S.-Irish Relationship."

The brainchild of Ambassador Kevin O'Malley and his staff, the April 23 event in Dublin was one of a series being held to "strengthen the creative industry ties between the United States and Ireland," to quote the embassy website. Addressing Irish arts and cultural groups, design firms, intellectual property consultants, and multinationals with branches in Ireland (e.g., IBM, Intel, Disney), I reported findings from the U.S. Arts and Cultural Production Satellite Account, the NEA's joint research project with the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

I began my talk by professing admiration for Irish literature. Since college, for example, I've gone back repeatedly to the writings of W.B. Yeats (1865-1939). This testimony led to a conclusion that I played for a cheap laugh: despite the poet's versatile offerings, an extensive search shows he had surprisingly little to say about the "creative economy." (I should know, I told my audience; I had looked for a Yeats quote to drop into my PowerPoint.)

Caution: never underestimate a man who was not only a poet, but a playwright, theater manager, essayist, occultist, folklorist, anthologist, and two-term senator of the Irish Free State. From artifacts housed in the city of Dublin, it's clear he understood if not the creative economy, then the economics of creativity.

Here's what I mean. The day after the Creative Minds event, I toured the Abbey Theatre, where resident archivist Mairead Delaney showed me program brochures and meeting minutes from the earliest days of the venue. Yeats co-founded the Abbey in 1904. The archives tell that he and his colleagues were expert at fusing artistic and business practices.

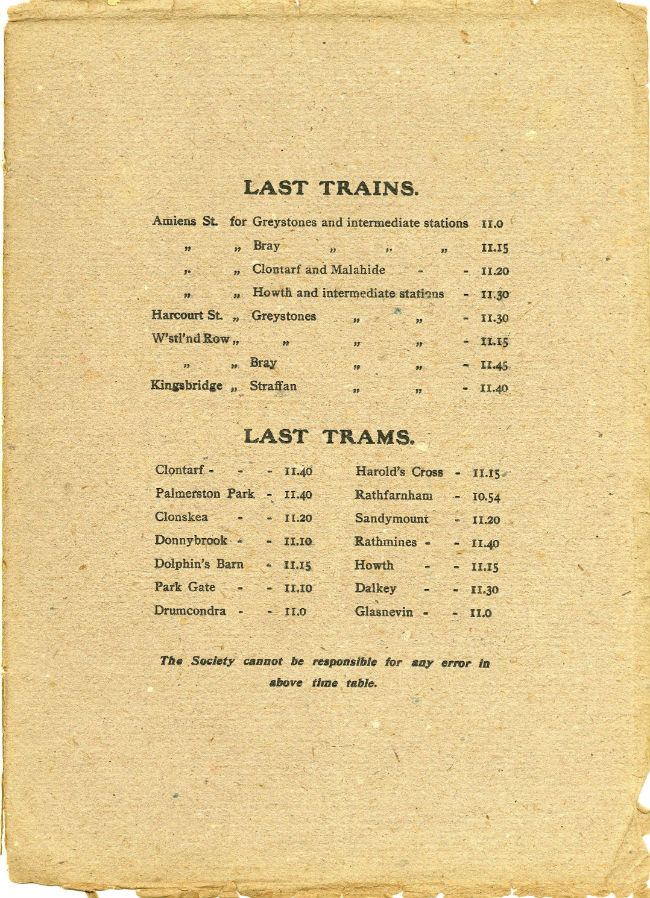

For example, the program for the theater's opening night reveals, on the back page, times for the "last trains" and "last trams" home. This simple device must have helped convince theater-goers that the Abbey catered to their personal needs, that it would be a hospitable place to spend future evenings.

Now consider how earlier this year, the NEA reported research highlighting "difficulty of getting to the location" as a chief barrier to adults' attendance at live performing arts events. It didn't take data to persuade Yeats and his friends that including train times would be a good idea.

