Ten Years in the Making

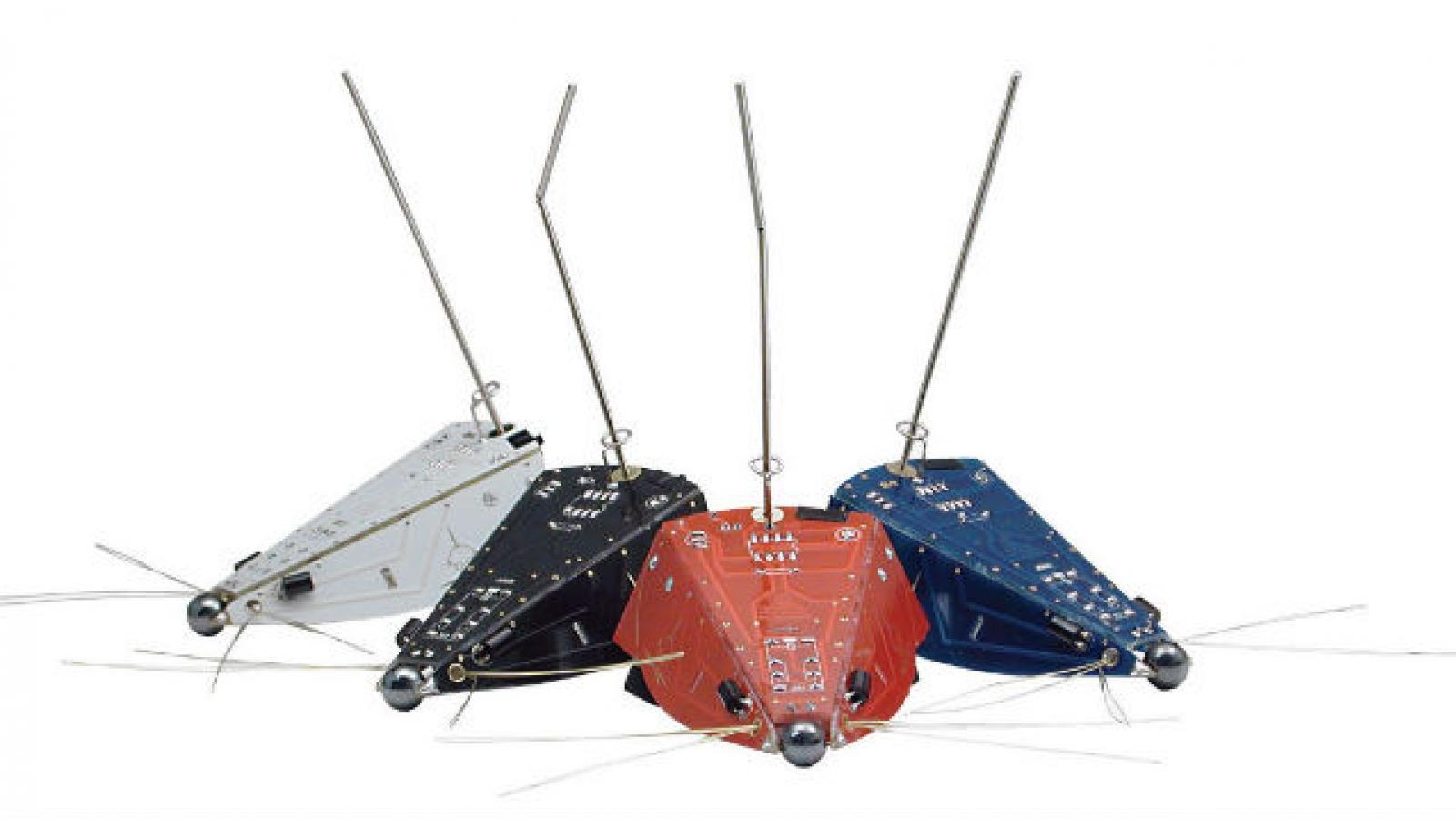

In an early maker project, Gareth Branwyn turned computer mice into light-seeking robots, which he called Mousey the Junkbot. Here, the Herbie circuit and Mousey the Junkbot mutate into the Herbie the Mousebot kit from Solarbotics. Image courtesy of Gareth Branwyn

I still remember the day that Mark Frauenfelder called me, in 2004, and asked me if I wanted to contribute to a new magazine that he was helping to launch, called Make:. He described it as “Martha Stewart for geeks” and as an updated 1950s-era Popular Science (Make: was originally digest-size and had a retro 50s vibe to its design). He asked if I had anything to contribute. I had what I thought was the perfect candidate. I had just published a book on hobby robotics (Absolute Beginner's Guide to Building Robots). In that book, I'd done a project, called Mousey the Junkbot, where I'd turned an old analog computer mouse into a light-seeking robot, using scavenged parts from the mouse itself and other junk-drawer electronics. That how-to would end up in Volume 02 of Make: and would become one of the magazine's early iconic projects (even ending up in a hilarious segment on the Colbert Report). A parts bundle was soon developed and sold by Make: and a robotics company, Solarbotics, eventually made a kit inspired by its design.

