Art Talk with Sabina Ott

A recent Guggenheim Fellowship winner, Sabina Ott has had her sculptures, paintings, and videos shown in over 100 exhibitions around the world. Her works are in museum collections from New York to California, and she has curated dozens of shows and taught hundreds of art students. And yet, one of her most notable projects takes place far from the conventional art world, on a quiet neighborhood street in Oak Park, Illinois, just outside Chicago.

Since 2011, Ott has run Terrain Exhibitions in her front yard, a unique, outdoor space where invited artists create site-specific installations. Ott hosts the openings—home-cooked food and all—turning her home and studio into a local creative nucleus. We spoke with Ott about Terrain, her love of literature, and her new exhibition who cares for the sky?, on view at the Hyde Park Art Center through May 1st.

NEA: In many ways, your artwork defies categorization. Where do you look for inspiration?

SABINA OTT: Something that has been consistent with me has been storytelling, and an investment in my material to carry that story. I began to work with encaustic, and started building up surfaces and working with graphic symbols. But it was the encaustic that was really the carrier of the meaning. I would carve away and pour, and that process would be very important to the metanarrative of my pieces.

I also started really looking at a lot of feminist theory in the '90s. I got very invested in Gertrude Stein as a writer. I used her consistently for 20 years as inspiration for my work. I try and use her methodology when I approach materials and things that I'm making, and I try to use a similar kind of sense of humor and an attachment to everyday objects and images that she also used. So there are methods that she employs as a writer that I try to employ as a visual artist.

NEA: You mentioned storytelling and narrative, and I certainly notice a strong overlap with literature in your work. Could you talk a bit about that relationship?

OTT: Both my parents worked, so I was taken every day after school to the library. The library was my babysitter. I would give myself the task of trying to read everything on the bottommost row of the children's library, and then I would work my way to the second level. I was reading constantly, indiscriminately. It gave me, I think, a deep internal life. I sink very easily into an empathetic state through my early exposure to literature. So I've always gone to that material because it's source material for how I live my life.

NEA: Tell me about Terrain, and how you decided to launch an exhibition space in your front yard.

OTT: When I moved to Chicago, I didn't really know anybody. I began to think about how can I really make this a place where I'm fed as an artist and as a person. I thought, “Okay. I need to have social interaction. I like to cook. I like to have people in my home, and I like to support other art that I like. I like making sure that the things I want to see are out there and able to be seen." So I started Terrain Exhibitions, which is a project space out in my front yard.

The goal of all the projects are to be seen by people walking on the street that are incidental viewers, not necessarily habitual art purists. It's all artist supported. I don't have any funds that I give them. They just want to make something really interesting in whatever way they can that intersects with architecture, the idea of home, suburbia, the city—whatever topic engages the site. For the openings, I get to cook. That's the personal part to—I want to feed people. Whether it's food or whether it's ideas or whether it's art, I want to be feeding people.

NEA: How do you think the very informal, homey nature of Terrain affects both the artist that present in your yard, as well as the audiences?

OTT: I think the artists are freed up and challenged. One of my favorite projects was by the artist JC Steinbrunner. He makes very precise drawings of folded paper and flat things. They're very formal and they're very representational. But for this project, he decided to get a series of mailboxes. He bought ten mailboxes. He put them all in the front yard and then he invited people to mail letters to Mailbox 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10. He set it up so that people were apt to send very personal letters, or some kind of personal revelation, or a drawing. Then people would walk by and take a letter out of the mailbox and put letters in the mailbox.

It took about half the show for those things to get going, but it was incredible. It became this really interactive thing with a form of communication that's almost obsolete. It was amazing, and it had nothing to do with JC's drawings or anything that he did before. He was strong enough as an artist to not feel that he had to make something that was a signature piece, and that he could just make something very site-specific and engaging.

Seeing people address these sites in very unique and individual ways has affected how I think of my work as well. It's true that there's an informality to it that encourages experimentation, and I have been trying to approach all of my exhibition opportunities in that way.

NEA: Terrain is obviously a hyper-local community space. But at the same time, you have pieces in the Met and the Whitney and the Corcoran. Is there a balance that you look for in terms of contributing to your local community and contributing to the broader cultural landscape?

OTT: Community is a really odd word to use in relation to me because I've moved all around the country. I feel very mobile, and it's only in Chicago that I've really been able to understand or develop a relationship to the word “local.” There’s an artistic community here in Chicago that's similar in intensity to what I experienced in L.A., where I lived for so many years, but there's an energy to it that's really unique to Chicago. There’s comradery amongst artists here and it’s not as competitive. I'm trying to take all these ideas about this Midwestern life and make them parallel and rub up against the idea of international art life.