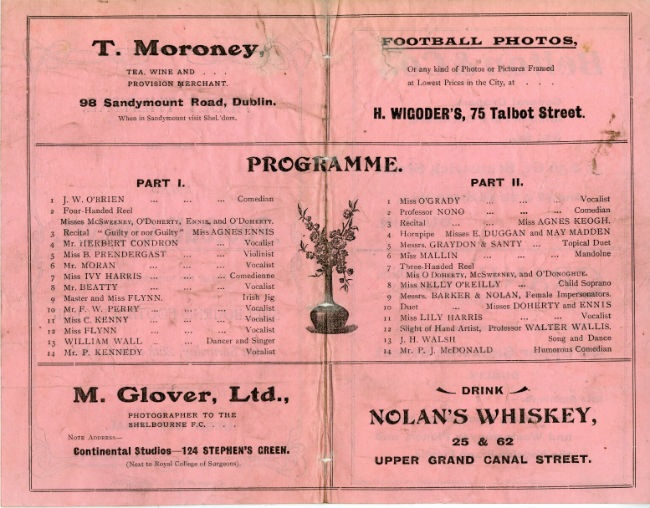

Similarly, NEA research has suggested affinities among arts and sports participants. Again, without the benefit of a government survey, Yeats' team decided to partner with the Shelbourne Football Club on the night of April 28, 1906, to hold a "Grand Football Concert" in celebration of the Irish Cup Final. Talk about cross-market synergies.

A program for the Grand Football Concert in 1906, organized by the Abbey Theatre. Photo courtesy of Mairead Delaney, Abbey Theatre

How he would have loathed the term! Reading only the poems, in fact, one might conclude that Yeats belittled the business side of all he did. He wrote: "The fascination of what's difficult/Has rent spontaneous joy and natural content/Out of my heart." Then, further on:

...My curse on plays That have to be set up in fifty ways, On the day's war with every knave and dolt, Theatre business, management of men.