As soon as the first issue of Make: arrived on my doorstep, in February of 2005, I knew Mark, founder Dale Dougherty, and the others behind the magazine were truly on to something significant. It struck a resounding chord in me and I knew it would in many others.The subtitle of the magazine was “Technology on your time,” making it something of technology's answer to the slow food movement. Make: gave a unifying identity to weekend tinkerers, garage inventors, crafters, hobby enthusiasts, and all manner of do-it-yourselfers. All of these people could now identify as “makers” and see the common threads that bound together these diverse forms of working with your hands. The magazine gave an identity and a voice to a new kind of hands-on culture, one where people were no longer content with being passive consumers of technology. They wanted to understand how it worked, fix it themselves, improve upon it, and even design and build their own projects and products. Readers of Make: were encouraged to share their passions and clever creations, in the pages of the magazine, on the magazine's website, and in person, at the Maker Faire events which launched a year later, in 2006.

Gareth Branwyn turning computer mice into light-seeking robots at the 2007 Maker Faire Bay Area. Photo by Scott Beale

As Dale Dougherty likes to point out in his frequent and inspiring presentations about the maker movement, we are all makers at heart. Especially as Americans, whose collective backstory is steeped in tales of Yankee ingenuity, invention, and a sense of limitless possibility, we come from a root stock of makers. The maker movement is about leveraging our unique moment in history to create a new type of grassroots movement, with its powerful online collaboration and on-demand educational tools, readily available and relatively inexpensive high-tech components (tiny microcontroller computers, sensors, servomotors, wifi radios, etc), and emerging new fabrication technologies, like desktop 3D printers and computer-controlled cutting machines.

At Maker Faire Bay Area this May, I was talking to other presenters whose kids have also grown up at Maker Faire (my son has participated with me for the past nine years, ever since he was a teen). Our kids have gained a tremendous amount of confidence in their ability to figure things out for themselves and to leverage online communities and resources to get the help they need in undertaking whatever projects they fancy. They understand, as adult makers do, just how abundant those resources are and how eager various DIY communities are to assist those wanting to learn new things, to troubleshoot technical problems that arise, or just to share in the fruits of each other's making activities. This is a culture of enthusiasts that celebrates education, sharing, and collaboration. Returning to my original Mousey the Junkbot project, its evolution is perhaps symbolic of how the maker movement as a whole operates and how it has evolved. My little robot design was not entirely my own. The electronics I used, called the Herbie circuit, was originally designed by Randy Sargent, an MIT student who used it in a line-following robot (its little sensor eyes cast down to follow a black line on the floor). Robot builder and Solarbotics store owner, Dave Hrynkiw, had modified the circuit to be a light follower and included it in his 2002 book, Junkbots, Bugbots & Bots on Wheels. I found it there and decided to use a computer mouse case and parts scavenged from within to turn it into a robo-mouse complete with touch-sensor whiskers and a power switch for a tail. I also made some other improvements to the design. Based on the success of my project, Dave further refined the design and made a slick kit with a circuit board body that actually looked like a proper mouse. The mutant Herbie the Mousebot was born.This trajectory of project improvement, a spirit of openly sharing design ideas, online collaboration (Dave was also the tech editor for my robot book where Mousey made his first appearance), and eventual product development, is indicative of the maker movement in general. Ten years in and many makers are now “going pro.” Give people “permission to play,” give them powerful technologies, tools, and resources, and real innovation will result. The consumer 3D printer grew out of the maker movement. As did hobby drones. And the wildly successful Arduino microcontroller and Raspberry Pi single-chip computer which now power countless maker projects. There are these and countless other so-called open source hardware technologies—some now multimillion dollar businesses (billions in the case of 3D printing)—that all grew out of casual workshop tinkering.

Cover of Make: Volume 02 featuring Mousey the Junkbot. Image courtesy of Gareth Branwyn

If we came from a root stock of thinkers, doers, and makers—the people who founded this great nation, built its industries and infrastructure, led the world in manufacturing, science, and technology—sadly, we lost some of that STEAM along the way. The maker movement is helping us to reclaim that momentum. With the impressive distance traveled in only a decade, one can only imagine the promise of a new generation growing up with the problem solving, can-do, hands-on assumptions of the maker movement central to its worldview.

Want to find yourself feeling hopeful about the world and the daunting challenges it faces? Get thee to a Maker Faire. And then, think about rolling up your own sleeves and getting your hands dirty for a change. The future is not going to make itself!

Click here to see how the NEA is involved in this weekend's National Maker Faire.Gareth Branwyn is a freelancer writer and the former editorial director of Maker Media. He is the author or editor of over a dozen books on art, technology, DIY, and geek culture. He is currently a contributor for Boing Boing, Wink Books, and Wink Fun. His new best-of writing collection and “lazy man’s memoir” is called Borg Like Me.