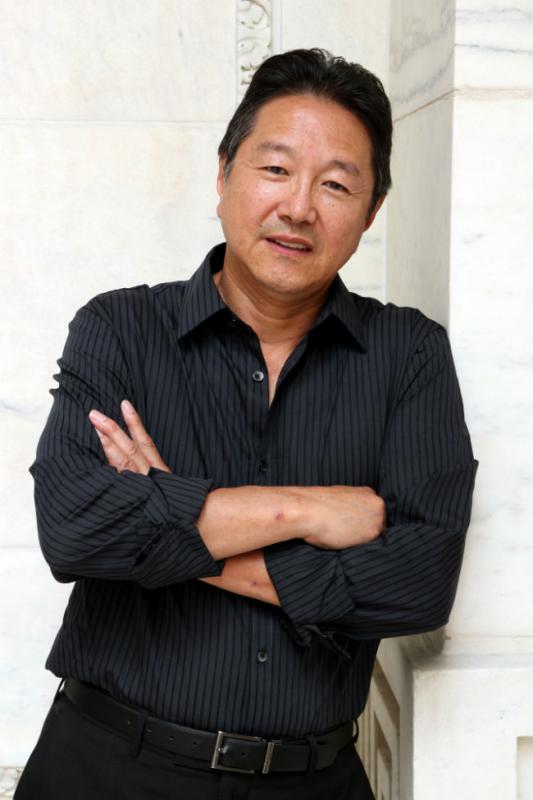

Art Talk with Playwright & Director Rick Shiomi

Growing up in Toronto, Rick Shiomi was acutely aware that he didn’t look like other children. His Japanese heritage felt incongruous in a city that was mostly white, and he was left with a feeling of wanting to escape.

But by the time he hit his late 20s, his identity began to feel less like a burden and more like a boon. After writing his first play Yellow Fever, he found that theater was the perfect medium to celebrate his background, and to bring together the community he once longed for. Once he moved to Minneapolis, he expanded his impact by co-founding Theater Mu in 1992, which interpreted the Asian-American experience for the stage. Later rebranded as Mu Performing Arts to incorporate Shiomi’s passion for taiko—a form of Japanese drumming—Mu has been a driving force in empowering Asian-American voices within Minnesota.

Shiomi has recently taken his mission a step further by co-founding Full Circle Theater Company, which is dedicated to producing multicultural, multiracial theater. We recently talked with the playwright, director, and community activist about his career and personal story, and heard his take on the state of theater today.

NEA: I know your parents were interned during World War II. How did that shape your sense of identity growing up?

RICK SHIOMI: As I looked at it after the fact, I can see that it had a huge impact. My family was actually based in Vancouver, and was very prominent in the Japanese community in Vancouver. My parents and family eventually were sent to the camps, and then they moved east to Toronto, where I grew up in a predominantly white and largely immigrant community. So I basically grew up not wanting to be Japanese-Canadian, because you just didn't fit into anything that seemed normal.

NEA: When did that start to change?

SHIOMI: I graduated from the University of Toronto, and left Toronto leaving a lost life behind in a way and feeling that I just wanted to get away from something. I went to Vancouver, I was there for a couple of years, and after that, I ended up traveling the world in two years. I went from Vancouver to Europe to Asia and then back to Vancouver. For me, that was quite a life-changing experience, seeing the whole world rather than one part of society in Toronto.

But I still wasn't thinking in terms of a Japanese-Canadian or Asian-Canadian or Asian-American concept at all. My first major involvement was helping to organize a community festival called the Powell Street Festival [which celebrates Japanese-Canadian arts and culture]. That festival, for me, was a huge awakening. I learned so much about Japanese-Canadian history. I realized at that point that all of my growing up in Toronto in a basically white society, was because of what happened in the camps in World War II. So even though I was myself never interned, I realized that my whole life had been hugely impacted by those events.

I had always wanted to write, and once I got involved in the Japanese-Canadian community and since then the larger Asian-Canadian, I started to find that I had something to write about. I ended up meeting some people in the Asian-American community in San Francisco, and they helped me write my first play, which was Yellow Fever. From there, I realized that theater was going to be my artistic world. It was one of those strange feelings where you finally realize you've come home to something. After the fact, I found out that my grandfather had run a kabuki-style theater in Vancouver around the turn of the 20th century, and that my uncle had done theater in the 1930s and even in the camps.

NEA: Can you describe the climate and reaction when you started Mu Performing Arts in Minneapolis?

SHIOMI: It was a dual reality in the early ‘90s. On the one hand, people were so unfamiliar with Asian-American theater here, that it was truly an oddity and people weren't sure what to make of us.

But the good aspect of it was that in the early ‘90s, the whole issue of diversity was starting to happen here in Minnesota. So the foundations and funding sources were very supportive of our company early on. They felt like we were bringing something new to this community—and something that the community needed. Beyond that, the quality of our work started to establish the company as significant in this theater community. We were continuing to get more and more funding because the work itself was establishing a certain level of reputation and recognition.