A couple that I learned a great deal from relative to this is Michelle Grabner and Brad Killam doing The Suburban [a project space in their backyard]. They live down the street in Oak Park, and they they didn't think so much about local or not local. They literally showed international artists in their garage, and they did it long-term. It's displacing this idea of a gallery culture with this home culture in a way that there was a longevity to it. It was a commitment to where they lived.

The community aspect of is interesting too because each artist really brings their own gang to the openings. There are regulars that come all the time, but then each artist brings their own group. So it has the opportunity to really expand and cross-pollinate communities in ways that you would hope a regular party would do, but doesn't.

NEA: Tell me about your current exhibition.

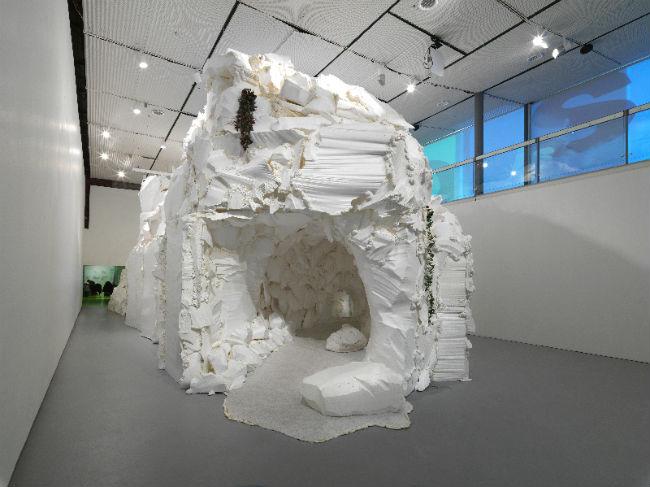

OTT: I have a show up now that actually is connected to Terrain in a way. It's very odd, and it's at the Hyde Park Art Center, which is a traditional, community-based art center. They invited me to what I do in this space, and I said, "I want to build a mountain." I wanted it to fill the entire space so that you didn't have a point of view; so that you had to come in and make a decision right away. "Am I going to go up the stairs to the top of the mountain? Am I going to go to the left or am I going to go to the right?"

It's all white and it's all Styrofoam and it's all gorgeous. It looks like a big floppy cake or something. There's a tunnel in it, and I invited all these artists to make work for the tunnel. I have about 100 pieces inside the tunnel, all fused to the Styrofoam. That's the only place where there's any color. I left everything else white, and the intensity is with other people's artwork in the tunnel. The whole thing is based on this story, The World is Round, by Gertrude Stein, which was her only children's book. It’s a beautiful book.

So the quote/unquote "community" is involved because they've donated work to the mountain. It's not an exact reflection of my hundred closest friends or something. A lot of it is people saying to me, "I want to do that," and I'm like, "Okay. Make a piece. Bring it over." They're people that I don't really know. So the boundaries are loose about what makes that community. And then, in the corniest way, that community is what supports this structure. That's what makes the mountain—all of these parts.

NEA: What’s your favorite thing about your art studio?

OTT: My first impulse is to say my books, because I have this amazing library. I look at them from a distance, and I go, "Wow, those are great books. I should really reread all of those books." And then of course I never do.

The second part is my dog, Alice, who comes with me everywhere. She stays with me all the time.

The other part I really love about it is it's my studio. It's in my backyard, and I don't have to worry about driving home or anything. I can stay there as long as I want. I can sleep there if I want. It's eight o'clock and I'll work until maybe 1:00 or 2:00 a.m. That's a good night.

NEA: What are the three artistic tools that you could not live without?

OTT: I really have to say my books. Also, I have people over to talk me through things. A lot of times, I have to talk through what I'm doing, especially if I'm working on a big project. And then, I couldn't do anything without spray foam. You know, when you go the hardware store and it says, "Fill gaps with foam in your plumbing?" It expands. That is the glue and it holds all my work together. I just want to wield my spray foam can. For me, it's so experiential. You just slap stuff together and then you don't know how it's going to come out. You spray it, and it turns into something else. I love that. I love that chance element of it a lot.

NEA: My last question is a fill-in-the-blank, and it is, "The arts matter because..."

OTT: For me, it matters because it's what I do. It's what I love to do. That's all. I'm really not interested in making things that teach a lesson. It allows me the most concentration and an almost meditative state of being, along with an engagement culture. So I get the best of both worlds: I can really concentrate and disappear into working, but at the same time, the work itself is a conversation with everybody else.