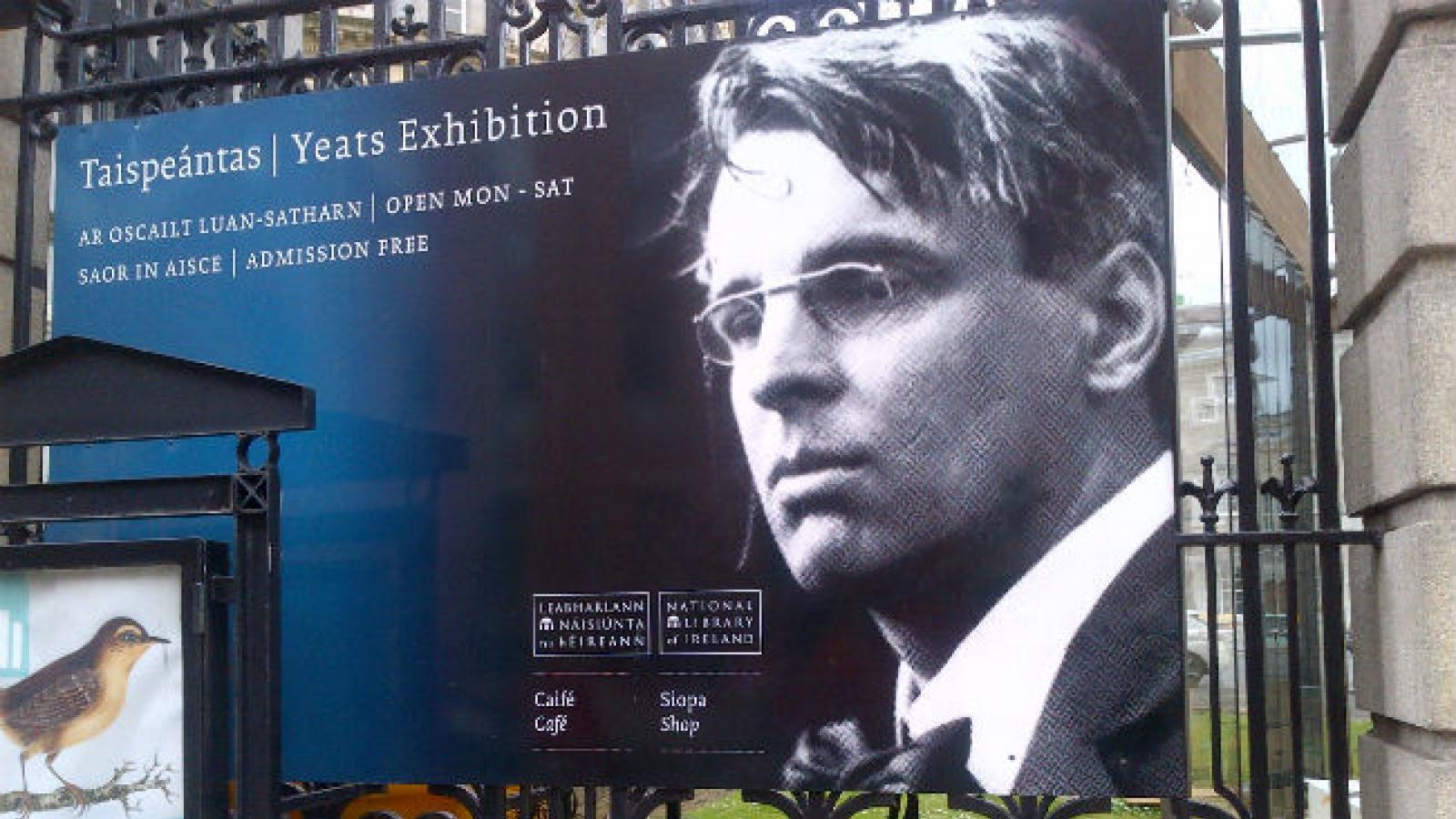

Despite his seeming distaste for the day-to-day transactions necessary to sustain his artistic enterprises, Yeats was eminently practical. After touring the Abbey, I looked into Dublin's National Library, where a state-of-the art, interactive exhibit shows Yeatsian memorabilia to mark 150 years since the poet’s birth. One find struck me, a government researcher in the arts, as monumental.

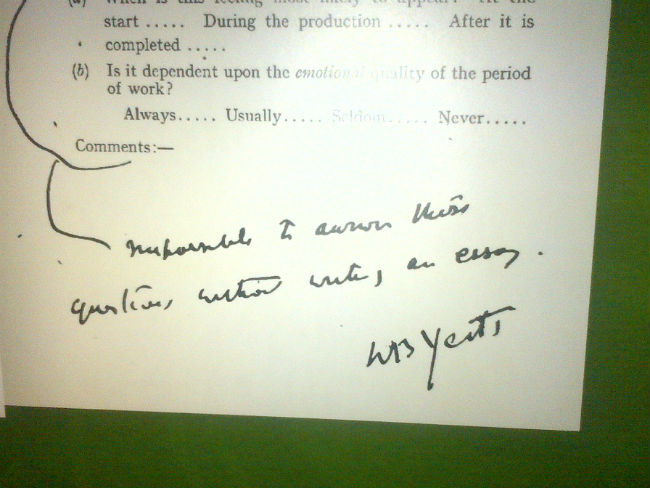

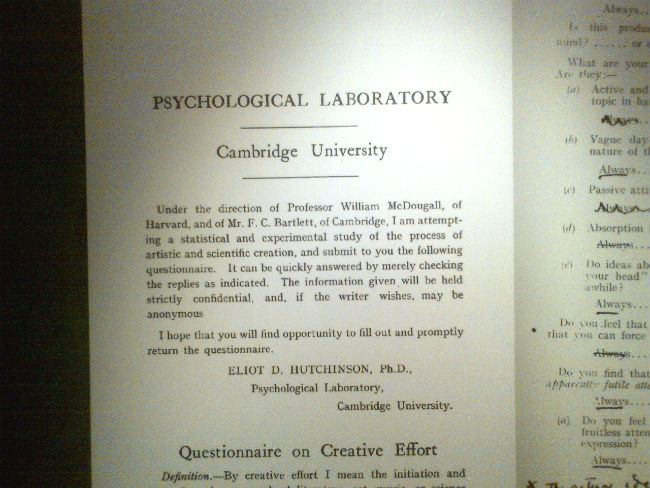

There, in a display case, hung a questionnaire Yeats answered for one Eliot D. Hutchinson, PhD, Cambridge University. Hutchison had sent Yeats a short survey for a "statistical and experimental study on the process of artistic and scientific creation."

In the survey, the results of which were never published, Yeats was asked, using a Likert scale (options: "Always," "Usually," "Sometimes," "Never"), a series of items about creativity.

It's an efficient little survey instrument. (Revealingly, Yeats checked "Always" when asked if he revised his work, and also if he worked "systematically regardless of inclination"). At some point, however, he must have felt that the questionnaire was maybe, well, too economical, because in response to the last section he scrawled: "Impossible to answer these questions without writing an essay."