NEA: Speaking of diversity in theater, this is obviously still a major topic of discussion, especially with the recent success of Hamilton. What’s your take on the issue: what are we doing well and what could we be doing better?

SHIOMI: I think if I look at the Twin Cities as an example, I would say there's been tremendous development in terms of diversity in the last 20 years. I feel like you have to look at it in terms of 10 and 20 years rather than thinking, "In the next year or two, is it going to change significantly?" So I feel like there's been tremendous growth. Not only is Mu Performing Arts doing well, but Asian-American actors are starting to be cast in shows in many other companies. It's not that Asian Americans are now earning the biggest leading roles or anything like that, but their presence is there and I think it's growing.

In some ways, what we did here in Minnesota was highly unusual, in the sense that we created a company that was able to feed artists into the whole community. That made it possible for the concept of Asian-American theater and Asian-American artists to be considered part of the regular theater landscape. But in other cities, it's going to be hard to find any Asian-American actors. So it's not an even development. In some areas, there's been more progress, and in other areas, there are still major issues. In some areas, it's not even on people's radars.

I think some of the bigger issues in terms of diversity are specifically about Broadway and Hollywood, where it's more about money. There are major controversies going on at those levels. The Asian American Performers Action Coalition was doing an analysis of the number of the Asian-American actors on Broadway and it's really miniscule. Then of course there is always controversy over how Hollywood is casting white actors in what might have been Asian roles, or Asian roles that have been transferred into white roles. So on that level, there are some real challenges.

NEA: Dovetailing on that topic, can you tell me what the effect of Mu Performing Arts has been on the larger Minneapolis community?

SHIOMI: Within the Asian-American community, I think there's been a huge impact. Asian-American young people have a company that they can recognize. To a certain degree, that creates a certain legitimacy for their aspirations. There's a lot of pride about the work that Mu Performing Arts has done. There are many communities that have their own traditional performance forms. But those performance forms are largely ignored by the larger society. They happen within those communities. But what Mu was able to do was to create something that was representational of the Asian-American experience and get recognition for it in the mainstream theater community.

In the larger theater community, there's been a huge consciousness, awareness, and growth of Asian-American theater because of Mu Performing Arts.

NEA: You’ve been very involved with the Japanese community in both Canada and the U.S. Do you view your theater work as a type of community activism?

SHIOMI: Definitely. My theater work came out of my community activism, and became an extension of that activism. Being Asian American, there are so many hurdles to get across in terms of creating awareness and recognition of Asian-American theater, wherever you go. Those two are, for me, wedded together completely.

I now started a new company with my wife and three other artists called Full Circle Theater Company. We are focusing more upon diversity in a larger sense. So even though I've spent the last 30 or 40 years focusing on the Asian-American piece of it, this company is looking at the larger mix, and working with African-American, Latino, and Native-American theater artists.

NEA: Can you walk me through your creative process?

SHIOMI: The first half of my career was playwriting, and that creative process was again wedded to my social activism. Gradually, I've been moving more toward directing and seeing how as a director, you can begin to create interesting art but then wed that social activism to it anyway. At Mu Performing Arts, we ended up doing Into the Woods. It became a lot of fun because in that case, I imagined the whole musical happening through Asian folktales, not through European folktales. So the Cinderella story I set in Filipino culture. The baker and his wife I set in a Korean folktale culture. It was fun to do.

One of the biggest things I did in that world was I was approached by Skylight Opera Company. They wanted to do a collaboration on The Mikado, which has been very controversial in America in the last four or five years. When they approached me, I was a little surprised, because it's one of the things that Asian-American theater artists love to hate. But I realized that if I turned that opportunity down, they would likely do it in the same way it's always been done. So I thought: is there a way of doing this that starts to deal with or remove the Asian stereotypes that are so much associated with The Mikado? What I did was I reset it in Edwardian England. I changed some of the names, I adjusted some of the dialogue. We also cast Asian-American actors in it, which never happens. So we had this total inversion of The Mikado. But watching it was like a guilty pleasure, because you could enjoy the music, you could enjoy the cleverness, without having to worry about the stereotypes. So I felt like that opened a new door for me and that material.

NEA: You also perform taiko. Can you talk about the overlap between taiko and theater?

SHIOMI: In Vancouver when we were working on the Powell Street Festival, that group of people was in search of connection to traditional Japanese culture in a way that was exciting for us. We had the opportunity to be exposed to taiko through touring groups from Japan but also through taiko groups in California. So we started our own group in Vancouver. When we started Theater Mu in Minnesota, some of the actors in the company knew that I played taiko and they asked if I would teach them. To my surprise, they loved it, and then a whole aspect of the theater company became involved in taiko.

NEA: What do you think are the biggest challenges the Asian-American community has to overcome in theater?

SHIOMI: In theater itself, there has to be a more positive attitude toward the importance of representing the Asian-American community and culture. I feel like the Asian-American community itself has been slow to come to that support. In most Asian-American families, if a son or daughter says they want to be in theater, nobody's embracing them for that. And that's a problem. Because when you're discouraging those people at that age, it reduces the number of participants in the cultural life of the community.