Fan Art and the NEA Big Read

You’ve just reached the end of your latest favorite book, the one you couldn’t put down, the one you raced through hoping all the while that it would go on and on. And now that it’s over, your first thought is: there should be more! But why wait on the author at her writing table, when those characters and their world are as alive for you as they are for her? You’ve got a pen, you’ve got a brush, you’re a creator: so you sit down to work.

As Bim Adewunmi wrote for Buzz Feed, the impulse behind fanfiction “is simple: If you love it, write (more of) it.” Much the same could be said for fanfiction’s sibling, fanart. Artists who love a book (or a tv series, movie, game, or any other kind of work) explore their favorite characters, relationships, scenes, and settings by making art about them. Often, what’s canon —i.e., elements officially belonging to the original story—are joined or supplanted by artist-generated elaborations and alternatives. So it should come as no surprise that in talking about their work, fanartists make frequent use of terms like “AU” (“Alternate Universe”), “headcanon” (defined on fanlore.org as “a fan's personal, idiosyncratic interpretation of canon”), and “fanon”(something not canon but nonetheless widely accepted among fans).

Fanwork has most often been associated with the genres of science fiction and fantasy, from Kirk/Spock slash fiction to the Harry Potter and Twilight works that come to mind for many millennials. Among titles in the NEA Big Read, Ursula K. Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea is a classic example of a book that has inspired its fair share of fanartists.

One of those is Elijah Lane, who publishes his art as maura-labingi on Tumblr—a hugely popular platform for fanwork of all types—and has made a number of images exploring the world of Earthsea. Discussing his art, Lane emphasizes the “intense emotional moments” that lead from reading to making art: “those [moments] are what bind me to a story and often what get drawn out by me in response. I did all of my Earthsea art over the course of a few months while I was reading the series and right in the thick of the emotion,” he noted.

For Lane, pushing the source material to new places is central to fanart’s appeal. As he explained, headcanons, fanons, and other fan-generated ideas “help flesh out worlds and characters beyond what we see from their creators and allow us to relate to them more.” When it comes to Earthsea, for instance, Lane (re)imagines the protagonist as asexual. “Being a part of the LGBTQIA community, coming up with something as seemingly small as ‘Sparrowhawk is asexual’ adds another layer of familiarity and love to the character that brings me closer and allows me to feel more,” he said.

When fans adopt—and adapt—a book or other work, they are adding their voices to a conversation that’s larger than any single piece of art. As Lane put it, “I was given the gift of creating by the creations of others.” Fanart refuses to discriminate between what’s “original” and what’s “derivative”; creativity is creativity. Period. And since that’s the case, it makes little sense to talk about fanart only in the context of fantasy, sci-fi, or any other single genre. Visual artists, as readers themselves, make art in response to all kinds of literary work, and the books of the NEA Big Read are no exception. In fact, following the Big Read titles leads to artists who might never call themselves fans, making art that they might never call fanart.

“I want to make art that is inventive and unexpected,” said California-based artist Edgar Hernandez, but fanart as a term for his work “feels a bit too limiting to me.” Instead, Hernandez describes Chac-Mool, which takes its name from the Carlos Fuentes story anthologized in Sun, Stone, and Shadows, as a piece rooted in the illustration process. In his words, an illustration is “an independent expression of the artist's experience with a story.” Explaining what inspired him to tackle Fuentes’s text in visual form, Hernandez added that “one of the things I love about illustration is that you can take your subject and interpret it however it seems fitting.”

In the case of Chac-Mool, Hernandez chose not to illustrate a particular scene from the story. Instead, he let one of its major themes—dominion—guide his own reshaping of the story’s elements. Asked about his painting’s debt to Fuentes, Hernandez offered a reminder that concurs with Elijah Lane: “It's worth saying that creativity depends on reading, listening, and watching other people's artwork and using it as fuel.”

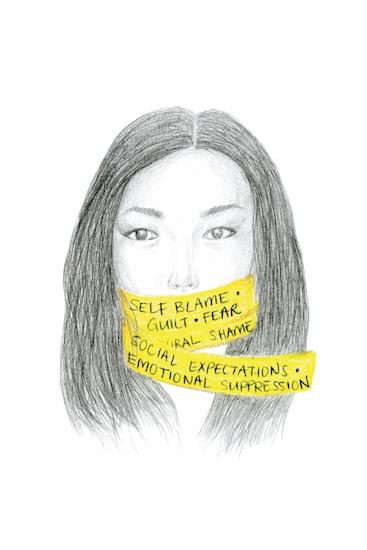

What fuels art is rarely straightforward or easily definable. But one lesson to take from fanart is that the connection between an artist and their fuel is often deeply personal. Felicia Liang, who drew Cultural Caution Tape after reading Celeste Ng’s Everything I Never Told You, writes about the novel that “the lack of communication within the Lee family was painful to read, but felt familiar.” Ng’s novel “brought back memories of my own upbringing, “ she said. “Many Asian American children weren't encouraged to be outspoken or to talk openly about their feelings. I was told I was too opinionated when I was younger, so I often bit my tongue instead of saying how I felt because of that.”

Liang, like Hernandez, doesn’t consider her work fanart. Similar to fanartists, however, Liang foregrounds concerns about representation when discussing her art. Driven by the lack of Asians and Asian Americans being represented in the media, Liang said she has “a special interest in using art and storytelling to raise awareness about Asian American culture and engage in conversations discussing race and identity.” To accomplish this, “I try to gear my works to connect with other Asian Americans, as well as share stories with those who had different upbringings,” she added.

Spurring such conversations is fundamental to Liang’s work as an artist. “I am an absolute believer in using art as a way to build community,” she said. Her “#100daysians” project, a series about growing up Asian American, encouraged friends and followers online to discuss themes like stereotypes, discrimination, history, childhood, and food, sharing their stories around her illustrations. Building community through art is equally important to fanartists, especially since fanart has been pioneered by and for marginalized groups who do not see themselves adequately—or ever—represented in the mainstream. Canon-defying fanworks are just one way for artists to fill in those gaps. Whatever else it is or may become, fanart speaks to people who cannot afford a passive stance if they want to see themselves, their ideas, and their experiences in the art that fuels their own creativity.